15-minute read

Dermot Feenan

LLB MA LLM Barrister-at-Law FRSA

.

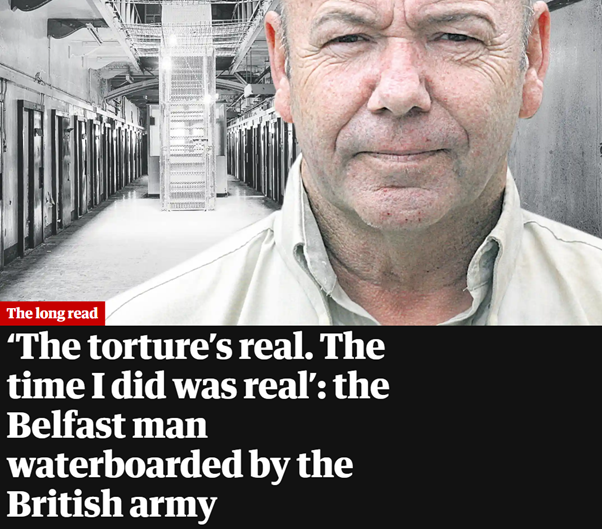

There is much to value in Ian Cobain’s recent Long Read in The Guardian on the experience of the late Liam Holden in seeking justice for the unlawful treatment, including waterboarding, assault and battery, inflicted on him by the British Army in Belfast and the implications for such cases given the UK government’s Northern Ireland Troubles (Legacy and Reconciliation) Bill, but it also contains flaws.

Chief among the merits of the piece is not only the fact of the reporting but the depth of reporting of a case, particularly in the wake of the High Court’s award of damages, including for that waterboarding, to Mr Holden’s estate on 23 March 2023—which has shamefully received no coverage in significant sections of the British media, including The Times, The Daily Telegraph, and Daily Express.

That depth of reporting also contains an empathetic incorporation of details about the impact of the unlawful treatment on Mr Holden and his family which are largely unreported elsewhere. These details particularize and humanize the harms often glossed over in the media and occluded or ignored by narrow legal categories. I refer to this as ‘humanizing journalism.’

I take time in this essay to acknowledge those merits, not least because too much reporting on the conflict insufficiently recognizes the humanity of the individuals injured or killed in the conflict and the harms caused to their loved ones, friends, and community. I lived through much of that conflict. I knew scores of people killed or injured during the conflict. I worked as an academic at universities in Northern Ireland for over ten years on issues related to our transition from conflict to peace. Some of that work focused on the importance of human rights-based mechanisms for securing truth, accountability, and justice.

I also trained and worked for a time in and around Belfast as a therapist, which necessarily included people harmed by that conflict. This allowed me to work with scores of individuals who, due to histories of abuse, mental health issues, harmful drug use, and serious and prolonged socio-economic disadvantage, never went to university and were marginalized within a society that was already heavily segregated by religion. They were an invisible population to most of my academic colleagues. Working as a therapist also allowed a deep understanding of the connections between the conflict and those individuals’ histories.

In addition, the physical and psychological injuries I had personally incurred from being in that divided society contributed to my decision to live outside Northern Ireland. I retain interest in and links with the region.

I have a very strong personal and ethical commitment to ensuring that the conflict and people harmed in that conflict receive due respect in how they are reported, especially given that from the vantage point of England, where I now live, knowledge and understanding of that conflict, including by some journalists, is often woefully deficient, as I alluded to in my essay ‘An English Conceit: ignorance, forgetting, and amnesia regarding Ireland’. Concerns about media reporting on Northern Ireland long predate that essay, as illustrated by the series of edited collections The British Media and IrelandTruth: the first casualty The British Media and Ireland—Truth: the first casualty and The Media and Northern Ireland.

I find myself needing increasingly in England to reinforce that commitment in the context of both personal experience of anti-Irish racism in England and acute awareness of laws, policies, and rhetoric from a hard-right Conservative government in Westminster that undermines that respect and empathy, and that presses ahead with measures that jeopardize attempts to secure truth, accountability, and justice.

Liam Holden: a brief summary

For those unfamiliar with Mr Holden’s pursuit of justice, we need to go back fifty years to the streets of Belfast.

