Andy Billman’s ‘Daylight Robbery’

10-minute read

Dermot Feenan

LLB MA LLM Barrister-at-Law (non-practising) FRSA

.

Introduction

The late Susan Sontag observed in her collection of essays On Photography, ‘the camera’s rendering of reality must always hide more than it discloses […] only that which narrates can make us understand’. I was reminded of this observation following an exhibition of photographs by Andy Billman titled ‘Daylight Robbery’, 22-26 June 2021, part of the London Festival of Architecture, which purported to document ‘the bricked-up windows of London, examining natural light’s role in architecture’.

The description for the exhibition elaborated on this role and introduced a reference to wellbeing in this examination; specifically, ‘the role that light and air play for our wellbeing in the spaces we inhabit’. The description added: ‘many of these windows would have been blocked off to avoid the Georgian-era Window Tax, which stipulated that the more windows one had, the more one had to pay’. The exhibition description concluded by stating that the ‘blocked-up windows’ were ‘remnants of a time when a price was actually placed on light and air’ and that the windows ‘have particular resonance with life during lockdown’.

I show in this article that a number of these statements about the exhibition are misleading, incorrect or insufficient, and, combined with claims about the relationship of air, light and wellbeing, seriously miss important relevant aspects of the relationship between, variously, environment, socio-economic disadvantage and wellbeing. I use these observations to draw out some broader implications for reading photographs, which has resonance beyond photography.

Blocked-off or blind windows?

A significant number of the windows featured in the exhibition were not ‘blocked off’(or ‘bricked up’/ ‘blocked up’) to avoid the window tax. The exhibition comprised sixteen photographs of buildings in London, England, as shown in the exhibition catalogue (below).

One of the photos is ‘Hazlitt Road’. It shows part of the rear of Hazlitt House on Milson Road (see image below from Google Street View), which joins Hazlitt Road. A chimney runs behind blind windows – a decorative feature which has the outline of what appears to be a window but which is not in fact a window. This architectural feature is not unique to England, as illustrated in an article on blind windows in the city of Lviv in eastern Europe.

The windows in Hazlitt House have not been ‘blocked off’. The house has a prominent position on the corner of the street. It stands alone and therefore offers considerable aesthetic potential from several aspects. However, it occupies a narrow plot which has a relatively small space between the rear of the house and the backs of the neighbouring houses. Given the narrowness of the depth of the house and the limited space for siting chimneys, a decision appears to have been made to place the chimney flues on the inside of the rear wall. In doing so, the exterior arrangement of blind windows matches the arrangement of functional windows on the front of the building. An aesthetic balance is retained on the four exterior walls of the property.

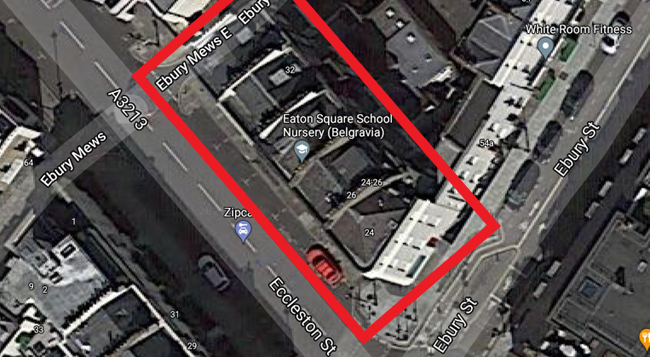

A similar blending of form and function is evident in another property featured in the exhibition: ‘24-32 Eccleston Street Early C19’. The photograph of the property is taken of the Ebury Street end of a terraced block of five properties (see Google Street View image below), all of which were built at the same time.

The image is striking. It is one of newer styles of buildings popular in London in the early nineteenth century where the façade, rising four storeys above street level, conceals the roof. Understanding urban architecture as also a function of surroundings, this makes sense. The building faces a similarly styled building across the road. Across from them on an opposite corner is another similarly styled building. The Eccleston Street terrace complements the character of the adjacent buildings.

