10-minute read

Dermot Feenan

LLB MA LLM Barrister-at-Law FRSA

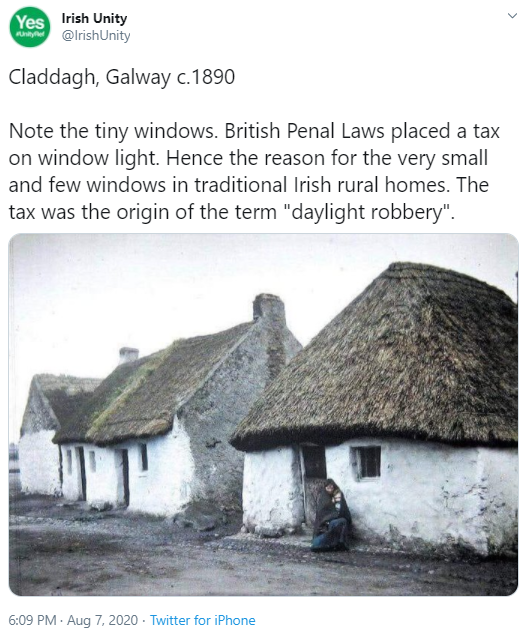

On 7 August 2020, @IrishUnity posted a tweet which attracted several thousand likes. The tweet comprised text and a photo of several small thatched, whitewashed buildings outside one of which crouched a woman, carrying an infant. The first line of text stated: ‘Claddagh, Galway c. 1890’. It was followed by several short sentences: ‘Note the tiny windows. British Penal Laws placed a tax on window light. Hence the reason for the very small and few windows in traditional Irish rural homes. The tax was the origin of the term “daylight robbery”.’

The tweet is neat, well-written, and packs in a lot of information. It includes an image of the thatched cottage which, as Professor Finola O’Kane Crimmins argued in her chapter ‘A Cabin and not a Cottage – The Architectural Embodiment of the Irish Nation’, is appealing partly because it stands in for Ireland itself. By juxtaposing the cherished image of the cottage and presence of mother and child with the ‘British Penal Laws’, ‘daylight robbery’ and attenuated building design, the tweet was bound to appeal to those with certain ideas about Irish history. It was an intriguing tweet. Yet, it contained multiple falsehoods.

I set out in this blog to correct those falsehoods, and in doing so to expand an understanding of Ireland – including of its laws and socio-economic history – which hopefully will encourage further research into the window tax, but, as importantly, understanding of the accommodation and livelihoods of the majority of the people.

1. ‘British Penal Laws’

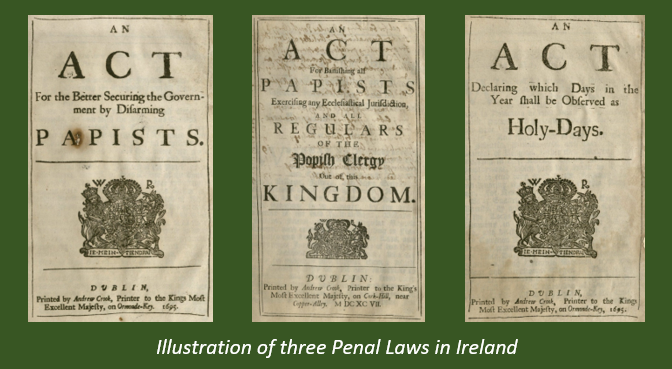

The ‘Penal Laws’ did not place a tax on ‘window light’. The Laws were introduced by England in the Elizabethan era to uphold the Church of England against Catholicism and Protestant non-conformists by imposing penalties, forfeitures or civil disabilities.

The Penal Laws initially applied throughout England. They were introduced in Ireland in 1695, with the Education Act. They were repealed from the 1770s. The Government of Ireland Act 1920, s. 5(2) provided that any existing such law shall cease to have effect in Ireland.

