(Revised 21 July 2019)

20-minute read

Dermot Feenan

LLB MA LLM Barrister-at-Law FRSA

.

A hate crime occurred on 22 January 2018 at a state secondary boys’ school in Bath, England. Avon and Somerset Police investigated a report that seven white pupils at the school had been involved in an incident where a black pupil was tied to a lamppost on school grounds.

Reportedly, the boy “grew visibly upset after the white boys chained him to [the] lamppost, whipped him with thin branches, and called him names such as ‘n**ger’ and ‘cotton picker’.”

Serious questions are raised by the decision of the police and journalists not to name the school, to publicly hold it to account or to provide adequate public support for the pupil subject to this unacceptable behaviour.

This essay examines the incident. I consider the troubling racial context within which failures in institutional and broader social responses to the incident may be understood. I call upon the authorities to release full details of the incident, to name the school, and to publicly confirm protection and support for the black pupil subjected to the hate crime.

School response

Following the incident, three students were expelled by the head teacher but allowed to return after the board of governors overturned their decision. Four other boys were excluded for a fixed period.

“It just sends the wrong message out to the children. I’ve got a mixed-race son. He’s thinking ‘they’re going to stick up for the white kids but we get in trouble if we do something wrong,’” a father told the Bath Chronicle in March 2018.

A 14-year-old Bath schoolboy, Sagar Chaddha, started a petition, which read in part: “When a young black boy is attacked, assaulted and chained to a post to be continually whipped – something needs to be done!” Chaddha presented the petition of over 2,000 signatures to the head teacher at the school.

An Ofsted report on an unannounced inspection at the school in May said the language used by leaders and governors to describe the incident gave “serious cause for concern”. A key finding was that “leaders did not tell the inspectors about [this] racially motivated incident.”

The chair and deputy chair of the School Board of Governors resigned as a result.

Criminal justice system response

The Crown Prosecution Service said there was enough evidence to charge one of the seven youths with an offence.

The police stated: “A police investigation has been carried out into an incident at a Bath school on January 22, 2018. The incident has been treated as a hate crime.

“As part of our investigation we’ve been liaising fully with the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) and working closely with other partner agencies, including SARI [Stand Against Racism and Inequality], as well as the victim and his family.

“Every aspect of the incident has been taken into account, including the wishes of the victim’s family, and as a result two boys will be subject to a Community Resolution process for their part in the offence.

“Community resolutions are a powerful tool focussing on reparation and are considered to be the most appropriate outcome in this case.

“Community resolutions are always rigorously monitored to ensure they are effective and the involvement of SARI will be a key part of this process.

“We take hate crime extremely seriously and recognise the devastating impact it can have on victims and their lives. There’s no room for this type of crime in Avon and Somerset and we’ll continue to work with our partner agencies and communities to stamp out offences motivated by prejudice or hate.”

They added: “By law, criminalising youths must be deferred when it is felt rehabilitation would better serve, and both CPS and police agreed rehabilitation through the CR process was the most appropriate outcome for this incident.”

The CPS stated separately: “The CPS, through the police, has liaised with the victim’s family and they have been consulted prior to the decision being made.”

According to The Guardian: “The youths all admitted being present during the incident but the extent of their roles varied”.

Impressions

One of the overwhelming impressions from this case is that the school and police have failed to address in a timely or sufficiently serious manner the publicly-important nature of this deeply disturbing behaviour.

Apparently, all parents were not informed about the event until 13 March 2018, only after some parents disclosed details to the press and the Bath Chronicle was going to publish the story. The school issued a statement, in which it said:

“We have today become aware of media interest in an incident which took place in January and involved a group of established friends and related to a single incident of unacceptable behaviour within the school grounds. A full investigation was instigated in line with both internal school procedures and Department of Education requirements, including contact with the police. You can be assured that the school has taken this incident exceptionally seriously and that our absolute priority was, and remains, that the right path is taken for all those involved as well as the wider school community. Given the on-going police investigation and the need to protect all those involved, you will understand that it has been necessary to maintain confidentiality and consequently that the school does not wish to comment further.”

According to one local resident writing on his blog about the case in March 2018, the advice given to pupils in at least three schools in Bath (including the school where the incident occurred) is “Don’t talk about it. Don’t talk about it. Don’t talk about it.”

He continues: “But I get the feeling not talking about it is part of the problem, especially in a town like Bath which revels in architecture built on the blood and bones of the slave trade. […] Here in Bath, it is all being swept under the carpet; the racism, the history, the violence, the effect that has on individuals, the schools, the city.”

