20-minute read

Dermot Feenan

LLB MA LLM Barrister-at-Law FRSA

Concerns have been raised in the United Kingdom about the approach of some police in interpreting and applying new laws regarding the novel coronavirus. In particular, concerns remain regarding the position of one Chief Constable, Nick Adderley, of Northamptonshire Police, following comments he made during a press briefing on 9 April about setting up roadblocks and checks of shopping baskets and trolleys as part of his Force’s response to the spread of the virus and its disease, Covid-19.

Northamptonshire Police, shortened to Northants Police, is one of the smaller constabularies in England. It serves the county of Northamptonshire, with a population of around 748,000. The county lies in the East Midlands, equidistant from London to the south and Nottingham to the north. There are no cities in the county. The largest population centre is the county town, Northampton.

The area has one of the lowest numbers of total recorded crime, including public order offences and miscellaneous crimes against society, in the country.

Northamptonshire seems less likely than London or areas with national parks such as the Peak District to have residents or visitors engaging in violations of the law and guidance on movement during Covid-19. So, the Chief Constable’s comments seemed especially concerning.

Those comments may be understood in part with reference to the unprecedented powers granted by law to the police as a result of the coronavirus pandemic and the overreach by some police in interpreting and applying those powers.

In this brief article, I set out the Chief Constable’s comments. I discuss these with reference to law and guidance, explaining why the comments were wrong in law and inconsistent with guidance. I note problems with the Chief Constable’s subsequent responses to concerns about those comments, including with reference to police accountability and the convention on policing by consent. I elaborate these concerns through examples of heavy-handed policing elsewhere during the time of Covid-19 in the United Kingdom. Given the ongoing concerns with the Chief Constable’s comments, not least, as the UK government announced on Thursday, 16 April that it would extend its restrictive measures for a further three weeks, I also identify concerns about the oversight of the Chief Constable by the Northamptonshire Police, Fire and Crime Commissioner. These concerns have also been separately brought to the attention of the Police, Fire and Crime Panel of Northamptonshire County Council and the media.

The press briefing

On Thursday, 9 April, in the run-up to the Easter Bank Holiday weekend, Chief Constable Adderley said at an early-morning press briefing that police will “marshall supermarkets” and check shoppers’ “baskets and trolleys” to see whether they contain a “legitimate and necessary item” if people do not heed his “warnings”. The full excerpt of what he said is set out below. A video of the entire press briefing is available on YouTube.

“we will not at this stage be setting up roadblocks. We will not at this stage be starting to marshall supermarkets and checking the items in baskets and trolleys to see whether it’s a legitimate and necessary item. But, again, be under no illusion, if people do not heed the warnings and the pleas that I’m making today we will start to do that.” [3:12—3:48 mins, emphasis added]

The briefing was published on Northamptonshire Police website at 8.48 a.m. The Guardian covered it at 9.34 a.m. Northamptonshire Police released a video of the briefing via Twitter at 9.42 a.m., and via Facebook at 10.45 a.m. The briefing was also broadcast by Sky News.

There is in fact no power in any law pertaining to the coronavirus in the United Kingdom which allows police officers to set up roadblocks or to search baskets or trolleys. The principal law on restrictions on movement is set out, for England – the police force area in which Northamptonshire is located – in The Health Protection (Coronavirus, Restrictions) (England) Regulations 2020.