The Penal Laws have, nonetheless, had a profound effect on Ireland, especially as the bulk of the population were Catholic. Edmund Burke described the Laws as “well-fitted for the oppression, impoverishment and degradation of a people as ever proceeded from the perverted ingenuity of man.”

The University of Minnesota has this online listing, with the text, of the Penal Laws in Ireland. The database is searchable chronologically and by subject matter.

2. ‘Traditional Irish homes’

The concept of ‘traditional Irish home’ in the tweet is questionable. The photo depicts cottages in The Claddagh, 1913. Humans have lived on the island of Ireland for over 12,500 years, inhabiting various dwellings, including huts, cabins, cottages, and, of course, bungalows.

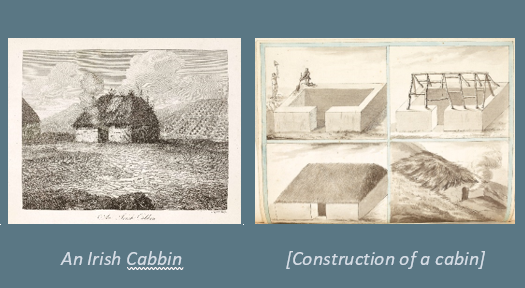

The design of the Claddagh cottages predates the introduction of the window tax legislation in Ireland; as can be seen in this example from County Monaghan, 1771. It was a design prevalent across Ireland.

3. Very small and few windows

Many Irish homes in the 17th through 19th century had, quoting the tweet, ‘very small and few windows’ principally because of cost (including of installation/ repair/ replacement: lintels, frames, glass, putty, paint), but also energy conservation, comfort, and different aesthetic tastes from today.

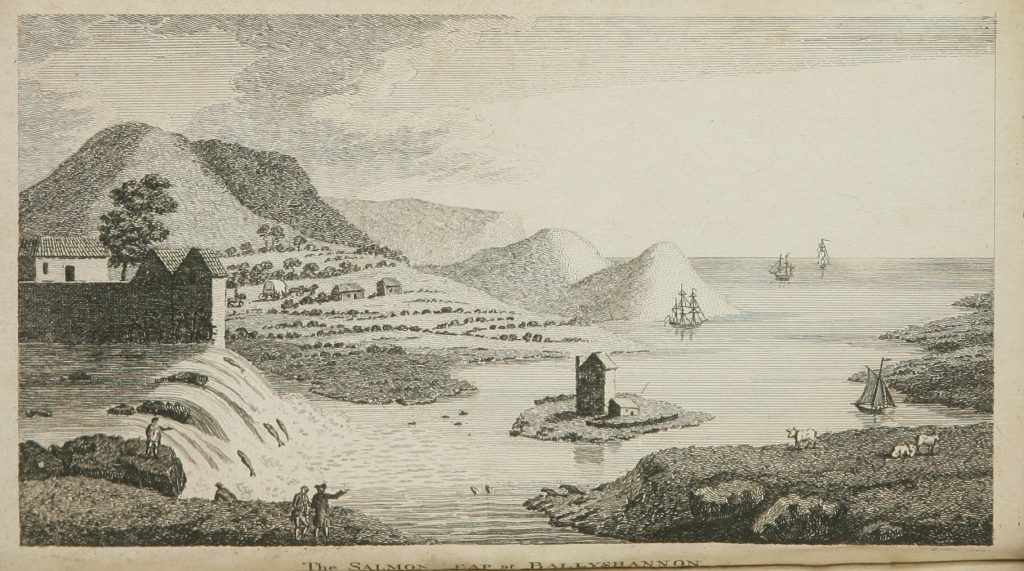

In Richard Twiss’ drawing ‘Salmon Leap at Ballyshannon’, County Donegal, for his book A Tour in Ireland in 1775, written a few years before the ‘window tax’, several cottages are visible: all with one door and one window only.

