An Illustration of who Benefits and who is Left Out or Marginalised from Organisation of an Academic Event

15-minute read

Dermot Feenan

LLB MA LLM Barrister-at-Law (non-practising) FRSA

.

An academic workshop scheduled to be held next month at a British university is a concerning illustration of white men dominating the organisation of an academic event.

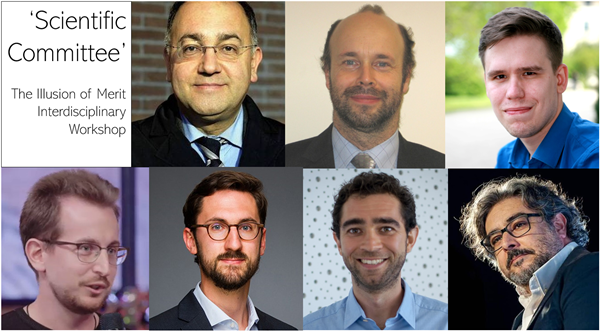

The seven-member ‘Scientific Committee’ (the organising committee of academics) and one of the ‘organising institutions’ (a five-member academic association) for the workshop are composed exclusively of white men. This is particularly ironic given the focus of the workshop.

The workshop, titled ‘The Illusion of Merit – Interdisciplinary Workshop’, is due to be held on 15 April at Cardiff University.

In this essay, I draw from the workshop’s Call for Papers [for non-academics: the public invitation to prospective presenters at the workshop to submit a brief outline to the workshop organisers]. That Call, issued in February 2021, is set out below.

The Call reveals troubling information about exclusion and marginalisation of women and minorities from the organisation of an academic event at a public institution in the United Kingdom which raises legal, policy and broader concerns.

Most significantly, the exclusively white, male composition of the seven-member organizing committee and of one of the organising institutions is inconsistent with: (a) the Public Sector Equality Duty placed statutorily on the host institution, Cardiff University, and on those individuals exercising public functions in organising the workshop, and (b) the institution’s policy on diversity and equality.

The exclusively white, male composition of this committee and of one of the organising institutions, drawn from the field of academic economics, is especially troubling given the well-documented concerns about male domination in that field of inquiry. I discuss these concerns with reference to a selection of the associated literature.

The exclusionary composition of the organising committee and of one of the organising institutions is not the only concern. Another of the organising institutions—a peer-reviewed international academic journal published by one of the largest academic publishers globally—is composed, at the editorial level, predominantly of white men from the Global North. The scope of the journal does not justify such narrow representation. Moreover, it is significant that the Editor-in-Chief of the journal is a member of both the organising committee and of one of the other aforementioned organising institutions. This should be of concern to the publisher of the journal, as I will explain shortly.

The narrow composition of the organising committee and of two of the organising institutions finds echoes in the absolute silence on gender, race, disability and social class in relation to merit in the Call for Papers, despite their extensive treatment in the scholarly literature.

These facts have a number of profound implications which go beyond compliance with law and policy on equality. These include the exclusion and marginalisation of people historically under-represented in academia, especially women and minorities, with corresponding impact on their opportunities for recruitment, retention and promotion in employment. The implications also include the risk of perpetuating narrow and exclusionary ways of thinking about the world. This matters not only for other academics but also for the public.

I now describe and examine the composition of the organising committee and organising institutions.

An exclusively male organising committee

The organising committee—which is somewhat pompously named, as certain men are wont to do, ‘Scientific Committee’—comprises seven individuals. All are white men.

They are Luigino Bruni, Huw Dixon, Karel Musilek, Vittorio Pelligra, Tommaso Reggiani, Rainer Michael Rilke, and Paolo Santori (also shown below, clockwise from title).

The complete dominance of men in the organising of the event is further reflected in the composition of one of the ‘organising institutions’ for the event.

Three institutions are listed as responsible for organising the event:

- Cardiff University – Cardiff Business School,

- HEIRS, and

- IREC: International Review of Economics.

‘HEIRS’ is also exclusively male.

An exclusively male organising institution

‘HEIRS’ stands for Happiness Economics and Interpersonal Relations. It is an all-male association of economists based in Italy, comprising:

Luigino Bruni————- LUMSA University, Rome

Luca Stanca—————University of Milan-Bicocca

Matteo Rizzolli————LUMSA University, Rome

Tommaso Reggiani——Cardiff University, Cardiff

Paolo Santori————-LUMSA University, Rome

Three of these men are members of the organising committee for the workshop: Luigino Bruni, Tommaso Reggiani, and Paolo Santori.

A picture has emerged of an exclusively male and white organising committee and organising institution of an academic workshop on a topic of broad social importance at a public university in the UK in the twenty-first century.

Turning to the composition of the another of the three organising institutions, the IREC, a similar picture emerges.