A comment on the blog states: “There are so many things wrong with all of this. The school, the parents, the perpetrators all complicit […] They are not protecting the boy in question for his welfare, they are protecting their white privilege.”

Symptomatic of the ignorance about the gravity of the incident are the comments of Roy Ludlow, a former headmaster of the school, who criticised the Ofsted report by saying: “Some boys behaved in a stupid and irresponsible manner but some children behave like that from time to time at any school. The important thing is the way it is dealt with. It was an isolated incident and in no way typical of the boys at [school name] which is, on the whole, excellent.”

Ludlow wrote to Bath Live saying in response to the Ofted report, “This is a school which has consistently achieved some of the best results for boys in the country. It is held in the highest esteem both within Bath and well beyond. The broader opportunities it offers to pupils are second to none. Yet all this is glossed over. Its few faults (and all schools have them) are exaggerated beyond measure.”

What we see here unfortunately is the language of condonation for racism. The former headteacher prioritises ‘results’ and ‘broader opportunities’ over pupil safety and avoidance of racism. ‘Results’ here mean academic results, as measured in scores at GCSE and A Level. Parents and students unconcerned about their white privilege will likely read this former headmaster’s statement and see that their school, and by extension, student achievements are to be measured only in such results and opportunities. They are not challenged to examine social responsibility, social justice, equality, and non-discrimination.

Disclosure of the name of the school allows a thorough analysis of its history, including its admission policy and practice, its composition with reference to ethnicity and social class, whether there have been previous incidents of racial abuse or hate crime, and how the school has responded to any such previous incidents. My own research shows other incidents of abuse have been reported at the school. There was a report in June 2018 of a group of school pupils assaulting another boy on school grounds. The matter was referred to the police. In July 2018, it was reported that a teacher at the school called a French boarding pupil a “dirty croissant”. Concerns have been raised that the school favours the admission of pupils from wealthy families in north Bath at the expense of poorer families in south Bath. Its pupil population is predominantly white. It appears to model itself on independent, fee-paying schools – which are historically and culturally white and elitist. The Bath school follows this model by advertising itself in ways which announce distinct investment in cultural capital for wealthy, middle-class largely white pupils, including ski trips (see image below):

All of the schools’ ‘houses’ are named after dead, white English men, including Kipling – after Rudyard Kipling – who George Orwell described as a “jingo imperialist” who was “morally insensitive and aesthetically disgusting”.

The head teacher of the Bath school was criticised a number of years ago for writing to parents asking them to make voluntary contributions to the school. One parent complained that the head was “attempting to blur the lines” between state and independent schools and of “putting pressure on parents”. She added: “This undermines our state school system. It is putting financial and moral pressure on parents at a time when many are struggling. It ignores the fact that we already pay for state schooling through our taxes.”