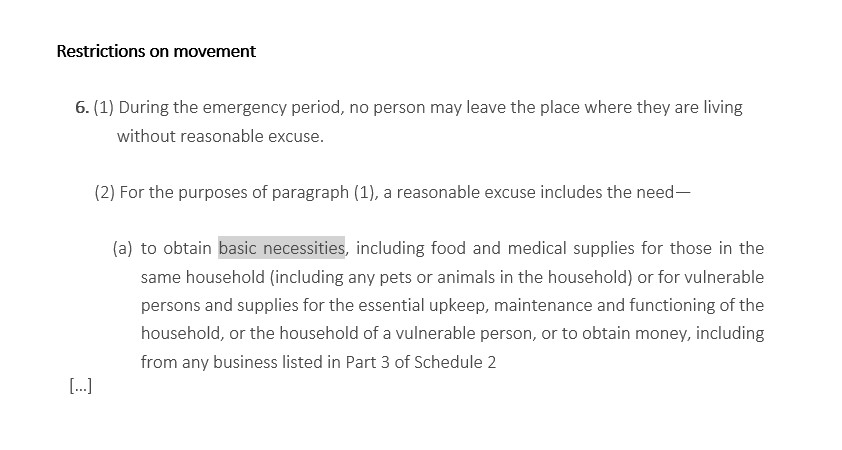

The Regulations restrict members of the public leaving the place where they are living without reasonable excuse. The Regulations set out a non-exhaustive list of thirteen reasonable excuses, including the need to obtain basic necessities. The Regulations do not define ‘basic necessities’. Rather, Regulation 6 (below) sets out non-exhaustive examples such as “food and medical supplies […] and supplies for the essential upkeep, maintenance and functioning of the household”.

As Tom Hickman QC, Professor of Public Law at King’s College London, points out in a note on the Regulations:

‘What this provision means is that food (and drink), is to be regarded as a basic necessity and therefore people can leave their home to go and buy it. It does not mean that one can only buy food and drink that constitutes a basic necessity or even that one can only leave home if one sets out to purchase at least one “basic necessity” food or drink item.’

This restrictions on movement do not apply to homeless persons (Regulation 6(4)).

Regulation 8(8) of the Regulations provides that the power of enforcement may only be exercised regarding movement where it is “a necessary and proportionate means of ensuring compliance with the requirement”.

Neither roadblocks nor searches of baskets/ trolleys would, in any event, be necessary and proportionate means of ensuring compliance with the requirement. First, no official evidence is available or was tendered of significant disregard of the law and guidance on shopping such as to frustrate the governing legislation, which is the Public Health (Control of Disease) Act 1984. Secondly, even if there was some anecdotal or informal local evidence that some people were disregarding law and guidance, a proportionate intervention might have been to more clearly inform members of the public on the content of Regulation 6(2).

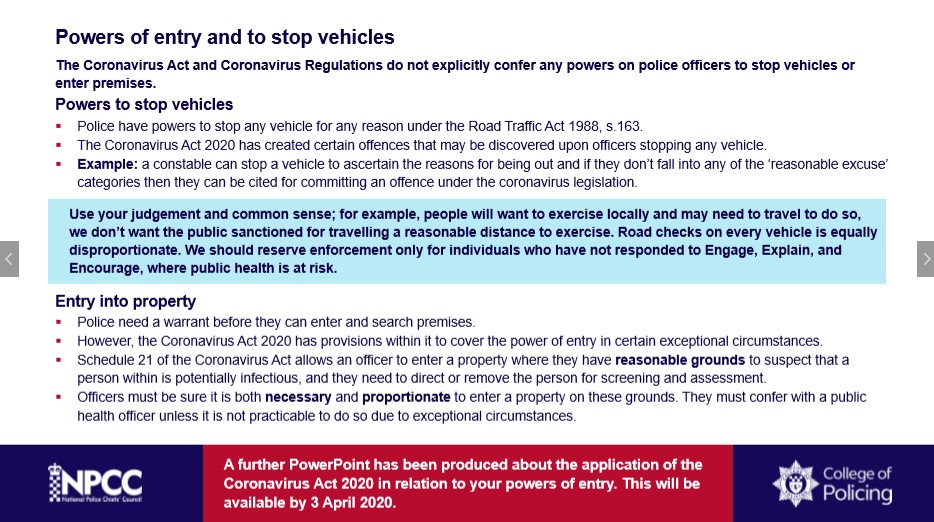

Moreover, the College of Policing guidance COVID-19-Policing brief in response to Coronavirus Government Legislation, issued 31 March, does not refer to roadblocks or shopping searches. A ‘roadblock’ is an extreme method of policing in a public health matter. It suggests blocking of a road, staffed by police. It sends out an entirely different message to a ‘road check’. The fact that Chief Constable Adderley used the term ‘roadblock’ is a matter of concern. The College of Policing guidance states that “road checks on every vehicle” is “disproportionate”.

Police roadblocks and searches of baskets and trolleys in such circumstances as were outlined by Chief Constable Adderley are also arguably in violation of Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights – incorporated into the law of the United Kingdom by the Human Rights Act 1998.