In 1972, the then 18-year-old junior chef was arrested at his home in the almost exclusively Catholic and Nationalist/ Republican area of Ballymurphy, Belfast, by a soldier in the 1st Battalion, Parachute Regiment, on suspicion of being a member of the IRA following the fatal shooting of another member of Regiment four weeks earlier.

Mr Holden was subjected to waterboarding, hooding and threat to kill by soldiers in the Regiment if he did not confess to shooting the soldier. Following this unlawful conduct, Mr Holden confessed to shooting the soldier. There was no other evidence against Mr Holden. In 1973, he was convicted and sentenced to the death penalty. That sentence was later commuted to life imprisonment. Mr Holden served 17 years in prison before being released on licence in 1989.

Mr Holden maintained his innocence.

In 2002, the Criminal Case Review Commission reviewed the case, considering new evidence which had not been put before the trial court. It referred his case to the Court of Appeal. The appellate court ruled in 2012 that in light of that evidence the conviction was unsafe.

Mr Holden subsequently successfully applied for compensation for miscarriage of justice.

He was entitled to seek damages for other harms which were not resolved by that claim for compensation. He initiated civil proceedings against the Ministry of Defence and the Police Service of Northern Ireland in July 2014.

Mr Holden died in September 2022. The legal proceedings were continued by Mr Holden’s children, as executors of his estate.

The High Court’s award in March 2023 to Mr Holden’s estate comprised damages for the waterboarding, hooding and threat to kill, malicious prosecution, misfeasance in public office, aggravated damages, and special loss.

Humanizing journalism

Media reporting on the conflict in Northern Ireland has not only too often failed to humanize those killed, injured or bereaved during the conflict but has rendered others as undeserving of any shred of humanity through the use of othering, unalterable and damning labels such as ‘terrorist’. In 2015, research on media representation of children and young people in Northern Ireland, for instance, found that they “spoke at length about the absence of their voices and opinions in news coverage and the media’s failure to address issues affecting their lives.”

Growing up during the almost constant reports of fatalities, explosions, ambushes etc., the main broadcast media (BBC Northern Ireland, UTV, and commercial radio) would often simply announce an incident along the lines of “Catholic man, aged 28, shot dead in the Ardoyne area of Belfast.” We would learn even less of the life of the member of the British Armed Forces shot dead or blown to bits in a bomb explosion.

Perhaps the incessant nature of these incidents made further reporting difficult or impossible. There is evidence that exposure merely to the numbers of people who suffer can lead to ‘psychic numbing’. There is also a cost to a lack of attention to the lives of those who suffer: dehumanization. It can attenuate and slowly deprive us of the capacity to feel empathy and to exercise compassion. This effective anaesthetizing of those affective ethics of empathy and compassion towards others may also inure us to our own complex feelings, including our own suffering.

However one seeks to understand and analyse the conflict, it is essential, at the very least, then to—in the words of the Ulster poet John Hewitt—”bear in mind these dead.” For Hewitt that ‘bearing in mind’ was not only the recitation of numbers or names (important though they may be in the correct context). Rather, it included a telling detail of each life, “the skipping child hit by the anonymous ricochet” and “the elderly woman making tea for the firemen when the wall collapsed.”

In my own experience of that conflict and its aftermath, those details included the frequent nightly screams from my neighbour, alone next door, widowed decades earlier when her police officer husband was shot dead while helping out in his brother’s shop, his killer never found.

I recall, too, the grey, grim faces of yet another friend’s family bereaved by the sectarian murder of their student son, and the almost inevitable speculation about a surviving brother; “is he going to join the IRA?”

Time passes but it does not necessarily heal. Therapy for those bereaved and/ or injured requires at the very least paying compassionate attention to their suffering. And compassionate attention requires empathy, the ability to try to understand another’s perspective, very probably of a life lived very differently from one’s own. This may take, among other things, time, patience, and a setting aside of one’s own ego-driven preoccupations. It also requires attentiveness and kind responsiveness. The best journalism does so, too. Better still, it shows willingness to understand that person’s experience within a broader social context.