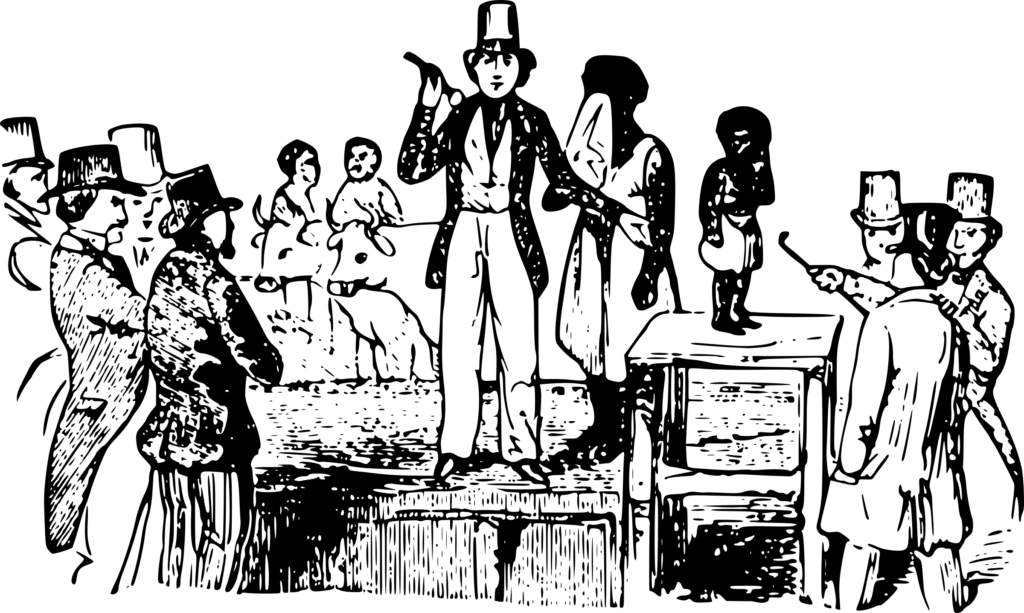

The black pupil in Bath has been rendered invisible by the school, criminal justice system and most journalists, purportedly in the interests of ‘confidentiality’ to protect him. Over 50 years ago another young black student faced a need for protection. Her name was Ruby Bridges. She was the first African-American student to attend a de-segregated school in the US state of Louisiana in 1960 following the ruling of the US Supreme Court that segregation of black and white children in schools was unconstitutional. On 14 November 1960, six-year-old Ruby attended the formerly all-white William Frantz Elementary school in New Orleans. She was escorted to and from the school by US Marshals (see image below).

She was supported by child psychiatrist, Robert Coles, for a year as she settled into the school. Some families also supported Ruby and her family by walking behind the marshals’ car on trips to the school.

Bridges graduated from that school. She worked for 15 years as a travel agent, and now chairs the Ruby Bridges Foundation which she formed to promote “the values of tolerance, respect, and appreciation of all differences.” In October 2006, a school district in California named a school after her. A statue of Bridges now stands in the courtyard of William Frantz Elementary school. Her name was known then. It is proudly remembered now. She was protected and supported. The message from the country and supporters was that she could attend school safely. Those who had harmed her through violation of her constitutional rights and those whose subsequent conduct disrespected the ruling of the Supreme Court and who engaged in intimidation were faced down.

While Ruby Bridges’ situation bears significant differences from the Bath school incident – notably the systemic racial segregation and pervasive violence or threat of violence in the US south – the racial legacy of the transatlantic slave trade still resonates in the experience of the black pupil in Bath, England, in 2018. And, while he may not require a police escort to get to and from school, his experience arises also in a context of racial othering, and he (and others like him) need to know publicly that protection and support will be provided to them.

Malinda Janay, staff writer for Blavity in the US, which describes itself as a “tech company for forward thinking Black millennials pushing the boundaries of culture and the status quo”, wrote in response to the Bath school incident: “Black children deserve to know that someone is standing up for them. This is a lazy way to handle a very serious situation.”

Bath’s historical links with slavery

The city of Bath has long links with the transatlantic slave trade. During its rapid development as a Georgian spa town it attracted the rich and fashionable, including absentee slave-plantation owners from the Caribbean. One, William Beckford (1760-1844), made his home in Lansdown Crescent in 1822 (see below).

Beckford inherited a fortune at the age of ten from his father, including several sugar plantations in Jamaica worked by enslaved Africans. It allowed him to indulge his interest in art and architecture. In the year of his birth, slaves rebelled on one of his father’s plantations. Over 400 were killed. Punishment was brutal. The leader of the uprising was burnt alive.

Much of the venerated architecture in contemporary Bath was paid from wealth derived from slavery; the blood and lives of slaves, including Lansdown Tower, colloquially known as ‘Beckford’s Tower’ – an extravagant library and retreat completed for Beckford in 1827 (see image below).

Another of Bath’s feted constructions is Great Pulteney Street and Pulteney Bridge. They were commissioned by Sir William Pulteney, Earl of Bath, who owned a number of estates and slaves in Tobago and Dominica. Bath’s Circus and Royal Crescent, were designed by John Wood the Elder and completed by his son – whose patron was The Duke of Chandos. He, like many others including the Royal Family, made money in the Royal Africa Company that traded in slaves. Chandos also invested in the Mississippi Company during the French colonisation of Louisiana, which involved both the enslavement of indigenous peoples such as the Choctaw and the transportation of more than 2,000 Africans to New Orleans between 1717-1721.

Bath Abbey features more funerary monuments for slave traders, planters and West India merchants than any other church in Britain. These included Sir John Gay Alleyne 1st Bart. (1724-1801), inheritor of four slave plantations in Barbados, whose father John (1695-1730) is also buried in Bath Abbey.

Bath has a distinctive history in which black people have been chattels, part of an economy of wealth-creation that has funded its infrastructure, consumption, and culture.

While some in Bath have addressed openly its connections with slavery, such as Bath Preservation Trust’s curation in 2007 of a series of exhibitions across five of their sites during the 200th anniversary of the Slave Trade Act 1807, comments from some parents in the wake of the mock slave auction indicate that Bath is still struggling to attend appropriately to the legacy of slavery.