Article 8 provides: “Everyone has the right to respect for his private and family life, his home and his correspondence.” Searching a person’s shopping basket or trolley would likely be covered be the scope of privacy protected in Article 8. Restriction on the right must be legitimate, necessary, and proportionate. In McLeod v UK (1998), the European Court of Human Rights found that police officers’ entry into a home in which applicant was not present, where was little or no risk of disorder or crime, was disproportionate to the legitimate aim pursued and was therefore a violation of Article 8. In Gillan and Quinton v UK (2010), the European Court of Human Rights found that the stopping and searching of a person in a public place without reasonable suspicion of wrongdoing was a violation of Article 8 as the powers were not sufficiently circumscribed and contained inadequate legal safeguards to be in accordance with the law. Any purported authority to search baskets or trolleys would almost certainly fail to show that they were based on power sufficiently circumscribed and that they provided adequate safeguards to be in accordance with law.

Government Guidance issued on 29 March 2020 confirmed that shopping for basic necessities was an exception to the general principle to stay at home.

Notwithstanding, at 11.05 a.m. on 9 April, just a few hours after Chief Constable Adderley’s press briefing, the Office of the Police, Fire and Crime Commissioner posted a tweet stating that the Commissioner, Stephen Mold, was “confident” that the Chief Constable was “taking a sensible approach to enforcement of Covid 19 regulations” (see below).

Chief Constable Adderley retweeted that statement from the Office of the Police, Fire and Crime Commissioner.

Criticism builds

Elsewhere, the Chief Constable’s comments were attracting criticism. David Allen Green, a lawyer who has written on human rights and policing during Covid-19, tweeted in response to news of the Chief Constable’s comments via the Daily Mirror newspaper: “Good grief”; adding, “Tried to warn of what would happen.”

The Chief Constable’s comments continued to receive widespread criticism in the media.

The comments were covered in the Daily Mirror online at 10.03 a.m., details of which the paper tweeted at 10.04 a.m.

As the morning progressed, criticisms of the Chief Constable’s comments mounted.

Professor Matthew Cobb, Professor of Zoology at the University of Manchester tweeted, with reference to Chief Constable Adderley’s comments about searching shopping trolleys, that the police will create a public order crisis out of a public health emergency.

A search of Twitter using the words ‘police’ and ‘shopping’ on and from 9 April through the bank holiday on Monday, 13 April, shows hundreds of criticisms of Chief Constable Adderley’s comments.

The earliest criticisms should have been noted by Northamptonshire Police. Chief Constable Adderley was also aware of some them within hours of his briefing.

Chief Constable Adderley’s responses

Chief Constable Adderley issued a series of statements via Twitter throughout the rest of the day which cannot have allayed concerns about this authority.

At 11.46 a.m., he stated:

His explanation was certainly not conveyed in his press briefing that morning. Adderley’s subsequent tweet suggested an unwillingness to: (1) acknowledge that he had been wrong, (2) correct his statement with reference to law and guidance, and (3) to offer an apology.

As noon approached, more of the media picked up on Adderley’s comments at the briefing, with The Daily Telegraph posting at 11.52 a.m.

As further criticism mounted, Adderley sent another series of tweets.

At 12.08 p.m.:

Adderley then retweeted a post by ‘Sarah’ which stated “Look past the tabloid headlines for some balance…” That post retweeted Adderley’s tweet of 11.46 a.m. Adderley’s retweet of Sarah’s post implied that the ‘tabloids’ had got it wrong.

At 12.42 p.m., Adderley replied to a tweet in which someone asked whether hot cross buns were essential. He said, “we won’t search trolleys, a clear directive has been given that we won’t carry out roadblocks or decide what is a necessary item or not. The point I made was around the purpose of the journey, not what you’re buying..”

Two minutes later, Adderley responded to another tweet challenging the Chief Constable’s authority to instruct officers to search baskets and trolleys. Adderley posted: “read the clarification tweets… it’s about the journey, not your items…”

Again, the Chief Constable’s statement “[t]he point I made” serves to ignore the previous statement and seeks to position himself as entirely consistent. The maintenance of this view, rather than a clear acknowledgement that the previous statement was, at best, confusing, and worst, inaccurate is disturbing. It suggests an arrogance; an unwillingness to apologise for an error, show appropriate self-awareness, and seek to properly put right that error.