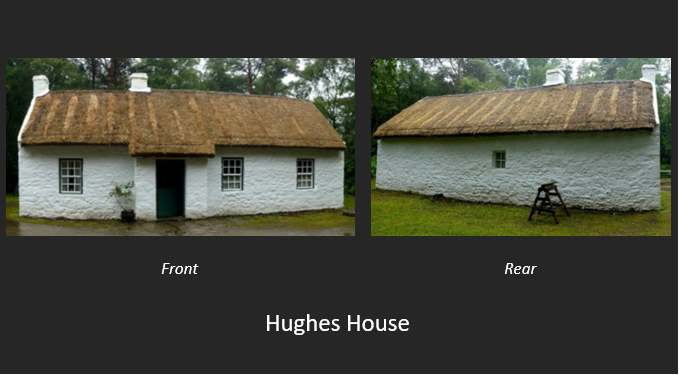

Even well-built dwellings had few windows. An example is the Hughes House to which the parents of infant John Joseph Hughes – later Archbishop of New York – moved a few years after his birth in 1797. The façade shows three windows; around the back, just one light.

The following illustrations, by Arthur Young for A Tour of Ireland (published 1780), shows a common form of dwelling in Ireland: the cabin. In the 1841 census, 40 percent of rural houses were single room mud cabins, with few, if any, windows.

In The Miseries and Beauties of Ireland (1837), Jonathan Binns published the drawing of Owen Gray’s Farm House, near Bellananagh, County Cavan (below). It shows a home to Gray, his wife and their 11 children; the only light admitted through the doorway.

There are other depictions of the single-roomed cabin across the country. Just over a decade earlier, Henry Blake, in his Letters from the Irish Highlands (1825), wrote of a cabin in Connaught with no window and a hole in the roof by way of a chimney.

William Evans painted numerous such dwellings on his journey between Galway and Leenane. Of those that are sufficiently detailed, the common feature is a single door, a window, and hole in the roof to allow smoke to escape (as illustrated in ‘Stormy Landscape with Thatched Houses and Figures’, 1838).

Photographs in the early part of the 20th century continue to show such cabins with a single door and a window (see example, below, by William A. Green on Inishowen, County Donegal).

Such infrequency and size of windows in rural dwellings was not unique to Ireland; as evident in the following examples from different countries in the period. First, a weaver’s cottage on the island of Islay, Scotland, 1772.

This drawing by Ludvík Kohl, a Czech-Austrian painter and draughtsman, of a farmhouse in central Europe in the late 18th century, also shows few, and small, windows.

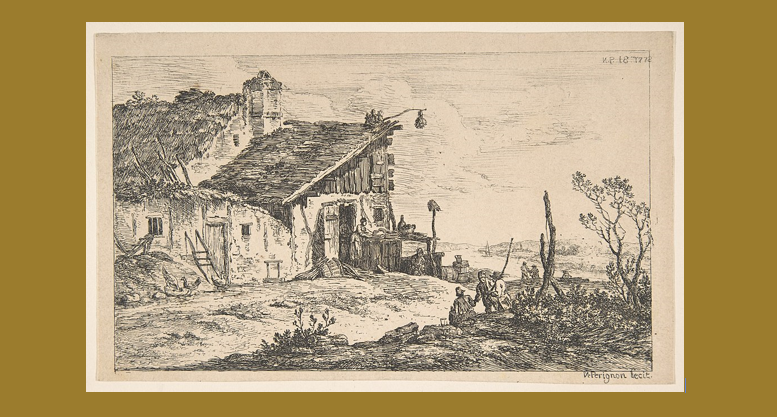

Similarly, in this drawing in 1772 by French painter and draughtsman Nicholas Pérignon, there is a rustic dwelling with few and tiny windows. It was probably drawn while he toured in Italy or Switzerland.