Such humanizing reporting is evident in the book Lost Lives by journalists David McKittrick, Seamus Kelters, Brian Feeney, Chris Thornton, and David McVea. The book is a record of the over 3,700 lives lost in the conflict in the north of Ireland. The authors record details of every death in the Northern Irish Troubles. In addition to standard demographic information on the age and location of each death, the authors selected from among media reports other telling details, including the account of a first responder or the effect of the loss on one of the bereaved—a spouse, father, or child. The reader is left with an indelible image of each lost life and the jagged edges of suffering left by that absence for those loved ones. For the authors, the book served an ethical purpose. It should, they wrote, “serve as a lasting reminder of why Northern Ireland should never again return to full-scale conflict, a lasting reminder of the sadness and the pity of it all, a lasting reminder that war is hell.”

Ian Cobain’s Long Read empathetically incorporates details about the impact of the unlawful treatment on Mr Holden and his family. These details particularize and humanize the harms too often glossed over in the media and occluded or ignored by narrow legal categories such as assault or battery.

Absent from the recent court judgment, these details include the fact that Mr Holden’s mother had a breakdown when he was sentenced; the relationship with his girlfriend collapsed when he was transferred to The Maze prison 10 miles southwest of Belfast; his discouraging of his family from visiting the prison because “he found their obvious distress deeply upsetting.”

Also included by Cobain is the fact that it was not until after Holden was released on licence after 17 years in prison that he was diagnosed with PTSD (Post-traumatic Stress Disorder), a condition most likely experienced and, therefore, not treated while he was in prison, and certainly not early enough to have helped him cope better.

Liam Holden could not get a job after release. “Nobody would give me a job,” he said. He was also harassed by a police officer who regularly stopped and searched him on the streets near his home, until he lodged a complaint.

His wife, Pauline, who he had married after that prison release, died in 2000, leaving him to raise their daughter and his stepson alone. It would be another 12 years before his case was referred to the Court of Appeal and 10 more years before the most recent civil action.

These details carefully show the profound harms from that miscarriage of justice. But Cobain also humanizes the British soldier who was shot dead: a teenager from Cheshire, engaged to be married to his childhood sweetheart, who’d joined the Army because he needed a job.

Cobain’s piece refers to the soldier, Private Frank Bell, as an 18-year-old, but someone claiming online to have served alongside him, said he was actually 17; amended in Army records because the minimum age of entry to the Army was then 18. In any event, so young.

Beyond these humanizing details, Cobain provides information about the British Army’s use of abusive interrogation (and, consistent with the overall thrust of his piece, is admirably humble in not citing unnecessarily his own work, in this case a well-regarded book, A Secret History of Torture, in which he examines that practice in more detail).

Flaws

Alongside the merits in Cobain’s piece, there are several key flaws. These are not minor flaws. They affect an understanding of the social and political reality and possibilities for people in Northern Ireland.

(i) The reductive phrase ‘Northern Ireland’s two communities’

Cobain refers to ‘Northern Ireland’s two communities.’

There are, though, more than ‘two communities’ in Northern Ireland. It is, at least, helpful to note that the Belfast Agreement recognizes not only separate British and Irish identities but joint British and Irish identity.

But Northern Ireland is more diverse than these narrow identities allow. The point is well made in a chapter ‘More than two communities: Those who are both, neither, other, and next’ by Colin Coulter, Niall Gilmartin, Katy Hayward, and Peter Shirlow in Northern Ireland: a generation after Good Friday: Lost futures and new horizons in the ‘long peace’. The authors note that “the population of Northern Ireland is increasingly ethnically and linguistically diverse and made up of people who were born outside the region.”

(ii) Failure to note that the government’s ban on the ‘five techniques’ was secured, at least in part, by widespread outrage at their use and the conclusions of the Parker Report

Cobain refers to widespread knowledge in 1973 of the British Army’s abuse of prisoners in Northern Ireland and then refers to the announcement in Parliament by the then Prime Minister Ted Heath that there would be no further use of an interrogation method known as the ‘five techniques.’

One might be forgiven for thinking from this account that Ted Heath was simply benignly intervening to correct the errant British Army. In fact, reports of such abuses had circulated for years, culminating in the Parker report of 1972 which recommended that these techniques not be used.

