5-minute read

Dermot Feenan

LLB MA LLM Barrister-at-Law FRSA

A recent article in The Economist on the recent shift in stance on race among Conservative MPs misunderstands what underpins the shift. It is not, as the article conveys, partly explicable in terms of an increase in BAME representation among MPs.

The article fails to recognise and analyse the place of race with reference to the ideological shift further to the right in the party, especially in Cabinet. The effect of this shift is reflected partly in different responses between Conservative and Labour MPs on 3 key issues.

These 3 issues are set out in research commissioned by The Economist on MPs’ views on:

- equality of opportunity to succeed professionally,

- whether government should do more to tackle racism, and

- whether (Black Lives Matter) BLM protests were justified.

Conservative MPs are approximately five times more likely than Labour MPs to believe that non-white people have the same opportunities to succeed professionally. Labour MPs are almost five times more likely their Tory counterparts to think BLM protests were justified.

Labour MPs were almost seven times more likely than Tory MPs to think that government should do more to tackle racism. Looked at another way, just over a third of Conservative MPs believed government should do more.

These substantial differences between Conservatives and Labour are symptoms of the ideological shift. The findings don’t explain themselves. Since The Economist article doesn’t provide a valid explanation, here’s a brief attempt at such explanation.

Shift further along the right

Over the last 5 years that shift further along the right was boosted when David Cameron opted to hold a referendum on whether or not the UK should stay in the EU.

Following the vote to leave the EU, that shift accelerated under the new leader Theresa May after June 2016.

Boris Johnson’s victory in the leadership contest in July 2019, and the consolidation of his power through the party’s landslide gains in the general election in December 2019, has led to the most right-wing cabinet since the 1980s.

Former Conservative MP Nick Boles tweeted after Johnson’s first Cabinet appointments: ‘The hard right has taken over the Conservative Party. Thatcherites, libertarians and No Deal Brexiters control it top to bottom.’

Four of the five authors of the free-market book Britannia Unchained now sit in Cabinet (Patel, Raab, Truss and Kwarteng). The book advocates fewer employment protections for workers and calls for an end to ’irrelevant debates’ about ‘women and men’.

But why would a shift further to the right entail a shift in the party’s stance on race? Part of that shift has also involved co-opting far-right voters on matters of race, directly and indirectly. This is evident in Johnson’s Islamophobic references to Muslim women as ‘letterboxes’.

In the wake of those and similar comments by Johnson in the run up to the 2019 general election, more than 5,000 supporters of a far-right extremist group, Britain First, joined the Conservative Party.

That co-opting is evident in Priti Patel’s attacks on illegal migrants. That shift to the right on race was evident in my research on an increase in anti-Irish racism by some Conservatives following the referendum on the EU.

The shift involves an attempt by the Government to dilute the momentum of Black Lives Matter (BLM), which has advocated radical change that addresses systemic racism and the legacy of historic slavery, by setting up the Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities.

Concerns have been raised about the role of Munira Mirza, head of the No 10 policy unit, in setting up the Commission. She has described a ‘grievance culture’ within the anti-racist field and argued that institutional racism is ‘a perception more than a reality’.

Concerns have also been raised about the appointment of Tony Sewell as chair of the Commission. Campaigners The Monitoring Group have notified the government of their intention to challenge the appointment through judicial review.

The organisation refers to what it says is Sewell’s ‘longstanding record of public statements rejecting or minimising the overwhelming evidence that already exists about issues such as institutional racism.’ The appointment of Sewell has been criticised by others.

The Commission also comprises Mercy Muroki, a student, who has written in a similar vein to Mirza and Sewell. The title of an article she wrote for The Times is indicative: ‘Disadvantaged kids are held back by the politics of class and victimhood’.

Her appointment to the Commission has received little attention in the media, but the inclusion of a very young, relatively inexperienced Black women is indicative of how a certain type of person and an ideological approach to race is being deployed on the right.

Muroki, who is a Conservative, wrote in The Times that her party is the only one on the side of meritocracy. She claimed that the Conservatives’ message is clear: ‘with some aspiration and grit, you too have the opportunity to succeed’. These claims are unconvincing.

Writing in September 2019, Muroki echoed Theresa May’s commitment in 2016 to a ‘Great Meritocracy’, which was repeated in the Party’s 2017 election manifesto, and was supported by commentators, such as, Paul Maginnis in his book The Return of Meritocracy.