4. The ‘window tax’ Act(s)

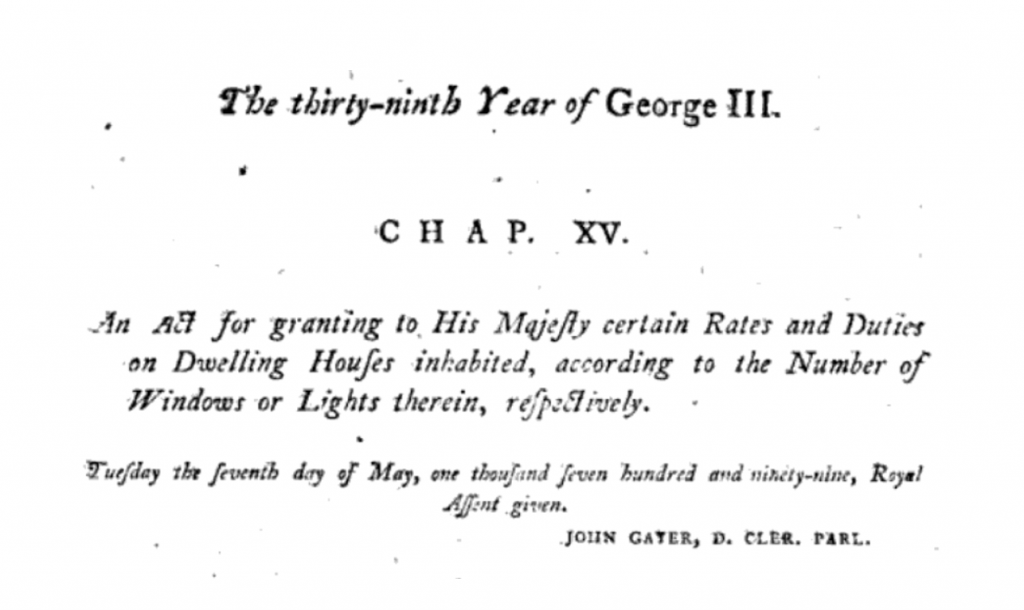

‘An Act for granting to His Majesty certain Rates and Duties on Dwelling houses inhabited, according to the number of Windows or lights therein, respectively’ (39 George III c.15) was passed by the Parliament of Ireland, receiving Royal Assent 7 May 1799.

In general, tax was payable on and after 25 March 1799 by the occupiers of every inhabited dwelling of five or more windows at a rate indexed to the number of windows or lights in the dwelling on or after 1 January 1799. It was not a tax on ‘window light’, as asserted in the tweet.

Given the number of windows and lights in the average dwelling in the Claddagh, it is unlikely that tax would have been imposed in the area.

The tax was designed as a property tax since windows were assumed to be an index of the value of houses – as noted in a House of Commons debate on the tax shortly before its abolition (HC Deb 9 April 1850 vol 110 cc68-99).

The legislation which introduced the tax in Ireland was repealed in the 19th century. Moreover, the legislation did not, as implied in the ‘British Penal Laws’ tweet, impose tax according to the size of a window or light.

A ‘window tax’ had already been introduced in England and Wales in 1696 by ‘An Act for granting to His Majesty severall Rates or Duties upon Houses for making good the Deficiency of the clipped Money’. It was extended to Scotland.

5. The date of the photo

The ‘British Penal Laws’ tweet states that the photo was ‘c. [about] 1890’. In fact, it was taken in May 1913 by French women Marguerite Mespoulet and Madeleine Mignon-Alba.

6. The Claddagh Cottages

The Claddagh cottages photographed in 1913 are not dissimilar in appearance, though, to those depicted in early 19th century drawings. An unfinished watercolour by William Evans titled ‘Spanish Arch, the Claddagh in Distance, Galway’, 1838, shows Claddagh cottages with indistinct hints of apertures.

The following drawing from 1843, ‘Spanish Arch, the Claddagh in Distance, Galway’, published in Ireland: Its Scenery, Character, &c., is based on the Evans watercolour of 1838. Note, however, that detail has been added to the cottages which was not evident in the original.

