5-minute read

Dermot Feenan

LLB MA LLM Barrister-at-Law FRSA

.

What would you do if you reported an alleged offence to the police, were issued a receipt, and, weeks later, the police say they cannot find your report, and then do not respond to follow-up emails? This happened to me. I’ve now submitted a complaint. This blog sets out the background facts arising from an incident while cycling in England, sketches options for making a complaint, and explains why pursuing a complaint is important, not simply for personal reasons but also in the public interest.

Facts*

In February 2022, I used Hampshire Police’s online reporting system to report an incident affecting me while cycling, alleging that a driver of a car committed an offence under section 3 of the Road Traffic Act 1988.

* (Some details withheld pending any investigation.)

Hampshire Police, like many other police forces, encourage online reporting of incidents. I researched how other cyclists reported incidents, including through online reporting that allows video evidence of an incident to be uploaded – including in this article ‘What to do if you capture a near miss or close pass (or worse) on camera while cycling.’

My GoPro video camera, which I wear routinely while cycling, captured the entire incident. The video also captured a witness, who I later tracked down. He provided a witness statement. I included this evidence alongside my report of the incident.

I received an email confirming receipt of the report. It included this statement: ‘If you haven’t heard from us within six weeks it’s because we’re not able to take action. This may be due to a lack of evidence or an independent witness.’

Six weeks passed. No response. I phoned Hampshire Police and was put through to an officer (who I will anonymise as ‘Y’) in their Contact Management Centre, who couldn’t find any record of the report. We agreed that I would email my receipt of the report to Y.

I also agreed to send Y the screengrabs of the pages that I completed as I worked my way through the online submission, plus the video of the incident. Y gave a police email address. I agreed to include in the subject field that it was for Y’s attention. I sent the email.

I received a message that the email was undeliverable as ‘larger than the size limit for messages. Please make it smaller and try sending it again.’ I removed the video and re-sent the email. No reply. I sent two further emails over the next two weeks. Again, no reply.

Over two months have now passed since the incident was reported to the police. The report appears to have gone missing. Investigation has been delayed. Emails have gone unanswered. There’s been no follow-up. It’s not good enough. What would you do?

Making a complaint

Most of us don’t know about how to make complaints against the police. Less than 40% of the population know of the Independent Office for Police Conduct, set up in 2018 to oversee the system for handling complaints made against police forces in England and Wales.

Yet, the Policing and Crime Act 2017 and supporting regulations made significant changes to improve the police complaints and disciplinary systems.

The Independent Office for Police Conduct (IOPC) only investigates the most serious and sensitive matters, though; those that have the potential to affect public confidence in the police such as deaths and serious injuries. So, that doesn’t cover my complaint.

Complaints sent to the IOPC that are not the most serious and sensitive matters will be referred to the local police force. Police forces have local complaints procedures and personnel. Hampshire Police publishes their details online. A complaint can be submitted by phone, at a local station, online or by post to their Professional Standards Department.

In formal matters of this nature, I tend to prefer to send a complaint by letter with any accompanying documentation. In this case, I sent a three-page letter setting out the background facts and included in appendices to the letter copies of all communication to the police. I sent the letter by Royal Mail Signed For First Class delivery, which should arrive within one working day and provides a tracked record of delivery.

Even though the IOPC will only investigate the most serious and sensitive matters, it summarises what you can complain about generally. This includes complaints about how a police force is run, including policing standards and the service provided. If a complainant is dissatisfied with the outcome, a review may be requested.

Why it matters

Personal frustration and inconvenience aside, there are broader issues. An alleged crime isn’t investigated. Delay affects securing of evidence. A perpetrator may feel emboldened to offend again. Data on offences are lost, affecting policy and resourcing.

There are standards that seek to ensure proper collection and processing of information. The College of Policing states: ‘Collection, accurate assessment and timely analysis of information are essential to effective and efficient policing.’

There are also national standards on recording crime. The National Crime Recording Standards (NCRS) directs how statistics about notifiable offences are collected by police forces in England and Wales.

The NCRS vision is that ‘all police forces in England and Wales have the best crime recording system in the world: one that is consistently applied; delivers accurate statistics that are trusted by the public and puts the needs of victims at its core.’

Individual police services also have their own policies. Hampshire’s policy on crime and incident reporting requires recording of ‘notifiable crimes and incidents in an accurate, consistent and ethical way.’ Losing a report of an alleged offence doesn’t do that.

The disappearance of a report of an alleged offence can also undermine public confidence in policing. The public may no longer trust the police with information; as victims, witnesses or, even, perpetrators who consider confessing.