But why the blind windows on the Ebury Street side of 24-32 Eccleston Street? The answer is revealed partly by looking from above and laterally – using different framing. In Google Maps, it is just possible to make out that each property has a large chimney for approximately ten flues. These would likely have connected to fireplaces on each floor: basement, ground, first, second, and top (attic). The plot for the terrace meant that it was not possible to run the chimney flues along the wall on Ebury Street. In any event, that wall was part of a corner property which contained ground floor retail premises. The door to the shop was built into the distinctive rounded corner. It has since been blocked up, but the original windows on either side on the ground floor remain (see below).

Access to the rear of the premises and upper floors is via the door on Ebury Street. The chimney flues for that property were placed on the separating wall between No. 24 and No. 26, Eccleston Street. Each of the other properties in the terrace followed this logic. The flues for the property at the opposite end of the terrace then needed to be placed on the exterior wall (see satellite image below).

Rather than leave the façade at the opposite end of the terrace clear of any features, the architect mirrored the effect on the Ebury Street end with another set of blind windows (see image below).

A similar façade is featured in the exhibition; in the photograph of ‘Scarsdale Villas c. 1850-64’. The photo shows only part of the elevation on the second and third floors of a dwelling at the corner of Scarsdale Villas and Earls Court Road. The image below, taken from Google Street View on Earls Court Road, shows a similar raised frontage to conceal the roof from the street. At the top of the gable end can be seen a chimney stack, with eight pots. The chimneys would have run down the inside of the gable wall, making it impossible to install windows in that wall in a way that would have retained the balance in the exterior design elsewhere. In order to preserve the style of the frontage on the gable wall, it, too, featured blind windows.

Opposite that gable wall is another property, captured in the exhibition photo ‘Scarsdale Villas c. 1850-64’. The image is of the gable wall of 67 Earls Court Road, which adjoins Scarsdale Villas. It is part of a much longer terrace running on the eastern side of Earls Court Road. The terrace was completed long after the repeal of the window tax in 1851, decades after the ‘Georgian Era’. As with the terrace on Eccleston Street, only the end properties contain blind windows – for largely aesthetic reasons.

The exhibition also features a photograph titled ‘Strathmore Gardens c. 1858’. The photograph in the exhibition is simple: an arched, blind window on the ground floor of the property. Stepping back, it is possible to see that the blind window is one of four which run almost the height of the property’s chimney (see the elevation from Google Street View, below).

Moreover, this property (and similar such property) was certainly not the home of the urban poor who were partially deprived of light and air as a result of window tax. It is a substantial property with eighteen windows visible from the street, including bow windows in the basement, and on the first and second floors fronting onto Palace Gardens. The misleading information in the exhibition description about the period in which the window tax operated, the difference between ‘blind’ and ‘blocked-off windows’, and the attenuated framing of the photo—specifically what it leaves out—undermines the general claims about built environment, taxation and wellbeing in this exhibition.

Another of the buildings featured in the ‘Daylight Robbery’ exhibition is ‘Pitt Street c. 1844-64’ (below).

In fact, the building (whose postal address is 17 Gordon Place) was built in 1872/3 over 20 years after the repeal of the window tax.

These five properties which I have mentioned are not connected in any way to the window tax. It strains credulity for the exhibition to claim therefore that ‘many’ of the windows in the exhibition would have been blocked off to avoid the Georgian-era Window Tax (setting aside the error in attributing the tax only to that era, given that the tax was introduced during the Restoration and then extended, after the Georgian Era, into the Victorian era). But even if the vagueness of the word ‘many’ is contested via-à-vis the proportion of properties featured, this still does not excuse the overall impression left by the exhibition that when windows were ‘blocked off’ this necessarily adversely affected health or that everyone’s health was affected equally by windows being blocked up.

In a number of those photographs the so-called ‘blocked off’ windows were a feature of the original construction or of re-building for another purpose. The exhibition also failed to provide an account of how the tax disproportionately affected certain groups of people. Here, it’s necessary to look more closely at the window tax.