While Samuel Reynolds Hole described the dwellings in the Claddagh in 1859 ‘for the most part windowless’ (A Little Tour in Ireland), most of the dwellings depicted elsewhere have at least one window. It is necessary to exercise caution towards some 19th century English visitors’ accounts of the Claddagh.

As Dr. Fidelma Mullane argues, these accounts were ‘defined by the nativist assertion of the writers, an assertion that defined not just the urban and civilised – the ‘Englishman’, but also, by juxtaposition, ‘other’ – the native and uncivilised Irish.’

Photographs around 1900 show one door and a small window on either side, sometimes with a tiny rear window (see below). Occasionally, the dwellings had a side window.

There were also smaller dwellings, with one door and one window (evident in the photo by William A. Green, below).

There is a similarity in the external appearance of the dwellings in the area in 1838 and in 1913. I have found no images of the Claddagh earlier than 1838 (though this is a position necessarily limited as the research for this piece amounted to several days’ online searches).

It is plausible that the design of the Claddagh cottages in 1913 is the same as, or at least not significantly different from, those that predated the introduction of the window tax (though caution needs to exercised regarding biases and stylistic influences in drawing).

However, Dutton noted in his Statistical and Agricultural Survey of County Galway (1824) that the residents of the Claddagh ‘are exempt from the payment of all taxes whatsoever, by what law, except that their houses in general are not taxable, I am ignorant.’

If Dutton’s statement reflects the true position regarding collection of taxes in the Claddagh and extended throughout the previous 25 years, the window tax may have had no impact on architecture in the Claddagh. Further analysis of historical records seems warranted.

7. Tax does affect building

Professor Meredith Conway of Suffolk Law School noted, in an article in the Columbia Journal of Tax Law, the unintended effects that taxes can have on architecture. It should come as no surprise that the evidence goes well beyond Ireland.

Conway notes how people sought to avoid tax on their buildings, including in dwelling houses, throughout history: such as the growth in family monasteries during the Byzantine Empire due to the exemption given to monasteries in the first known fireplace tax.

In the early 17th century, the Dutch government, concerned at the growth of house construction in Amsterdam, enacted a tax on houses based on frontage. This gave rise to construction of narrow houses which are a feature of parts of Amsterdam to this day.

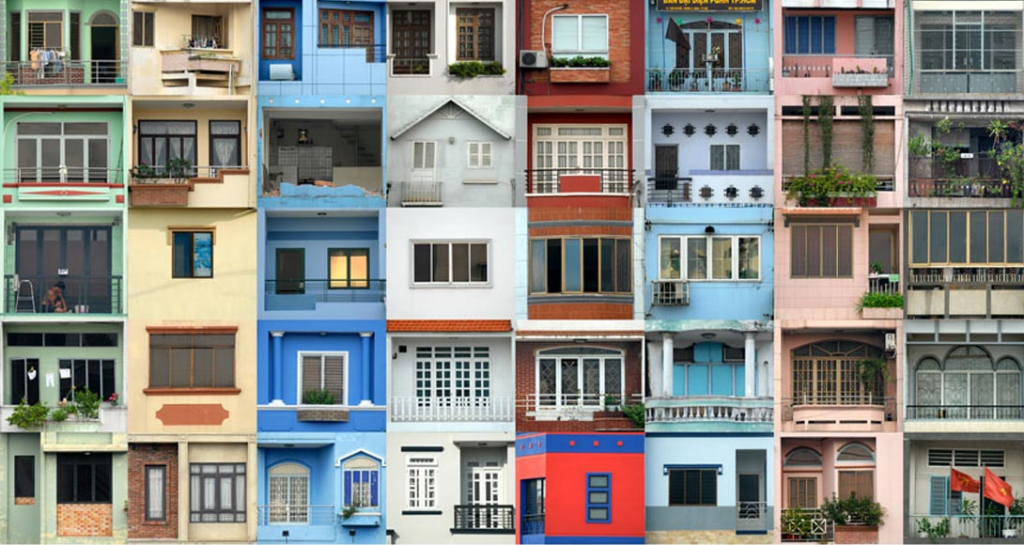

Similarly, taxes relative to the frontage of buildings which were imposed during the Li Dynasty, from 1428 to 1877, in Vietnam, led to the construction of ‘tube’ houses in Hanoi. These narrow buildings were typically built up to five floors.