At 1.36 p.m., Adderley tweeted the Sky News tweet including a clip from an interview with Adam Boulton, Sky News, after the press briefing. His tweet stated: “We will not be searching trolleys or baskets and will not be carrying out roadblocks. The vast majority of the public are abiding by the law and we ask and urge the same from all. Working with communities and getting through this together is the key message.”

Later in the afternoon he posted:

The Chief Constable’s emphatic tone – that he was “reiterating the position” – can hardly have been reassuring when his statement at the Press briefing earlier in the day was clear and unambiguous. He had twice stated “not at this stage”, added “be under no illusion”, and stated emphatically an intention to conditionally set up roadblocks and to search baskets and trolleys.

Moreover, the attempt to brush away such a clear and unambiguous threat with what he later claimed is a “reiteration of the position” is a distortion. Furthermore, the reference to “essential item” is confusing. In his press briefing he had referred to items that were “necessary and legitimate”. The only reference in the law to “essential” in respect of shopping is for “supplies for the essential upkeep, maintenance and functioning of the household, or household of a vulnerable person” (emphasis added, Regulation 6(2)). This would include cleaners, bleach, mops etc. It is odd that the word “essential” is used at all in this paragraph, given that it adds little or nothing to the plain language of supplies for “upkeep, maintenance and functioning” of a household. Surely all items for upkeep, maintenance and functioning” are ‘essential’? There is no reference to ‘essential’ in respect of food and drink, which is what most people will have in their shopping baskets and trolleys – and which most concerned members of the public regarding the Chief Constable’s comments at the press briefing. Adderley’s reference to “essential items”—rather than say “items”—has only served to confuse the public further.

Despite Adderley’s attempts resolve the matter through purported ‘clarification’ or ‘reiteration’, the media was now increasingly focusing on Adderley’s earlier comments.

Concerns escalate

At 1.29 p.m., The Guardian posted details of an exchange with Downing Street on policing: ‘asked about a warning by the Northamptonshire police chief constable, Nick Adderley, that police could start searching shopping trolleys for non-essential purchases, the spokesman said: “Shops that are still open are free to sell any items they have in stock.”’

At 2:15 p.m., Northamptonshire Police issued the following statement:

Again, the police blame is focused on ‘the media’, with an insistence that not searching baskets and trolleys was consistent with what officers had been told from the introduction of the new powers. It repeated what was to become a familiar refrain from Adderley, effectively: you just don’t get it, I had sent a Brief to my officers not to search baskets and trolleys. There is an element of indifference to the public in such chicanery.

At 2.42 p.m., Lewis Goodall, Policy Editor at BBC Newsnight, noted that what Chief Constable was now tweeting was “the opposite” of what he had said in his Press briefing:

Danny Shaw, BBC News Home Affairs correspondent, referred on Twitter at 3.22 p.m. to the “controversy”. Noting Adderley’s full briefing on the Northamptonshire Police website, he added: “That’s pretty clear. We won’t check your shopping now, but we will in the future if people continue to break the rules. I know he’s tried to row back on this during later interviews, but that’s what he said, in a lengthy and cafefully [sic] thought through statement.”

Concerns with Adderley’s comments at the press briefing escalated. At 3.27 p.m., David Gauke, former Justice Secretary in Prime Minister Theresa May’s Conservative government criticised Adderley’s comments in the video. “The threat made in this clip reveals worrying and unacceptable authoritarian instincts”, Gauke said.

Adderley retweeted a retweet from the National Police Chiefs’ Council of 2.55 p.m. of his own tweet of 1.43 p.m. The NPCC started: “.@NorthantsChief has clarified that police will not be searching trolleys.”

Adderley then retweeted a tweet of 3.49 p.m. from the Chief of Staff of Northamptonshire Police advising that at that afternoon’s Facebook Live Q&A at 4.30 p.m. the Chief Constable “will take the opportunity at the start to address the comments in the media today ahead of the questions provided, to provide clarity on the Force’s position.”