The use of these techniques was also subject to widespread condemnation, as noted by Dr Samantha Newbery in her book Interrogation, Intelligence and Security: Controversial British Techniques.

Stan Orme, a Labour MP, raised in Parliament on 19 October 1971 the issue of ‘the interrogation of internees in Northern Ireland.’ The Home Secretary responded that this would be ‘investigated’ by the Committee of Inquiry chaired by Sir Edmund Compton. That Committee was appointed on 31st August 1971, with the following terms of reference:

“To investigate allegations by those arrested on 9th August [1971] under the Civil Authorities (Special Powers) Act (Northern Ireland) 1922 of physical brutality while in the custody of the security forces.”

Those Terms and the powers of the Inquiry were deemed by concerned observers as inadequate, hence the appointment of Parker Inquiry in November 1971 specifically to investigate ‘procedures for the interrogation of persons suspected of terrorism’.

Cobain’s framing of Heath’s decision ignores the political and other pressures that were necessary to bring the government to this point.

(iii) Minimizing of the number of people killed by security forces in the conflict

Cobain also writes: “the security forces were responsible for only around 10% of the 3,700 or so deaths between the late 1960s and 1998 […] They concern allegations of unlawful killings, state collusion and the use of torture” The word ‘only’ and that percentage minimizes those deaths.

An alternative formulation would be to write: “The British Army and security forces in Northern Ireland killed approximately 370 people.” The gross number is impactful.

If deaths at the hands of the security forces had occurred in England on the same scale—that is, proportionate to the total population—tens of thousands of people would have been killed. That framing underscores the scale (and associated significance) of the killing in a way that a relatively low percentage alone cannot do.

(iv) Failure to acknowledge settled facts and significant consensus regarding the conflict

Cobain makes claims and pose questions about the conflict which undermine what we do know and what is agreed regarding that conflict. This has significant implications for progressive politics.

He writes: “Even the most fundamental questions remain unsettled.” Yet, some fundamental issues are settled.

He continues: “There is little consensus over the legitimacy of political violence, the responsibility for that violence, or the motives of those involved.” This framing ignores the significant consensus that does exist on these matters.

Cobain uses reductive dichotomies in asking: “Was it a war or a series of crimes?” The two are not mutually exclusive categories, as the concept of war crime shows. But that conflict was more than a binary between war and crime. It involved elements of both.

He also asks: “Was the conflict essentially sectarian – Catholic v Protestant, nationalist against unionist – or […] a struggle between Irish republicans and the British state?” Yet the conflict involved all of those things. It has also become increasingly clear, especially as official records are opened and as various participants in the conflict lift the lid on the details about their involvements, how the distinction between some of those dichotomies was blurred, for example through collusion between the state and paramilitaries.

Cobain goes on to write that people (by which he means people generally in Northern Ireland) have no “shared narrative”. This may seem axiomatic in societies experiencing conflict, but the vast majority of people in Northern Ireland voted in a referendum to support the Belfast Agreement in 1998. An even greater majority now accept that there should be no return to violence. This ‘shared narrative’ is tangible and has profound effect. It cannot be underestimated nor should it be forgotten or remaindered by loose, inattentive language about what is shared and not shared.

Without some settled ‘fundamental questions’ it is impossible for parties to a dispute to settle or to accept a judicial decision. It is for this reason that legal proceedings are designed to settle such questions early so that matters under dispute can be argued by the parties to the dispute and adjudicated upon. Without some shared consensus it is difficult if not impossible to have functioning institutions, including those that were agreed in the Belfast Agreement. For those of us seeking to work through and beyond conflict, it becomes essential to find some common ground, some ‘shared narrative’.

(v) Apolitical framing of the Northern Ireland Troubles (Legacy and Reconciliation) Bill simply as a government bill rather than a measure consistent with the ideology of one of the most right-wing Conservative governments in modern history

Cobain also fails to recognize that the government that proposes “an official British history of the conflict” and tabled the Northern Ireland Troubles (Legacy and Reconciliation) Bill is one of the most right-wing Conservative governments in modern history.