Education

The challenge faced in addressing the legacy of slavery is aggravated by a series of policies adopted by the Conservative Party while in government. In September 2008, the Labour Party-led government under then Prime Minister Tony Blair introduced a new secondary school curriculum to include a unit on the development of the slave trade, colonisation and the links between slavery, the British empire and the industrial revolution.

In 2013, the Conservative-Liberal Democrat Coalition government introduced a programme for study for history within the National Curriculum which was, in the words of the government’s Department for Education, “slimmed down” – with “schools and teachers […] given the flexibility to deal with these topics in ways that are appropriate and sensitive to the needs of their pupils”.

The subject of slavery became a non-statutory component of the curriculum. One of nine examples within a theme ‘ideas, political power, industry and empire: Britain, 1745-1901’, it addresses ‘Britain’s transatlantic slave trade: its effects and its eventual abolition’.

The Department states that it has no record on how many schools actively teach this example within the curriculum. Dr Richard Benjamin, Director of the International Slavery Museum in Liverpool, said that “[s]ome children have no idea that Britain was such a big player in the slave trade until they’re in their mid-20s. We should not be getting to our mid-20s to find that out.”

The removal from the curriculum of the subject of slavery as a compulsory unit was seen as part of a broader ideological re-orienting of the National Curriculum. Indeed, not only is slavery no longer compulsory but the broader context of Britain’s links overseas and the contributions of different peoples to Britain, including Africans has also been dropped. The former curriculum also required that:

Recognition should also be given to the cultures, beliefs and achievements of some of the societies prior to European colonisation, such as the West African kingdoms. The study of the slave trade should include resistance, the abolition of slavery and the work of people such as Olaudah Equiano and William Wilberforce.

The new curriculum makes no reference to these aspects or prominent opponents of the slave trade. In announcing the government’s review for the new curriculum, Michael Gove, then-Secretary of State for Education, said “[w]e have sunk in international league tables and the National Curriculum is substandard.” He specifically named the references in the existing curriculum to Olaudah and Wilberforce. Gove said the review should “give us a world-class curriculum that will help teachers, parents and children know what children should learn at what age”. The subsequent calculated removal of the names of Olaudah and Wilberforce is a symbolic disappearing of lives that matter. Their replacement with the names of traditional white hero-figures such as Churchill and Nelson, reinforces the inferiority of black figures such as Olaudah and the cause of abolition that others, such as Wilberforce, pursued.

The mock slave auction should be understood not simply as an isolated incident, which is how the school, police, and many commentators have framed it, but as part of a systemic and ongoing problem in how Britain attends to the legacy of Empire, ideas of racial superiority, and the entitlement to inflict harm that inform particular aspects of English identity. That ongoing problem reverberates in the government’s “hostile environment” policy that has recently damaged and destroyed the lives and welfare of scores of black people from the “Windrush Generation”.

Alex Raikes, strategic director of the charity Stand Against Racism and Inequality, said after the announcement of the Community Resolution orders following the Bath school incident: “Hate crimes don’t just stop at the door of those actually attacked; they ripple out to instil fear into the wider community it relates to […] many have been deeply distressed by this case.”

Country-wide surge in racism

The incident needs also to be understood within a context in which hate crime has incresed following the vote in the UK in 2016 to leave the EU. In January 2018, data from police forces in England and Wales showed a rise in the number of hate crimes, most rooted in race and ethnicity, over the previous two years at or near schools or colleges. Racist abuse and hate crime against black students has occurred also in higher education institutions such as the University of Exeter and Nottingham Trent University.

The UN special rapporteur on racism reported in May 2018 that that Brexit had contributed to an increased environment of racial discrimination and intolerance. That month, pupils at another school less than eighty miles away from Bath “blacked up” and dressed as slaves for a photograph. That school, Oratory School, in Oxfordshire, is a private school and, like the school in Bath, draws a significant proportion of its students from white, wealthy backgrounds.

My own experience as a northern Irish person living in southern England since 2013 has also been of a steady increase in personal exposure to racism both as pro-referendum rhetoric developed and following the vote, including at a university where I worked – leading me to issue legal proceedings against the employer, which I brought to a satisfactory conclusion. What I have found deeply concerning throughout this period is the way in which some politicians and organisations (including the staff within them) when faced with evidence of racism often engage in similar patterns of obfuscation, denial, cover up, victimisation, and, even, adopting of victim status – as seen in institutional responses to the Bath school incident. The impact of the global financial crisis, the government’s policy of austerity, and the evisceration of state support through disempowerment of the Equality and Human Rights Commission and cuts to Legal Aid, means that staff who might wish to speak out against racism are more likely to fear victimisation, including loss of entitlements or even jobs, if they do so.

