5-minute read

Dermot Feenan

LLB MA LLM Barrister-at-Law FRSA

.

The salary of £20,111 pro rata offered by the national legal charity JUSTICE for their recently advertised Linklaters Legal Fellows is troublingly low and may deter talented candidates from disadvantaged socio-economic backgrounds. The narrow profile of staff and the board at JUSTICE may well exacerbate this risk. In this blog, I set out further details about the fellowships and explain why the salary and profile are problematic with reference to socio-economic, gender and racial inequality, particularly in relation to such jobs as stepping stones into the legal profession.

The average salary for a cleaning job in London is £22,492 according to Totaljobs: that’s almost 12% more than JUSTICE will pay someone in this post. Candidates for the posts at JUSTICE are required to have a UK law degree or equivalent, carrying an average student loan debt of £45,000.

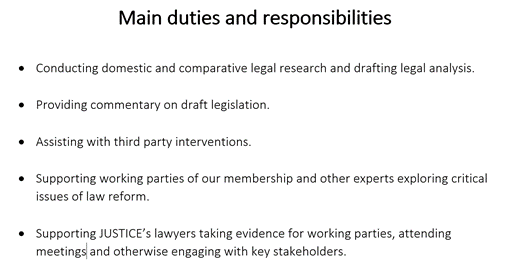

The main duties and responsibilities for the role (below) are similar to those of a research assistant in the university sector, with a starting salary (including London weighting) for an entry-level post of £33,114.

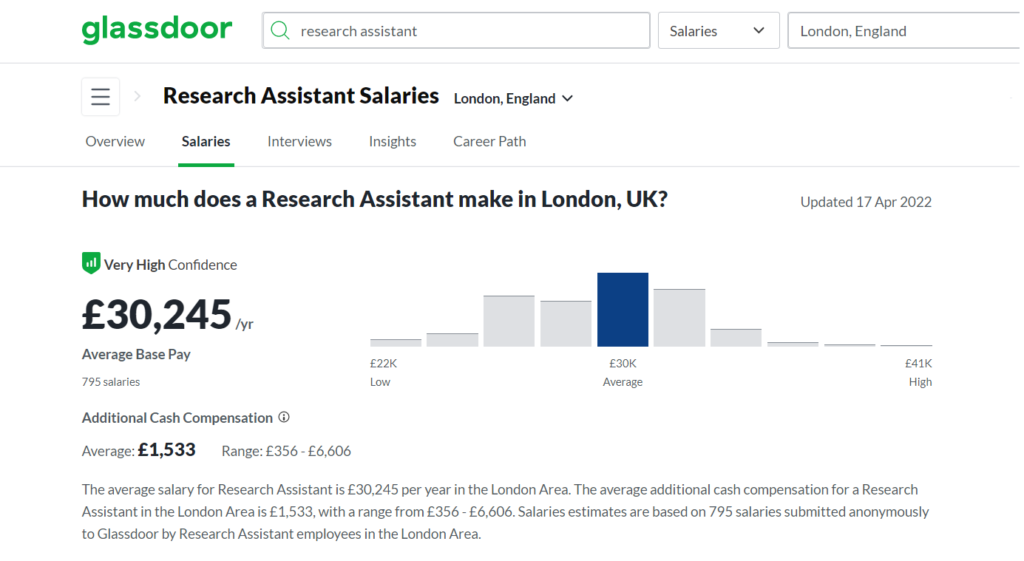

Not all research assistant posts are held in universities. There are some in the civil service, business, and the third sector. Still, according to recruitment agency Glassdoor the average salary for a research assistant in London is £30,245 per year.

London is the most expensive city in the UK for rental accommodation. It also has amongst the highest public transport costs in the country. Even if someone travels from home outside London into JUSTICE’s offices in the City of London, thus saving on rental in London, they will incur significant travel costs. These costs come out of salary.

The salary doesn’t go far. And it won’t allow much for saving or exigencies.

The headline duration of the post (6 months) might also fail to attract talented candidates who need—quite reasonably—sustainable income, especially if they have any dependent/s. Will a single, graduate mother from a working-class background who is caring for her young child feel it is worth applying for a six-month post with a low salary in the slim hope it might lead to further employment in a precarious legal labour market? I doubt it.

The job details go on to state that this duration ‘is flexible and can also be offered part-time over a longer time frame with a minimum of three days a week.’ This might go some way to alleviating concerns of candidates who might need extra income, but why not pay more?

Such high status, low-paid, short-term posts are likely to attract people who are well-off, can depend on financial help from others or sustain low income for 6 months, thus narrowing the social class of people interested in the posts. This approach to hiring risks reproducing inequality.

It’s not as if Linklaters, the sponsors of these posts, are poor. In the financial year 2020-21, they had revenues of £1.67 billion and profits per equity partner of £1.77 million. So, paying a Legal Fellow less than the average salary of a cleaner in London seems a bit off.

The already privileged have access to additional opportunities. The Bonavero Institute for Human Rights, University of Oxford, offers an eight-week paid fellowship at JUSTICE. Their maximum rate is more, pro rata, than that offered by JUSTICE for its legal fellow posts.

Universities such as Oxford are able to provide numerous paid fellowships to their students due to their huge wealth compared to most other universities; further advantaging the small number of students admitted to those institutions, who then apply to charities such as JUSTICE.

Given the problems with pay and duration of these posts, let’s also look at JUSTICE’s staff and board composition. It has 18 staff members. All are visibly white, 16 are female. This may deter Black, Asian or minority ethnic (BAME) candidates, especially if male.

Given that JUSTICE is based in London, where Black and Asian people make up over 30% of the population (see graph, below, based on the last published census data), this staffing profile doesn’t look representative.