This omission is important because it ignores the significant role of political ideology at a key moment in British (and by extension northern Irish) history. The Conservative Party’s proposals for Northern Ireland are part of a wider hard-right ideological shift in government in the UK, especially since Brexit.

This shift is reflected in law, policy, and political discourse, including attempts to roll back human rights, curb the judiciary and legal profession, undermine the rule of law, weaken the power of important groups such as unions, undermine mechanisms of accountability such as the parliamentary standards system.

This shift extends to strengthening the role of the police and army. The hard-right’s associated tactic of so-called ‘culture war’, seeks to invalidate legitimate critique of those institutions such as the armed forces and monarchy which are then increasingly presented as emblematic of a necessary patriotic identity, even as the tactic draws more on an obviously divisive, regressive nostalgia for Empire rather than the needs of a modern, diverse and democratic country.

Significant sections of the media in Britain, including the The Daily Telegraph, The Times, and Daily Express support this ideological direction of travel.

The fact that those newspapers— have not reported on the award of damages to Liam Holden’s estate for the waterboarding, unlawful detention etc. by the British Army is part of this ideological context.

Therefore, the final flaw in Ian Cobain’s piece is to omit reference to this ideological context. Without that context, readers are left no wiser about an important dimension to the techniques of denial, concealment, and frustration of truth-seeking and justice by the State and what might then be done to counter those techniques.

These flaws are at odds with the humanizing journalism evident elsewhere in Cobain’s piece because they also tend towards reductive categorization of people, disappear the human struggles involved in effecting political change, and omit reference to the ideological and associated political context within which peoples’ success or failure in securing political change exists.

Conclusion

There are significant merits in Ian Cobain’s account of one northern Irish man’s pursuit of justice.

Those merits include not only the fact of reporting that pursuit of justice, especially in the context of a widespread failure to do so elsewhere in substantial sections of the British-based press, but the depth of reporting of that case—an empathetic incorporation of details about the impact of the unlawful treatment on the late Liam Holden and his family which are largely unreported elsewhere. I repeated those details in this essay because, in view of the failure by many journalists to pay sufficient attentiveness to the impacts on Mr Holden and his family and the lives of the many others still suffering from the conflict, it seems necessary to reinforce those details. Those details particularize and humanize the harms often glossed over in the media and occluded or ignored by narrow legal categories.

The importance of such reporting is underscored by the need to counter a right-wing direction of travel in the UK, especially in England, which omits such humanistic understanding of the complexity of the conflict in the north of Ireland and its legacy—an omission that seems not only inextricably linked to the anti-Irish racism that I have experienced, researched and documented in the country but in the increasingly regressive ideas about accountability, human rights and compensation that are manifested, in part, in the government’s Northern Ireland Troubles (Legacy and Reconciliation) Bill.

Still, Cobain’s piece contains a number of flaws that muddy that understanding and which ill-serve the potential achieved through hard-won, largely peaceful settlement resulting from the Belfast Agreement.

These flaws include the use of the reductive phrase ‘Northern Ireland’s two communities’ to describe the population. They include the failure to acknowledge certain settled facts and significant consensus regarding the conflict. Those flaws also extend to a minimizing of the number of people killed by security forces in the conflict and a failure to note that the Conservative government’s ban on interrogation practices known as ‘the five techniques’ was secured, at least in part, by widespread outrage at their use and the conclusions of the Parker Report. Relatedly, Cobain frames the Northern Ireland Troubles (Legacy and Reconciliation) Bill simply as a government bill rather than as a measure consistent with the ideology of one of the most right-wing Conservative governments in modern history. These flaws also impede awareness and action. Readers are less likely then to understand and analyse the techniques of denial, concealment, and frustration of truth-seeking and justice by the State that not only affected Mr Holden but have affected and continue to affect many others and what might then be done to counter those techniques.

While these flaws aren’t fatal to the overall thrust of the piece, they illustrate all-too-frequent ways of misreporting on the conflict and associated politics by many journalists based in England, which have adverse implications for people in Northern Ireland. They are serious flaws to the extent that they misrepresent part of what is happening, and should continue to happen, in Northern Ireland to hold perpetrators of unlawful abuse and killings to account, to establish a factually correct record, and in some cases, to secure justice.

.

(c) Dermot Feenan 2023