Window tax

The tax was introduced by legislation in 1696; repealed in 1851. The tax was applied initially to properties with 10 windows. This did not have much effect on most of the population who lived in rural dwellings. Their homes tended to have fewer windows. However, England experienced exceptionally rapid urban growth in the eighteenth century which saw increasing numbers of people living in multi-occupancy rental properties. The growth of cities also led to an increase in live-in servants, even if by the time of the repeal of the window tax there may have been some decline in the number of live-in servants. Landlords and masters sought to offset the tax by either passing on the cost in increased rent and/or by avoiding further tax by bricking up windows. When the tax was extended in 1766 to include houses with seven or more windows, the number of houses in England and Wales with exactly seven windows reduced by nearly two-thirds.

The tax was designed to be progressive, since windows were assumed to be an index of the value of houses. However, by the early eighteenth century the adverse effects of the tax on health were starting to be documented.

Despite the purpose of the legislation, some believe (incorrectly) that the window tax gave rise to the phrase ‘daylight robbery’, a belief reinforced in the title of the exhibition.

Daylight robbery

There is no evidence that the phrase ‘daylight robbery’ derives from imposition of window tax. The Oxford English Dictionary, an authoritative source, provides three definitions (two of which are relevant here).

(1): ‘A robbery committed during daylight hours, often characterized as particularly conspicuous or risky; the action or practice of committing this type of robbery.’ (2): A colloquial use, said to be originally and chiefly British: ‘Blatant and unfair overcharging or swindling.’

The first record of the second usage occurs in print in 1863. There is no reference to windows in the Oxford English Dictionary definitions. Nonetheless, some non-authoritative sources perpetuate the linkage between the phrase and window taxes.

Wellbeing: health and complexity

The description to the exhibition claims to demonstrate the photographs’ relevance to ‘our wellbeing’ during so-called ‘lockdown’ in the COVID-19 pandemic. While the concept of wellbeing is not defined in the description, and is in any event notoriously labile, it might reasonably be understood to include the concept of health given the well-established linkages in contemporary discourse between health, wellbeing, and access to light and air, as illustrated in the 2019 book by Nick Baker and Koen Steemers, Healthy Homes: Designing with Light and Air for Sustainability and Wellbeing.

However, the exhibition does not recognise complexity in the conditions which affect wellbeing, certainly health, following the introduction of the window tax and during so-called ‘lockdown’, including the socio-economic conditions causing certain groups to be more likely to suffer adverse health effects.

All the buildings featured in the exhibition were, at the time of construction, exclusively private residential buildings, except Partner House and the Ebury Street side property in the Eccleston Street terrace – which was built for residential and commercial use.

The primary focus in the exhibition on homes ignores the fact that the majority of the adult population in modern times spend most of their waking hours at work in another building (excluding the interruption to this phenomenon as a result of the pandemic).

Access to air and natural light in workplaces also has significant impact on health. Yet workers often have less control over access to natural light and air than in their own homes. A survey published in 2019 of 1,601 professionals working in corporate office environments in the US found that 85% said the air quality in their home or outdoors was better than at work.

During the so-called ‘lockdown’ there was, among the exceptions to the stay-at-home requirement, an exemption for travel by ‘key workers’; broadly, those working in vital sectors such as health and social care, supermarkets, transport, utilities, education, and crucial public services such as policing. The Office for National Statistics reported on the socio-demographic profile of key workers early in the pandemic: with 30.5% of employees in the bottom three income deciles (monthly earnings of up to £1450) considered as key workers in March/April 2020, compared with 26.4% in the top three income deciles (monthly earnings of up to £3250). Many of these sectors are characterised by workplaces with noticeably less access to light and air than is the case in the private sector. The windowless, air-conditioned retail superstore selling food and drink is an example of such a workplace that would be known to most members of the public as consumers.

Moreover, the effect of the UK government’s ‘Stay at Home’ guidance was that those without access to gardens were more likely to experience adverse health effects in relation to lack of access to fresh air and natural light. The poor are least likely to have gardens, especially in towns and cities. Yet, it is well-documented that exposure to green space has a positive impact on health and wellbeing. The disproportionate response of some local authorities, such as Tower Hamlets Council in London, during the early stages of the pandemic to close public parkland exacerbated this socio-economic disparity.