The 12 members of JUSTICE’s Board are almost exclusively visibly white, with only one visible Black member. And, setting aside their Chair, the majority of its members have been educated or worked at Oxbridge – also highly unrepresentative.

It’s hardly a surprise then that one of JUSTICE’s two current interns not only attended the University of Oxford but already has two degrees. This, too, will probably not inspire confidence among any BAME candidate from a disadvantaged socio-economic background.

None of this would be especially troubling except for the fact that JUSTICE is a charity whose overarching purpose is to ‘promote the sound development and administration of the law for the benefit of the public.’

Moreover, JUSTICE states that its ‘Culture’ is ‘inclusive and collaborative’, and that it is ‘committed to recruiting staff from diverse personal and professional backgrounds’ (see below).

JUSTICE was founded in 1957, eight years before Britain’s first legislation to tackle racial discrimination: the Race Relations Act 1965. Legislation, case law, policy, research, and best practice has since improved racial representation at work. We know better what works and what doesn’t.

JUSTICE should know better. In 2017 it reported on the lack of diversity in the judiciary; unreflective of the society it serves. JUSTICE gave 3 reasons for diversity: legitimacy, quality and fairness – reasons that could apply to its own staffing.

Other reasons might be given for ensuring diversity. The national advice service Citizens Advice recognises ‘how issues impact on […] clients in different ways,’ adding ‘we need to make sure that the diversity of needs among our clients is taken into account.’

Another subtly different reason for diversity is based on the valuing of difference in background and experience. Examples of racial identity and experience informing legal practice can be seen in the recent autobiographies by Alexandra Wilson and Leslie Thomas QC.

There is a further much more prosaic but perhaps fundamentally important reason for eliminating the risk of bias in hiring: the Equality Act 2010 prohibits direct or indirect discrimination in hiring across nine protected characteristics, including race and gender.

Citizens Advice give another reason for ensuring diversity. It might well apply to JUSTICE: ‘We can expect that clients may be more likely to use our service if they can see themselves reflected in it, preferably at all levels of staff [and] trustees.’

JUSTICE’s work includes racial justice issues, so the diversity of its staff matters. On 25 February 2021, it published Tackling Racial Injustice: Children and the Youth Justice System. The same year, it published a report Reforming the Windrush Compensation Scheme.

JUSTICE also made a submission in 2020 to the government-appointed Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities. The submission addressed issues of racial disparity in the education and criminal justice systems, as well as judicial diversity.

JUSTICE states in relation to the posts: ‘We particularly welcome applications from Black and minority ethnic candidates, particularly those from socio-economically less advantaged backgrounds.’ More may be needed.

In October 2020, JUSTICE advertised its first Sir Henry Brooke Fellow post. Again, a full-time role for 6 months. The salary was £19,565 pro rata. JUSTICE stated: ‘We encourage candidates from “non-traditional” backgrounds to apply.’ It awarded the position to a white, Cambridge graduate.

In 2018, a JUSTICE Legal Fellow was another white, Cambridge graduate. None of this is to cast any aspersion on the individuals concerned, but it would also be concerning if JUSTICE doesn’t reduce the risk of bias in selection. It still requires names, and details of school/college/university attended.

Research shows that job applicants in Britain with white-sounding names are more likely to get a positive response from prospective employers than applicants with non-white-sounding names.

Details of candidates’ school/college/university might, unless removed at sift and long-/short-listing, allow bias to affect selection. So, some employers remove, at these stages of hiring, details of names and educational institutions in what is called ‘blind’ hiring.

JUSTICE clearly seek, as evidenced in the application form for these posts, to address socio-economic background and disadvantage. On pages 2 and 3 of the 12-page form, applicants are invited in five sections to provide details of any such background. But is this enough?

Most of JUSTICE’s fellows go on to positions in the legal profession. The profession is already disproportionately made up of those from the highest socio-economic class and by those who attended independent/fee-paying schools.

The Solicitors Regulation Authority latest survey (in 2021) of law firms shows that almost a quarter (23%) of all lawyers attended an independent/fee-paying school, which compares to a national average of 7.5% of the workforce attending an independent/fee-paying school.

The Bar Standards Board latest data (from 2021) on diversity among barristers in England and Wales also indicates that a disproportionately high proportion (19.3%) of barristers attended an independent school between the ages of 11-18.

I don’t wish this concern about the level and duration of paid employment, the staff profile, and any potential shortcomings in JUSTICE’s hiring to take away from what it does well elsewhere. Nor should it be overlooked that, like many other charities, it has been adversely affected by the pandemic.

According to its latest annual report (2020-21), it lost some funders, income decreased by just over 5%, and it ended the year with a small deficit (£15,159). It should also be noted that its fellow roles are externally funded. Funders vary from year to year. Linklaters are rich, others are not.

However, in view of JUSTICE’s status and reputation, its charitable objects, its previous work (especially on racial justice), and what we know works and doesn’t work in recruiting talent from disadvantaged socio-economic backgrounds, I wonder if it could do better.

Change is possible. In 2019, I raised concerns about the use of unpaid researchers at another legal charity, the Public Law Project, as this practice also inhibits social mobility, reinforces class privilege and contributes to inequality. Now, it no longer uses them.

In his latest book, The Return of Inequality: Social Change and the Weight of the Past, Professor Mike Savage, LSE, writes that ‘the weight of the past is returning, and along with this comes resurgent elitism, patronage, discrimination, and the entrenchment of inherited privilege.’

If jobs at legal charities which provide a stepping stone into the legal profession are not to contribute to such inequality, their salaries shouldn’t dissuade those from disadvantaged backgrounds, staff should reflect the wider population, and hiring should seek to exclude bias.

.

© Dermot Feenan 2022