Later in the day, the Home Secretary Priti Patel – who is widely viewed as further right than many in the Conservative Party – weighed in, saying that the Chief Constable’s threat was “not appropriate“.

The Facebook Live Q&A

Faced with a wave of criticism, Adderley held a Facebook Live Q&A at 4.30pm, and said, ‘I may have been clumsy in that language’.

But his statement was not simply ‘clumsy’. It was wrong. Not only is there no power in law to search people’s baskets or trolleys for ‘legitimate, necessary’ items (and, as mentioned, very likely amounts to a gross violation of Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights); it sends an entirely wrong message about policing.

Chief Constable Adderley said that he had issued a brief to his Force three days earlier stating, in part: “Northamptonshire Police will not set up roadblocks. Officers and staff of Northamptonshire Police will not carry out basket or trolley searches attempting to ascertain the relevance of the items purchased.” [1:34-1:43 mins].

The content and structure of Chief Constable Adderley’s Facebook Live Q&A presentation also raises concerns. His apology comes very late into the presentation, in the last 5 seconds of a 2-minute, 51-second presentation. The apology is rushed.

It is also troubling that the word ‘sorry’ is delivered as he thrusts his arm forward, which could easily be interpreted as aggressive and dismissive rather than apologetic and conciliatory.

The Chief Constable’s body language and content of his speech during the apology section of the presentation is abrupt. After he says ‘sorry’, he states quickly: “that’s the clarity, that’s the position, let’s move on”. As he does so, he pushes farther away the statement which he had earlier explained is the brief that he sent to this force stating that they will not set up roadblocks or carry out basket or trolley searches.

Having completed his apology, he pushes the brief away again. It is as if the contents of the statement itself have been pushed away, dissociated from him. Chief Constable Adderley comes across as a conflicted individual, apologising only when it is obvious his authority is seriously challenged in such a way as it may have significant repercussions for him.

Chief Constable Adderley avoids fully accepting his responsibility. He stated, “I may have been clumsy in that language”. He never states that it was ‘clumsy’. Moreover, the use of the word ‘clumsy’ diminishes the seriousness of his error.

Chief Constable Adderley diminishes public concern about his statement. He says that his comments had “caused a bit of consternation, certainly on social media”. The insertion of ‘a bit’ and specification that it was on ‘social media’ as though that should not be taken as seriously as if it were raised elsewhere serves to minimise the criticism.

Social media, in fact, serves as a vital public service in enabling swift, extensive, and powerful challenges to abuses of power – as was evident during the #MeToo movement, Arab Spring, and Egyptian revolution of 2011. This is one of the reasons I have also raised on Twitter my concerns about the Chief Constable’s comments and responses (as well as here).

The foregoing concerns undermine confidence in Chief Constable Adderley’s ability.

After the Facebook Live Q&A

After the Facebook Live Q&A, Chief Constable Adderley tweeted or retweeted several more tweets on the matter that evening, insisting on what he referred to as his ‘clarification’ or ‘reiteration’.

In response to one person (‘Nikki’) who had viewed his press briefing, he wrote at 7.33 p.m.: “It absolutely won’t Nikki. I am tempted to release the force brief I wrote 3 days ago which clearly states that this force will NOT carry out roadblocks or trolley checks. I was referring to unnecessary travel. Please be assured, success for us is no enforcement at all.”

Chief Constable Adderley retweeted a post from Sargeant Sam Dodds, Chair, Northamptonshire Police Federation, initially posted at 6.42 p.m.: “Staggered/confused to hear on @SkyNews & elsewhere criticisms by @patel4witham of @NorthantsChief’s messages regarding shifting gear to enforcing Covid law. He’s specifically forbidden road checks/trolley checks in personal call to Insps & above. Couldn’t be clearer…”

The following day, Adderley retweeted a post by his Force announcing the video of the Facebook Live Q&A. He wrote: “This has been my position from day one and will not change. The communities of Northamptonshire have been incredible in their support for the NHS and saving lives as well as supporting us in doing a difficult job. We continue to work hard with them in stemming this awful disease.”

Again, the Chief Constable avoids acknowledging or apologising for the error in his comments at his press briefing about roadblocks or shopping searches.