The fact that ‘Great Meritocracy’ needed to be repeated 7 times (with capital letters) in the manifesto perhaps says something about the difficulty in making the case in the Conservative Party.

The ideology of merit-based advancement based on aspiration and grit has been thoroughly critiqued by those of unquestionably more ability than Muroki. They include Michael Young, who coined the term ‘meritocracy’, in his 1958 book The Rise of the Meritocracy.

Others have also exposed the assumptions, errors and costs in the type of merit argument embraced by Muroki, including Professor Jo Littler in Against Meritocracy: Culture, Power and Myths of Mobility, and, most recently, Professor Michael J. Sandel in The Tyranny of Merit.

Muroki criticises the Left in florid hyperbolic terms as ‘the merchants of victimhood’ whose ‘ideology is one of green-eyed finger-pointing and despair-mongering’. Again, the smear ‘ideology’. But also note the framing of the Left’s concerns as peddling victimhood.

Smears of ‘victimhood’ have become part of the weaponry used by Conservatives against the Left, illustrated in Daniel Hannan’s attack on the ‘passive-aggressive victimhood’ of students.

It is evident, too, in Boris Johnson’s statement in announcing the commission on race that he wished to ‘change the narrative’ on race. Johnson went on to say he wanted to ‘stop the sense of victimisation and discrimination.’

This rejection, denial, or downplaying of racism by the Government flies in the face of the fact that, as Bridget Byrne and others reported earlier this year, ‘racial and ethnic inequality, discrimination and racism remain entrenched features’ in Britain.

These features are found across immigration, criminal justice, health care, education, the labour market, housing, politics, and in the arts and media.

Attacking Critical Race Theory

The lack of political acuity and analysis in The Economist article extends to treating Critical Race Theory (CRT) – the concept recently attacked by Equalities Minister, Kemi Badenoch – as if it were simply American cargo freighted across the Atlantic.

Describing CRT as having ‘crossed the Atlantic’ shows an ignorance of how intellectual ideas circulate, including through the agency of academics resident outside of America in how they encounter, research and adopt insights from elsewhere.

Students and academics visiting universities in the US throughout the 1990s and into the millennium will have had the opportunity to acquaint themselves with CRT. The Conservatives’ attacks on CRT reflect an ethno-national, ideophobia of ‘foreign’ ideas.

This is reflected also in an unwillingness to recognise that notwithstanding differences between the origins of BLM in the US and its adoption in the UK, there are important convergences (as there are with BLM protests elsewhere).

This ideophobia incorporates an element of anti-intellectualism that has increasingly surfaced in some parts of the Conservative Party and which also characterises hard-right authoritarian regimes in, for instance, Hungary, Brazil, and the US.

The importance of ideology

The inaccuracies and lack of rigour in The Economist article matter. They matter because the ideological approach of the Conservatives affects different policies and laws. They matter because such ideology affects the conduct of officials.

This, in turn, affects real people. These laws, policies and behaviours are evident, for instance, in a hostile environment for certain populations such as refugees and those disproportionately affected by Covid-19.

The Economist article refers to differences between the parties ‘views’ on race but doesn’t identify, still less analyse, these differences as part of broader ideological shifts.

They matter because The Economist’s framing of the Conservative Party’s stance as one of mere ‘views’ hides the role and power of ideology. The creation and development of ideology is evidenced in books such as Britannia Unchained.

The ideology informs the work of numerous right-wing think tanks (many of which might be better described as lobby groups), such as The Henry Jackson Society, the Adam Smith Institute, and Policy Exchange.

Perhaps the difficulty for The Economist is in understanding the concept of ideology. There are diverse definitions, as noted in David Hawkes’ aptly named book Ideology. I have drawn from various approaches to develop the following working framework.

Ideology: a pervasive normativity of ideas and concepts held by people or institutions (such as government) that is intended to sustain, typically by concealing, relations of social power.

The ideas and concepts – not mere ‘views’ – are pervasive. They are not fleeting. They extend widely. Their character is reflected in the fact they take the form of norms; standards governing behaviour. They are intended to sustain relations of social power.

These relations are ultimately political, essential to governance. Though the concept of ideology fell out of favour largely because it cannot fully explain all forms of governance, it remains useful for understanding some political ideas and concepts.

It drives policy and law. Yet, the power of ideology is often achieved by making its operation invisible. The accusation from some Conservatives that their opponents are ideological casts out, or projects, onto others the very thing that animates conservatism.