Another organising institution: predominantly white men from the Global North

The IREC, or, to give it its full name, International Review of Economics — Journal of Civil Economy, has one editor-in-chief. That is Luigino Bruni, named at the top of the list of members of the ‘Scientific Committee’ for the workshop and the team at HEIRS.

Bruni’s editorial assistant at the journal is Tommaso Reggiani, who—as has been noted—is also listed in the ‘Scientific Committee’ of the workshop and is also a member of HEIRS.

A lecturer in economics at Cardiff Business School, he came to the UK from Masaryk University in the Czech Republic in 2020.

Between 2015 and 2017, Reggiani was Assistant Professor at LUMSA University – the same university where Bruni is based.

The IREC lists 23 ‘associate editors’ and an 11-person ‘Advisory Board’. Two members of the ‘Advisory Board’ are dead, but as they were included in the listing they should be counted.

There are no women on the journal’s advisory board, and only 3 among the associate editors. Thus, of all those named (including the Editor and his assistant), only 8% are women.

Only one of those named is from the Global South. Of the 36 named persons none are Black or of Asian heritage. Professor Amartya Sen is the only person of colour listed. He fits within the elite profile of many of the others. He is Thomas W. Lamont University Professor, and Professor of Economics and Philosophy, at Harvard University, and was, until 2004, the Master of Trinity College, Cambridge. There is no-one else named in the journal from a minority ethnic background.

The dearth of scholars from the Global South risks reinforcing colonial and imperial ways of seeing which have been critiqued by, for example, Professor Boaventura de Sousa Santos in his book Epistemologies of the South: Justice Against Epistemicide (2007).

Such exclusions and marginalisation are also of concern especially in relation to women given the well-documented concerns about their under-representation in economics, as illustrated below (though the concern about exclusion and marginalisation extends to others, including with reference to race, disability, and social class).

Representation of women in economics

There are ongoing concerns about white, male domination in the field of economics (Harvey, 2019).

The Committee on the Status of Women in the Economics Profession (CSWEP) is a standing committee of the American Economic Association charged with promoting the careers and monitoring the progress of women economists in academia, government agencies and elsewhere. CSWEP has surveyed economics departments in US universities since 1972. In its latest survey (in 2020), it reported that while the proportion of women in economics departments has increased since the 1970s, three truths continue to hold for women in the academy:

- From entering PhD student to full professor, women have been and remain a minority

- Within the tenure track, from new PhD to full professor, the higher the rank, the lower the representation of women

- Compared with men, women disproportionately fall off the academic ladder at the time of promotion to tenured associate.

The Royal Economic Society, based in the UK but with over 4,000 members worldwide, is one of the oldest economic associations in the world, and it, too, is concerned about the lack of diversity in the discipline, including in under-representation of women. The Society’s Women’s Committee conducts an annual survey of gender representation in UK economics departments and research institutes. Its latest published report (for 2016) shows that women account for 28% of academic staff; and are more likely to hold precarious jobs and are less likely to hold senior positions than men. In its strategy for 2019-2023, the Society says it will place particular emphasis on promoting economics to women and girls, and others in under-represented groups.

Research on women in economics by Professor Shelly Lundberg and Dr Jenna Stearns (2019) indicated “that female economists face substantial barriers throughout their career”.

There are numerous explanations for this, including an unwelcoming culture that reinforces stereotypical beliefs of men as the in-group and women as an out-group. A survey of comments on a economics jobs discussion board based in the US, 2013 and 2017, found that postings about women tended to highlight physical appearance, personal information, and sexism, whereas those about men were more academically or professionally oriented (Wu, 2018).

Exclusion from an organising committee adversely affects opportunities to accumulate merit (cf. Burton, 1987). Membership of such a committee is likely to be relevant in recruitment, retention, and promotion. Such membership enhances visibility, status, and connections which may, in turn, improve other opportunities, such as participation in academic events, networks etc.

Lundberg and Stearns noted: “An accumulating body of evidence suggests that early-career female economists may be adversely affected by limited access to the mentoring and social networks that support research activities.” This evidence had accumulated for decades. It includes recognition from over a quarter of century ago of fewer support systems, with few role models or mentors, and little access to communication networks (Bagilhole, 1993).

Yet research shows that mentoring of junior female economics faculty by senior faculty increased the publication rates and grant funding of junior faculty, strengthening the argument that a lack of mentoring is important for women (Blau, Currie, Croson, and Ginther, 2010).

McDowell et al (2006) found in their study of networks and co-authorship among academic economists that networks impact the joint decision to publish and co-author and that these effects differ by gender.