Action required

Given the obvious and significant difference between the comments on roadblocks and shopping searches by the Chief Constable Adderley at the Press briefing and subsequently, he must also be questioned on his ability to ensure consistent communication and on his understanding of the law, including the Coronavirus Act 2020, The Health Protection (Coronavirus, Restrictions) (England) Regulations 2020, and the Human Rights Act 1998.

It should also be noted that in his interview with Adam Boulton, Sky News, in the morning of the press briefing, Chief Constable Adderley states that his force has arrest powers under the “Coronavirus Bill”. No powers are available under any ‘bill’ unless and until it becomes law. Perhaps he was referring to the Coronavirus Act 2020.

The distinction between a bill and legislation is so fundamental to law that this error by the Chief Constable should also inform questioning as to his ability to understand the law. The matter is made more serious by the fact that wrongful convictions have resulted in other police areas with reference to the law on the coronavirus, such as in Newcastle and in the metropolitan area.

It is significant that it was only after widespread concerns about the Chief Constable’s initial comments that the Police, Fire and Crime Commissioner for Northamptonshire posted again on the subject. This time, he said “Today @NorthantsPolice announced stepping up of enforcement on blatant disregard of Covid19 safety advice, targeting repeat offenders in the county. Today’s message was clumsy but @NorthantsChief was clear from day one there will no roadblocks or trolley searches in Northants.”

The Police, Fire and Crime Commissioner is responsible in law for holding the Chief Constable to account. A general responsibility on the Commissioner to do so is set out in section 1(7)(a) of the Police Reform and Social Responsibility Act 2011, as amended. There are particular requirements in holding a chief constable to account, including the effectiveness of the chief constable’s engagement with local people (section 1(8)(e)). The chief constable’s engagement with local people must include making “arrangements for providing persons within each neighbourhood in the relevant police area with information about policing in that neighbourhood (including information about how policing in that neighbourhood is aimed at dealing with crime and disorder there)” (section 34(92)).

Serious questions now arise as to the ability of the Commissioner to discharge his legislative functions.

The Northamptonshire Police, Fire and Crime Panel is responsible for scrutinising and holding to account the Northamptonshire Police, Fire and Crime Commissioner. Under the Police Reform and Social Responsibility Act 2011, as amended, each police area, other than the metropolitan police district, is to have a police and crime panel. Under section 28 of the Act, such panels must “review or scrutinise decisions made, or other action taken” by the relevant commissioner and “make reports or recommendations” to him with respect to the discharge of his functions (section 28(6)). Accordingly, I have drawn my concerns about the Commissioner to the attention of the Panel.

It is essential, given the public health and legal implications of this pandemic, that public officials, including police, ensure that their communications are accurate and clear, not least as some members of the public remain unaware, unclear or confused about what they can and cannot do. The Chair of the Joint Committee on Human Rights noted in her Briefing Paper The Health Protection (Coronavirus, Restrictions) (England) Regulations 2020 & The Lockdown Regulations, dated 8 April, that some police have given statements which have “muddied the waters” [22].

Chief Constable Adderley’s miscommunication in this matter undoubtedly compounded challenges facing the public. On 23 March, the government ordered all retail businesses, with some exceptions, to close from end of trade that day. Retail businesses that were permitted to remain open included supermarkets and other food shops; corner shops and newsagents, and; off-licences and licenced shops selling alcohol, including those within breweries. Not an insignificant number of people who responded to Chief Constable Adderley made this point.

Despite Chief Constable Adderley’s statements after his press briefing that there would be no searching of baskets or trolleys, there is evidence that the content and manner of these statements confused some people and/ or led to some people to lose confidence in the police.

For instance, one person described the Chief Constable as ‘Buffoon’.

Another, in response to Chief Constable Adderley’s tweet of 11:46hrs, said that the Chief Constable would “lose the public with heavy-handed policing *or* poorly worded communications”.

A series of other tweets throughout the day illustrate further concerns that the Chief Constable had damaged public trust in policing.