That any black pupil can be subject in England to a ‘mock slave auction’ without sufficient accountability and in view of the brutal legacy of slavery is a deeply troubling state of affairs.

Failings in journalism

According to The Guardian coverage on 29 August 2018: “Police refused to give details of the alleged incident”.

We are left with a bizarre statement from the journalist that “a black pupil was believed to have been tied up, put through a ‘mock slave auction’ and subjected to racist abuse” (emphasis added).

The journalist has not only not attempted to establish the facts in a matter of such importance but appears to have ignored the admission by a number of pupils of their involvement in the incident. That admission is necessary to allow the police to proceed with Community Resolution. According to guidelines produced by the Association of Chief Police Officers (ACPO) an officer must when undertaking a Community Resolution: “Discuss the incident or offence with the offender and ensure that the offender has accepted responsibility for the offence”. Moreover, according to the Crown Prosecution Service’s Code, prosecutors should ensure that “the appropriate evidential standard for the specific out-of-court disposal is met including, where required, a clear admission of guilt.” The Crown Prosecution Service confirmed that they had sufficient evidence of an offence to proceed.

The same journalist, and some others, do not name the school – even though the name is already in the public domain and BBC News reported the name on 30 August. While a child is entitled to anonymity to protect against distress and harm (as reflected, for instance, in the automatic restriction under the Children and Young Persons Act 1933 on reporting information that identifies or is likely to identify any person under the age of 18 who is concerned in youth court proceedings) this must be weighed against the principle of open justice where there is a pressing social need to report (under Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights).

Moreover, nowhere in any of this reporting is reference made to an apology being issued to the black pupil.

Failings in criminal justice

Community resolutions, according to the ACPO guidelines, “provide police with a timely, effective and transparent means for dealing with lower level crime”.

It is clear in this case that a ‘timely’ response was not provided. Primary blame for this must lie with the school. Serious questions remain as to why the head teacher remains in post.

The ACPO guidelines also require that any outcome should be “focused on the offender making good the harm caused.” Outcomes can include: ‘apology’, ‘reparation’, ‘actions agreed between the parties’, ‘restorative techniques’.

Avon and Somerset Police have provided no information about the outcomes required. This is a serious failing. Was an apology given to the victim? What action(s) have the pupils subject to the Community Resolutions agreed to undertake?

And, drawing upon the name of the measure itself: whose ‘community’ is served, and how was determination of this established? We simply cannot assume that the police or the perpetrators can be relied upon to satisfy these questions.

More broadly, we are told nothing about what precisely the school will do to educate students about slavery in any meaningful way. Will they explain how slavery was and continues to be inextricably bound up with the power, status and wealth of Britain? How treating a person as a chattel leads to manifold cruelties, and how in particular the pursuit of profit in such a slave-as-chattel economy operated economically, politically and socially? How the transatlantic slave trade and slave-worked plantations enabled in turn the development of capitalism and of industrialisation? Will they detail the injuries – economic, cultural, physical, psychological, and symbolic – to Africa and African bodies? Will they explore the complicities of their forebears and the contemporary advantages which that complicity and their country’s historical engagement in the trade still yields? Will they help the students understand how othering anyone on the basis of the difference of their skin colour, ethnicity, or nationality can create profound and lasting injury? Will they help those white students to radically and critically examine their own conscious and unconscious biases, their privilege and sense of entitlement to subject another non-white body to degradation, humiliation and potential trauma?

The Community Resolution in this case may satisfy an element of justice, but criminal justice is also a public matter. It is not a private matter. Criminal justice must be concerned also with public concerns and address the needs of any potential victim and potential suspect.

In the absence of sufficient information about the Community Resolution in the Bath school incident, it might reasonably be questioned whether justice has been done in this case.

Conclusion

The offence here is not simply the chaining, assault and insult. These actions are also racially aggravated. They have been conducted by white pupils against a black boy within an overwhelmingly white environment. They mimic one of the most horrendous moments in black history; the slave auction, which itself sits within a context of racial othering and violence. The re-enactment of such an auction is not simply an offence against one individual, or even against a school, it is against black people generally and against the humane values that led to, and continue to be waged against, prohibition of slavery. The failure to provide details of the incident, to name the school, and indeed to provide public protection and support for the black child is not acceptable.

.

© Dermot Feenan 2019