Women’s participation in organisation can also affect gender representation in conference programmes. A study by Chari and Goldsmith-Pinkham (2017) of the representation of female economists in selected conference programmes in the USA found that when a woman organizes the programme, the share of female presenting authors and discussants is higher.

Exclusion or marginalisation may be a red flag for future discrimination. De Paola and Scoppa (2015) found that equally productive female economists in Italy are less likely to be promoted when the promotion committee is composed exclusively of males, with the gender gap disappearing when women are evaluated by a mixed-gender committee.

The exclusion or marginalisation of women from the organisation of an academic workshop can also affect the production and scope of knowledge: narrowing the issues addressed, the questions asked, the experiences allowed, and the frameworks of analysis.

Professor Lorraine Code noted in relation to women and knowledge in her landmark 1991 book What Can She Know? Feminist Theory and the Construction of Knowledge: “institutionalized disciplines that produce knowledge about women, and position women in societies according to the knowledge they produce, are informed by versions of and variations on the methods and objectives that received epistemologies authorize.” Similar considerations come into play with racialised, classed or dis-abled standpoints.

The involvement of the journal in this workshop should be of concern to the journal’s publisher, Springer Nature. Shortly, I will explain why. First, I address the most serious issues – the failure of a number of the organising institutions and members of the organising committee to adhere to the Public Sector Equality Duty and institutional policy on equality. I then examine why the Call for Papers also provides cause for concern.

Host institution’s and organisers’ duty regarding equality

Law

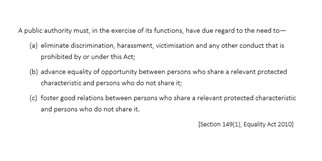

Universities are public authorities for the purpose of equality legislation. In England and Wales, the relevant law is found in the Equality Act 2010. Public authorities are subject to the Public Sector Equality Duty in section 149(1) of the Act.

Universities must, in exercise of their functions, have due regard to the need to, amongst other things, advance equality of opportunity between those who share a relevant protected characteristic and those who do not.

The legislation defines the ‘relevant protected characteristics’ as: age; disability; gender reassignment; pregnancy and maternity; race; religion or belief; sex; sexual orientation.

The legislation also sets out what it means to have due regard to the need to advance equality of opportunity between those who share a relevant protected characteristic and persons who do not. It means having due regard, in particular, to the need to:

(a) remove or minimise disadvantages suffered by persons who share a relevant protected characteristic that are connected to that characteristic;

(b) take steps to meet the needs of persons who share a relevant protected characteristic that are different from the needs of persons who do not share it;

(c) encourage persons who share a relevant protected characteristic to participate in public life or in any other activity in which participation by such persons is disproportionately low.

A workshop whose seven-member ‘Scientific Committee’ consists of white men only, whose organising institutions together comprise almost exclusively white men, which is on a concept that is evidently of interest to women and others who have, or could reasonably be expected to have, an academic interest, perhaps also alongside personal investment based on life experience, in the concept, yet where women make up only 22% of those cited in the Call for Papers hardly encourages women and prospective participants from a Black, Asian or Minority Ethnic (BAME) background to participate in public life or an activity in which participation is disproportionately low.

Cardiff University ultimately bears the responsibility for this workshop. It is the host institution. It is one of the specified organizing institutions; with its logo, and that of its Business School, on the Call for Papers.

The contact person for the workshop (Tommaso Reggiani) is a member of academic staff at the University. He is also on the ‘Scientific Committee’ for the workshop, alongside two other members of academic staff. One of these (Huw Dixon) is a professor, the highest academic rank in the British university system. All of them will or should have undergone at the university equality and diversity training, which should have included reference to equality law.

Given that the workshop bears the name of the university and its Business School it is also certainly the case that the workshop will have had to receive approval from a senior manager on behalf of the University. Ordinarily, requests for such support will require sufficient details about the workshop, including who is organising the event—here, the Scientific Committee—and an outline of the event—here, the Call or something like a Call.

The individuals at the University who made the decision to support the workshop and/or to participate in organising the workshop are exercising public functions. They are subject to the Public Sector Equality Duty. Subsection 2 of section 149 of the Equality Act states: ‘A person who is not a public authority but who exercises public functions must, in the exercise of those functions, have due regard to the matters mentioned in subsection (1).’

The workshop is open to a wide range of people. The Call is addressed specifically to “economists, historians, theologians, philosophers, scholars in organization and management and other social scientists”. This population necessarily includes those who will hold posts in public institutions. Registration to the workshop will be open to the public.

Cardiff University, its Business School, and those individuals exercising public functions in the organization of the event are in breach of the spirit—if not, as relevant, the letter—of equality law at a key stage in the organization of this workshop.

Policy

Cardiff Business School states: “We are committed to supporting, developing and promoting equality and diversity in all our practices and activities.”