The assumption inherent in the exhibition—that having windows which allow in air is a sufficient good—ignores mounting evidence about the adverse effect of polluted air on health, especially in the city in which the photographs were taken (London). A focus only on windows also ignores the principal causes of pollution caused by release of nitrogen oxide and sulphur dioxide: industry and road transport, respectively.

It is also necessary to note that science had no understanding of viruses during the period of the window tax. It was not until the late-nineteenth and early twentieth century that virology emerged as an established explanation for illness and mortality. To the extent that the exhibition focuses on light and air, but does not mention ventilation specifically, it underplays the preponderant risk of infection through airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and the importance of appropriate airflow and associated quality of air to minimise exposure to the virus.

This exhibition focuses only on windows during ‘lockdown’. The effects of ‘lockdown’ on health are complex and go well beyond the role of windows and access to light and air. While research on the effects of the ‘lockdown’ on health is still developing, it is known, for example, that there were substantial reductions in primary care contacts for acute physical and mental conditions following the introduction of restrictions. Increasingly, studies show particular adverse mental health effects, including elevated psychological distress especially among women and the young, and an increase in depression among adults generally, predominantly among women and younger adults, with more pronounced increases among students. There is also mounting evidence that BAME communities have been disproportionally hit hardest by the pandemic.

More substantial adverse effects from SARS-CoV-2 arose as a result of government policies such as releasing old people from hospitals directly into care homes without first testing them for infection by SARS-CoV-2; the Prime Minister’s failure to hold his adviser Dominic Cummings accountable for breaches of coronavirus law and guidance, which gave rise to the so-called ‘Cummings Effect’ in reducing compliance with this law and guidance among the general population; delaying ‘lockdown’; and, refusing to close travel to and from India at a time when the ‘India’ variant of coronavirus was spreading rapidly with serious adverse effects on health.

It is also not clear from the exhibition how precisely the so-called ‘lockdown’ was understood to affect access to light and air. The initial law restricting movement to the home did permit exercise as one of the exceptions to the general rule. Exercise was not defined but it was understood to mean walking. Government guidance reinforced the policy underpinning the exemption. Restrictive interpretation and application of law and guidance by police within some police forces led to heavy-handed policing, as noted in my article ‘Policing in the Time of Covid-19’.

Conclusion

The exhibition ‘Daylight Robbery’ did not distinguish the blind window – an aesthetic feature in architecture – from a window that was bricked-up to avoid payment of window tax. This lack of distinction affects the exhibition’s claim that the window tax and the windows featured in the exhibition have, with reference to access to light and air during the so-called ‘lockdown’ during the SARS-CoV-2, resonance for ‘our wellbeing’. The exhibition does not acknowledge how groups defined by significant socio-economic differences were affected differently by the window tax and that these conditions do not simply ‘resonate’ with conditions pertaining under SARS-CoV-2. Developments in virology and in particular in the understanding of the role of airborne transmission of the present coronavirus means that concern about light and air is an insufficient response to dealing with risk of infection from the virus given the indicated need for ventilation and good air quality (amongst other interventions) in reducing the risk of transmission.

The concern of the photographer behind the exhibition with access to light and air in accommodation is laudable. The exhibition does serve, partially, as a timely reminder that in the past people suffered ill-health because of the effects of government intervention, including through the behaviour of those who seek to protect their profit at the expense of the health of the poor and others who are unable, or least able, to protect their own health. This also has resonance today. However, there is a more complex story about taxation, wellbeing and the purposes of built environment which is not captured by the exhibition, which could be captured – and which this article seeks, at least in part, to redress.

The exhibition serves as a reminder to view documentary photography critically. This need for critical engagement extends beyond the study of photographs. It extends, at least, to similar choices and techniques – framing, focus, perspective, and depth of field – that apply elsewhere, including in one of my own fields of work: socio-legal studies.

.

© Dermot Feenan 2021