In responses to Chief Constable Adderley’s tweet of 1.26 p.m., one person posted:

In response to Chief Constable Adderley’s tweet of 1.46 p.m.: a series of people expressed concerns:

In response to Adderley’s retweet of the National Council of Chiefs of Police, another person referred to what Chief Constable Adderley’s comments revealed about “abuse” of power, adding: “I will never trust a police officer again”:

The damage to public trust from a Chief Constable’s lack of understanding of the distinction between law and guidance, and his tone in communication, is significant. The Home Affairs Committee noted in its report on 17 April 2020: Home Office preparedness for Covid-19 (Coronavirus): Policing.

“It is vital that all forces and all officers understand the distinction between Government advice and legal requirement, and that the tone and tactics they use are appropriate to each. Failing to do so depletes public trust.” [22]

The approach of the Chief Constable during the Press briefing might reasonably have been seen to undermine the concept of Policing by Consent, in particular the requirements:

2. To recognise always that the power of the police to fulfil their functions and duties is dependent on public approval of their existence, actions and behaviour and on their ability to secure and maintain public respect.

and

5. To seek and preserve public favour, not by pandering to public opinion; but by constantly demonstrating absolutely impartial service to law, in complete independence of policy.

Serious concerns also arise as to Chief Constable Adderley’s understanding of human rights and policing, principally Article 7 and Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights – incorporated into the law of the United Kingdom by the Human Rights Act 1998. I quoted earlier Article 8 and some relevant case law. Article 7 provides: “No one shall be held guilty of any criminal offence on account of any act or omission which did not constitute a criminal offence under national or international law at the time when it was committed.”

The Health Protection (Coronavirus, Restrictions) (England) Regulations 2020 were made law on Thursday, 26 March 2020. The College of Policing issued guidance later that day, subsequently amended. Considerable media attention was given to concerns about misunderstanding and confusion by police about the law. Chief Constable Adderley had two weeks approximately to ensure that he understood the Regulations. The press briefing was planned. Chief Constable Adderley had an opportunity to prepare what he would say. His comments were not off-the-cuff or said without an opportunity to reflect.

The Chief Constable’s comments also damaged the reputation of the Northamptonshire Police, with a wide range of national newspapers referring to the Chief Constable’s ‘climbdown’ (for example, The Times, 10 April).

Communication by a Chief Constable of unwarranted or disproportionate powers sends a message to police officers and members of the public to act likewise. It is of concern therefore that a number of Northamptonshire police officers have been acting in a heavy-handed way.

On 9 April 2020, an excerpt of news coverage was posted of a police officer arresting a man in Northampton town centre who had been sitting on a bench. The man informed the officer he was waiting on his partner, gesturing to shops further up the street. It was entirely plausible to assume that this man had been outside with a reasonable excuse, such as obtaining basic necessities. Instead of advising the man on what the law required, the officer physically grappled with the man as he peacefully walked away. The officer was not wearing personal protective equipment. He increased the risk of potentially transmitting the novel coronavirus or of infecting himself. The arrest was at least not proportionate and appears, on the basis of the excerpt, not to have been necessary. Notwithstanding, the officer’s action received an endorsement from Sam Dobbs, Chair, Northamptonshire Police Federation.

At midday on the same day, Sergeant Paul and PC Turner posted on Twitter a video of playing fields and an adjoining path which are part of Upton Country Park, Northamptonshire, with the following text, excerpted: “Sgt Paul and PC Turner have been out this morning in Upton and Hunsbury checking on public spaces. Thank you #northampton for staying home.”

The video shows no-one on the playing fields or on the adjoining path. The implication from Northamptonshire Police is that people should not be in public spaces. This is inconsistent with the balance reflected in the law and guidance that there are on the one hand reasonable excuses for being outside the place where one is living and on the other public health objectives, including restrictions on movement. The indicative and non-exhaustive list of reasonable excuses in law include exercise.

A similar set of images of empty public spaces is collected in a montage in a tweet posted by Northamptonshire Police on 7 April, with the message: “Thank you to everyone who is following Government guidelines and staying at home. Our officers are busy patrolling our towns, countryside and highways and it’s good to see that the vast majority of people are playing their part to help save lives. #NorthantsTogether”:

The tweet was retweeted on 8 April by the Chief Constable, Nick Adderley, with the message: “Incredibly grateful to the vast vast majority of Northants residents who have stayed home, saved lives and protected the NHS. For those who are persistently defying the law your time is up. More follows tomorrow.”