There is evidence that occupants of dwellings in Ireland did block up windows. In some cases, this is attributed to the window tax. In other cases, no explanation is provided. Dutton noted in his 1824 survey:

Dutton also noted that ‘the sleeping accommodation of servants is most grossly neglected in many houses’ and that in one of the ‘first houses’ in the county a physician attending a housemaid ill with fever ordered that the window of her room, which had not been opened in twenty years, be ‘broken open’.

Given the dates, the closing of the window may have coincided with the introduction of the window tax. If so, the owner’s wish to avoid tax took precedence over the welfare of staff. Dutton also noted how the walls of cabins collapsed because landlords would not invest in adequate roofing.

The lack of repair (or absence) of windows was also witnessed in the capital, Dublin. Writing in 1834, Henry D. Inglis noted ‘houses and cottages in a half-ruined state, with paneless windows or no windows at all’ in The Liberties and other neighbourhoods towards Phoenix Park in the western part of the city.

More drastically, Theo McMahon noted that a number of houses in Ulster had to be demolished due to the inability of the owners to pay the window tax (‘The Window Tax in Monaghan, Fermanagh, Tyrone and Cavan, 1800’, Clogher Record (1976) 9(1): 110-112).

8. ‘Daylight robbery’

There is no evidence that the phrase ‘daylight robbery’ derives from imposition of ‘window tax’, as claimed in the ‘British Penal Laws’ tweet. The Oxford English Dictionary, an authoritative source, provides three definitions (two of which are relevant here).

(1): ‘A robbery committed during daylight hours, often characterized as particularly conspicuous or risky; the action or practice of committing this type of robbery.’ (2): A colloquial use, said to be originally and chiefly British: ‘Blatant and unfair overcharging or swindling.’

The first record of the second usage occurs in print in 1863. There is no reference to windows in the Oxford English Dictionary definitions. Nonetheless, some non-authoritative sources perpetuate the linkage between the phrase and window taxes.

9. Getting facts right

There were numerous falsehoods in the ‘British Penal Laws’ tweet. A second’s research would reveal the errors in that tweet and the fact that it was doing the rounds in August 2018 on Twitter (below) and corrected then.

It also appeared on Reddit around the same time in 2018; and was also corrected by those replying.

It’s important to get facts right, especially when talking about law. A risk in repeating falsehood is that not only is truth corroded but commitment to the pursuit of truth can be diminished.

If, as I hope, there is to be unification on the island of Ireland – between Northern Ireland and Ireland – it will most likely come from careful attention to facts, careful listening to diverse experiences, and ever more careful attention to different interpretations of history.

I’m concerned to see that a practising lawyer liked the ‘British Penal Laws’ tweet – not least because of involvement in a case where avoidance of anything that could be perceived to involve political bias is essential to avoid compromising the client and significant broader issues legal at stake.

The analysis of the tweet serves as a reminder, if any is needed, of the importance of interrogating and understanding the production, distribution and consumption of imagery and accompanying text.

While some have challenged the ‘British Penal Laws and window tax’ tweet, few, however, have been willing to point out that the inadequate housing hinted at in the tweet had myriad constitutional, legal, political, fiscal, economic, and social causes as a result of governance in Ireland.

For instance, most Irish people then did not own their own property. In 1870, 97% of those farming the land were tenants. Generally, they had no legal right to demand repair and, until the Landlord and Tenant (Ireland) Act 1870, could not seek compensation if they did carry out repairs.