This move seeks to undermine, denigrate or destroy the other’s ideas or concepts. This tactic is evident in Kemi Badenoch’s description during the Black History Month debate in Parliament of CRT as ‘an ideology’ (her only reference in the Chamber to ideology).

Badenoch said, ‘I want to speak about a dangerous trend in race relations that has come far too close to home in my life, which is the promotion of critical race theory, an ideology that sees my blackness as victimhood and their whiteness as oppression. I want to be absolutely clear that the Government stand unequivocally against critical race theory.’

CRT is, as its name conveys, a ‘theory’. The Economist generously describes it as a ‘discipline’, though that perhaps accords it a formality, a fitting-in with official classifications, that many CRT scholars would reject.

Retreating from analysis of racism

The smear of ‘ideology’ disables attempts to fully understand concepts such as racism. This is linked to denial of structural racism, institutional racism, racial injustice, and white privilege. Those problems require deep, long-term analysis.

They would also require mobilisation of the resources of the state, which is anathema to those committed to a de-regulated, free-trade marketplace.

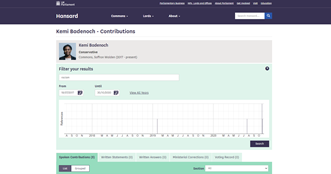

It is unsurprising that even the concept of racism itself is being shed by some Conservatives. This is evident in the contributions of Kemi Badenoch in Parliament. Since she made her maiden speech on 19 July 2017, Badenoch has mentioned racism only 5 times.

Badenoch was appointed Parliamentary Under Secretary of State (Minister for Equalities) in the Government Equalities Office on 14 February 2020. Between then and Friday, 30 October 2020, she has mentioned racism four times in the House of Commons.

Those mentions are materially different in substance to the references to racism by her opposition counterpart Marsha De Cordova (appointed 4 April 2020, to replace Dawn Butler), who has made seven such references.

De Cordova referred in her contribution to the debate on Black History Month to racism as a ‘systemic problem’. She also referred to ‘racism and discrimination’, ‘institutional racism’, and ‘structural racism’.

In a debate on Covid-19, she referred to a report on Covid-19 and BAME groups, saying that it ‘highlights yet more evidence that socioeconomic inequalities, racism and discrimination are root causes of BAME communities being disproportionately harmed by Covid-19.’

Badenoch, by contrast, denies or deflects from institutional or systemic racism. On 22 October 2020, she responded to a question from another Conservative MP noting that the first 26 doctors in the NHS to die of Covid-19, 25 were from minority ethnic backgrounds.

In a brief reply, Badenoch introduced the concept of ‘systemic racism’ in order to conclude that ‘the findings [from research] were that systemic racism did not explain that.’

She proceeded: ‘Systemic racism also does not explain the differences between groups, such as black Africans and black Caribbeans. If it was systemic racism, we would expect the figures to match and they do not.’

In the debate on Black History Month on 20 October 2020, she said that she had lessons for one of the other Black MPs in the Chamber, Dawn Butler: ‘Lesson No. 2: black history is not the history of institutional racism.’

Following the announcement that Tony Sewell would chair the Commission, De Cordova noted that Sewell had stated: ‘Much of the supposed evidence of institutional racism is flimsy’.

She asked Badenoch what assurances she would give that the Government are serious about ending institutional racism. Badenoch responded by saying, ‘It is important to clarify that Dr Sewell who chairs the commission has not denied that structural racism exists.’

This was not the issue which De Cordova raised. In any event, institutional and structural racism are different concepts. Not answering the question and instead setting up a straw man, appears to be one of the ways Badenoch refuses to engage on issues of racism.

Liz Fekete, Director of the Institute of Race Relations, writes that this denial it is ‘hardwired into the government’s way of thinking on race […] To put it simply, institutional racism today is held in place by policies, institutions and government spokespeople that deny it exists at all’.

These shifts in the Conservatives’ approach to race clearly reflect some element of electoral manoeuvring to gain far-right voters, for instance to protect the party’s majority government in the face of electoral gains by UKIP.

It should not be forgotten that law and policy on race also owes much to an infrastructure of protections threatened by Conservatives’ attacks on human rights.

As Mr Justice Tugendhat remarks, the Conservative Party regards human rights as a ‘foreign’ imposition from Europe. This is aside from the distinction between the European Convention on Human Rights and EU law.

With the end of the EU transition period on 31 December 2020 and accompanying cessation of EU law across all policy issues, it’s likely this ideological shift on race will extend – with even greater significance.

©Dermot Feenan 2020