On 11 April, another Northamptonshire Police officer posted on Twitter a montage of two images showing empty public spaces in the police area; one a public street and the other a public park – both areas where the public may lawfully move, with the following message:

The public are not prevented by law or guidance from being out in public in all circumstances. They are not required with reference to the statement ‘Stay at Home’ to remain in the place they are living in all circumstances. They are not required by legislation, as the tweet implies, to not be in public space and to remain within the places where they are living in all circumstances.

Yet, it is entirely plausible to believe that such messaging is understood by some members of the public to mean that the police do not want anyone in public space. This is not a power conferred by law on the police.

It is entirely plausible also that both the comments by the Chief Constable and the tenor of his delivery will have served to consolidate such misunderstandings among his officers.

Broader context

The Chief Constable’s comments about roadblocks and shopping searches, his subsequent responses, and the apparent restrictive interpretation and application of law and guidance by police within Northamptonshire Police resonate with concerns elsewhere in the United Kingdom about heavy-handed policing.

This has included use of drones by Derbyshire Police to attempt, on 25 March, to shame people who may be within their rights in exercising in the countryside; through to police engaging in unlawful arrest or warnings.

A number of police forces have wrongfully arrested and charged persons, such as in Newcastle and the metropolitan area.

On 5 April, Michael Segalov, a journalist, was aggressively confronted by Metropolitan police officers outside Finsbury Park, London. While exercising in the park, he also filmed on his phone a woman who was being marched by police from the park to a Territorial Support Group van outside. One officer, who appears to have disregarded Segalov’s explanation that he was a journalist, and therefore a key worker entitled to also go about his work outside, was particularly aggressive in shouting: “You’re killing people. Go home.” The matter is now subject to a complaint by Mr Segalov’s solicitor.

Heavy-handed policing can damage the relationship between the public, or sections of the public, and the police.

In particular, improper stop and search can cause resentment and undermine policing. The use of stop and search by police was identified as one of the contributing factors in the England riots of 2011, according to The Guardian/ LSE Reading the Riots study.

There is evidence of significant variation in police force implementation of their powers. Over the first weekend that the new laws were in place, 27–29 March, some forces issued over 100 enforcement notices and others issued none, raising questions about how consistently the law was being applied.

The discussion of policing of shopping baskets did not, however, pop out of thin air. On 23 March, Steve Baker MP for Wycombe, in a question to the Home Secretary, Priti Patel, in the House of Commons, noted that some of his constituents wanted police presence at supermarkets. He asked whether the main answer was for the public to buy responsibly. Ms Patel said that it was “not appropriate for police officers to be inside supermarkets”. She added that “everyone should behave responsibly”.

Cambridgeshire Police had to apologise after one of its officers tweeted in the week before Easter: “Good to see everyone was abiding by social distancing measures and the non-essential aisles were empty.” The officer’s tweet was deleted.

Warrington Police tweeted on 29 March that it had issued summonses after “multiple people from the same household going to the shops for non-essential items”. The police later admitted this part of the social media post was an “error”.

On 13 April, an American citizen visiting the United Kingdom to be with her pregnant daughter who lived in London was turned back at immigration control by an officer who said that her journey was ‘non-essential’ – a decision without lawful authority.

On 15 April, police revealed they had withdrawn 39 lockdown fixed penalty notices unlawfully issued to children under powers they incorrectly assumed they had under the Coronavirus law.

Conclusion

The comments by Chief Constable Nick Adderley of Northamptonshire Police on 9 April that his Force would, conditionally, set up roadblocks and search baskets and trolleys had no basis in law or guidance. His subsequent responses that this would not happen came, as illustrated in this article, after mounting and then widespread criticism of those earlier comments. Serious concerns arise about the implications of his comments and his subsequent responses in terms of police accountability and the convention on policing by consent. Further concerns arise regarding the adequacy of the discharge of oversight responsibility of the Chief Constable by the Northamptonshire Commissioner for Police, Fire and Crime. These concerns must be understood, as shown in this article, in the context of evidence of some heavy-handed policing in the interpretation and implementation of police powers during the time of Covid-19.

______________________________________________________________

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Karen Bensusan for comments on a draft of this article. Any errors are my responsibility alone.

.

© Dermot Feenan 2020