Hely Dutton had noted in his survey in 1824 of housing that it was, typically, ‘wretched in the extreme’. He recorded the following attitude to tenants: “What the devil do I care how they live, so as they come to work when I want them, and pay me my rent.”

Dutton added, ‘I have been often at a loss to account for the callousness of some landlords in this country, that could patiently see around them such miserable dwellings for their tenants, whilst their horses and hounds have every attention paid to their comfort.’ Landlords were not short of funds.

For instance, Sir John Forbes notes in his Memorandums of a Tour of Ireland (1852) that the Coolattin Estate in County Wicklow brought in rent of £40,000 and other land in County Kildare brought in £2,000 annually. That is approximately £5,900,000 today.

Despite the numerous errors in the tweet, the Penal Laws in Ireland were part of British (but at its core English) colonialism that subordinated Irish people; including by dispossessing them of land, removing their title to land, displacing them, and, effectively, subjecting them to exploitative landlordism.

Whether cabins and cottages were windowless or not may have had less to do with window tax than with a centuries-long system of British rule, consolidated through the Anglo-Irish estates, which confined most Irish people to inferior accommodation and precarious livelihoods.

Many references to window tax in the historiography of Ireland are brief, inadequate and sometimes inaccurate. Much of the analysis of the tax is, perhaps unsurprisingly, deficient. I hope to have shown here by correcting facts that there is also much more to learn about Ireland through consideration of the tax.

Some of the complexity and effects of tax law in Ireland in the relevant period are explored in depth in Kanter and Walsh (eds) (2019), Taxation, Politics, and Protest in Ireland, 1662-2016, and in Dickson’s 1983 chapter, ‘Taxation and Disaffection in Late Eighteenth-Century Ireland’.

______________________________________________________________________________

Thanks to John Levin (@anterotesis) for The Statutes Project, which helped me locate the 1799 Act. The Project’s primary aim is to put parliamentary law online, for free, in multiple and easily reusable formats. It’s an important aim. My respect to John for his work.

©DermotFeenan 2020

Great piece of analysis, Dermot and so good to see myths and falsities such as this one being so thoroughly corrected.

Fabulous piece of research, so lovely to hear a thorough analysis presented so clearly! You wouldn’t happen to know the history of Carrickmines castle?! I can see the ruins straddling forlornly amidst the undergrowth of Carrickmines roundabout. I can’t find a point of access to the site and would love to hear more about it than I can find on google! I live in Carrickmines.

Dear Annette Walsh: Thank you for your feedback. I’m afraid I wasn’t aware of Carrickmines Castle until you drew it to my attention. I see from the Wikipedia entry about the Castle that a group of ‘Carrickminders’ and others (some named) were involved in trying to protect the Castle, so perhaps it might be helpful to try to contact them directly to find out more about the Castle’s history? Best wishes, Dermot.

Interesting article. Interesting correction .

Truly excellent piece of research. I have never studied law, but often had to study older extant legislation as part of my work in arts management. For example, when running a theatre in Sligo, I discovered that only certain theatres in Dublin and Cork could obtain special bar licences (at the time) and the law was on the statute books since Grattan’s parliament. It was initially introduced to fund the establishment of the Rotunda Hospital.

But in relation to the window tax, I am curious about where the term The Law on Ancient Lights comes from. When Project Arts Centre rented an old clothing factory premises on South King Street in the 1970s, we sought to remove four free-standing boards that had been erected at a great height on adjoining land which blocked the light coming in through four windows. Our Chairman Colm O Briain (RIP) was a Barrister but ultimately failed in the battle to have them removed, and the landowners next door cited the aforementioned law.

As to the temporary window tax (above 5 windows), I wonder was it introduced to equalise somewhat the tithe which poor farming land-renters had to pay, while those owning urban property largely escaped?

Further, the lack of windows in cabins was surely due to the fact of their construction from mud and/or turf. Very difficult to build door or window opes that would last? W.A. Green also took a very charming photograph of such a turf house in County Tyrone. It does have a door and one window though.