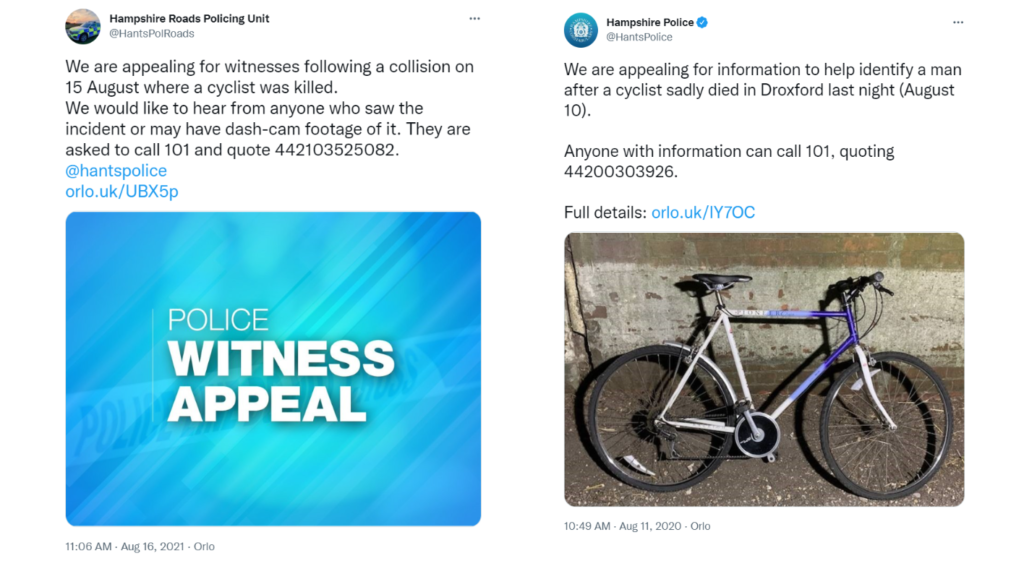

Hampshire Police regularly issue appeals for anyone with information about a crime to contact them (see illustrations below). When a report of an alleged offence goes missing, might this also lead to a drop in public responses to such appeals?

Some of the public already have no or low confidence in the police. Last month, the Local Democracy Reporter at Hampshire Live reported that people ‘have given up‘ reporting crimes in one of the areas covered by Hampshire Police.

A councillor on the Isle of Wight told a council meeting that residents were giving up reporting issues, especially online, because of a lack of police response.

Yet the Department for Transport is trying to encourage more people to cycle. Its policy Gear Change, launched in 2020, seeks to increase the number of people cycling in England. One of the themes in the policy is to protect cyclists.

Referring to cyclists as ‘vulnerable road users’, the policy recognised that they ‘fear being involved in collisions with other vehicles and seek higher levels of protection through the law.’ The government promised legal changes to protect cyclists.

The policy also noted ongoing consultation on updating the Highway Code to strengthen and improve road safety. Those updates were made in a new version of the Code, effective 29 January 2022. They include significant changes to protect cyclists.

Cyclists concerned about road safety may also wish to check their area’s Police and Crime Plan. Each Police and Crime Commissioner (PCC) is required under the Police Reform and Social Responsibility Act 2011 to produce a plan, which must set out, among other things, local police and crime objectives.

Hampshire’s PCC states that ‘[m]aking our roads safer is a priority for the roads policing teams’ and that road safety is one of the areas that she ‘will concentrate on with the police.’ A PCC also carries out reviews of police forces’ decisions on complaints.

The statistics on cycling casualties are concerning, so any complacency would be misplaced. In 2020, 141 cyclists were killed in Britain, whilst 4,215 were reported to be seriously injured and 11,938 slightly injured.

Regrettably, government cuts to funding the police have adversely affected policing, as recently acknowledged in the Final Report of the Strategic Review of Policing in England and Wales.

The impact has been especially acute in areas such as roads policing, where the spend fell by 34% in real terms between 2013 and 2019, compared to 6% for all police functions.

This decrease has led to a significant loss of traffic officers, whose numbers fell by 22% between 2010 and 2014 and by a further 18% between 2015 and 2019. Police traffic enforcement has dropped commensurately.

Cycling organisations are campaigning on road justice. Cycling UK, the country’s leading member-based organisation for cycling, says ‘the justice system fails to promote safety on our roads by not treating road crime as real crime.’

Cycling UK adds that ‘it is campaigning for a justice system that discourages bad driving, educates drivers to a higher standard, takes bad drivers off the roads, and delivers just and safe outcomes.’

In 2017, the All Party Parliamentary Group for Cycling & Walking inquiry Cycling and the Justice System urged that police should ensure that evidence of offences submitted by cyclists using cameras phones is used, and not ignored.

So, police losing a report of an alleged offence and not responding to follow-up emails is troubling. An offence under section 3 of the Road Traffic Act 1988 is, of course, relatively minor, certainly compared to more serious, especially indictable, offences, but it is still an offence and the police still have a duty to assess a report and, if indicated, investigate and take action against an offender. Where they fall seriously short of that, as here by apparently losing a report and not responding to follow up emails, they should be held accountable through a complaints system.

It would be hardly adequate to respond, as some might, that there’s no point, that a complaint about this matter loses the bigger picture of, say, corruption or misogyny in some police forces, or that the police are always bad. Such hopelessness, whataboutery or unfair criticism helps no-one, and certainly doesn’t serve the public interest. I have no automatic antipathy against the police.

There may be a reasonable explanation for what has happened with my report and follow-up emails. In any event, there should be an investigation, explanation, apology, and reassurance there’s a system that will retain and process the report and any future reports. If there isn’t, I can escalate the matter. This blog aims, in part, to help those who may be unaware of how to lodge a complaint about the police and to provide what might be publicly important information that could potentially lead to improvements in policing.

Last month the Home Affairs Select Committee in Parliament reviewed the role and remit of the IOPC, its first review on police conduct and complaints in nine years. While it acknowledged improvements, it also expressed concerns about:

- delays to investigations that detrimentally affect people’s lives

- complexity of language and processes

- inconsistency in updating and supporting officers and complainants during investigations.

I’ll be updating here on the outcome of my complaint.

____________________

@ Dermot Feenan 2022