Cardiff Business School also acknowledges its statutory duties: on a webpage titled ‘Equality and diversity’. But those of us who have experience of actual discrimination and who fight for equality in universities know only too well that too often these statements are window dressing, box-ticking exercises.

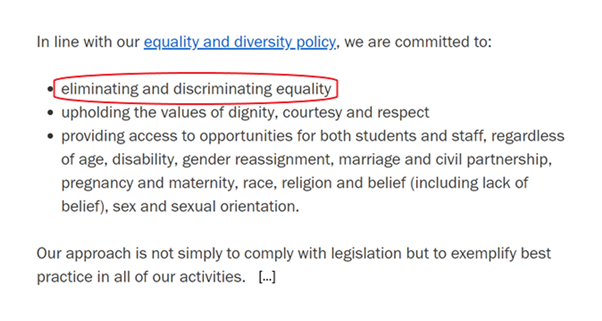

It is perhaps no surprise, therefore, that on the Cardiff Business School website there is this garbled nonsense about how the School will secure equality and diversity: “eliminating and discriminating equality” (below). How is it possible that a university can produce such meaningless gibberish?

It’s difficult to avoid the conclusion that it is because equality and diversity doesn’t really matter to the Business School. It’s also no surprise that it is a co-organiser of a workshop on merit, the broader organisation of which is also at odds with the university’s statutory duties and its own policy.

This is not simply a deficiency by a public authority, it also reflects on those members of staff responsible at Cardiff for this state of affairs: Tommaso Reggiano, Huw Dixon (also a member of the School’s senior management team), and any other member of management that sign off on such proposals.

The gender composition of the organising committee of the workshop is also inconsistent with the commitments that Cardiff University Business School makes under the Athena Swan Charter on gender equality in higher education and research, especially to advance gender equality and to address unequal gender representation. It is also perhaps unsurprising, then, that women make up less than 17% of the senior management team in the Business School.

In view of these concerns, I am sharing this essay with senior managers at Cardiff University.

Having established that aspects of the organization of the workshop are inconsistent with law and policy, I now return to concerns about the Call for Papers and its likely effect on the narrowing of academic inquiry.

Call for Papers: Silence on Race, Disability, Social Class and Gender

The Call cites 29 scholarly works, including books and articles. Some of these are co-authored or, in the case of collections, co-edited. The total number of cited authors is 49, of which 78% are men, 22% women.

The Call quotes 3 authors. Two are men. They are Thomas Piketty (2020) and Amartya Sen (2000).

The Call makes no reference to race, disability, social class, or gender – significant characteristics for any analysis of ‘merit’. Yet, these characteristics have featured in the scholarly literature; specifically on merit and race (e.g. Samson, 2013; de Souza and Dias, 2018; and Warikoo, 2016) and merit and disability (e.g. Hunt, 1991; Selden, 2000; and Young, 2007).

The scholarly literature on merit also refers explicitly to social class (e.g. Breen and Goldthorpe, 2001; Rivera, 2015; and Muzatti and Samarco’s, 2006, edited collection on class, identity and working class experience in academe – especially Part I) and gender (e.g. Castilla, 2012; Thornton, 2007).

None of these characteristics are mentioned explicitly in the Call. This is despite the fact that some of the articles cited in the Call themselves refer explicitly to a number of these variables. Jennifer Laird, one of the authors cited in the Call, found in her research on employment in the US public sector after the recession in 2007-2008 a double disadvantage for Black public sector workers: concentrated in the shrinking economy and more likely than white and Hispanic public sector workers to experience job loss. She refers over a dozen times to race. Similarly, an article by Professor Paul Piff and others, which is cited in the Call, refers to ‘race’ 18 times in the substance of the article. Moreover, the title of the article by Piff and others specifically refers to social class.

There are few persons of colour cited in the Call, yet many of those I cite are from racial or ethnic minorities. Many others from racial or ethnic minorities who have researched and published on merit could be added, such as Professor Lani Guinier (2015).

I now turn to explain why the narrow composition of the workshop and of one of the organising institutions is likely to be of concern to Springer Nature, the publisher of the journal which is another of the organising institutions for the workshop.

Concerns for Springer Nature, publisher of the IREC

In December 2019, Springer Nature announced a new ‘diversity commitment’ for its research publishing.

Springer Nature states: “supporting diversity and inclusion both within our own organisation and in how we work with the wider research community, is extremely important to us.” The commitment notes that “there has been broad recognition for some time that equal, diverse and inclusive environments can improve research outcomes”. Springer Nature adds, “we feel we have a duty to do more to actively address diversity in research and to support others in doing so.”

Springer Nature refer to their ‘commitment to diversity’. The announcement is couched largely in the future tense. Springer Nature states, for instance: ‘We will be taking action to improve diversity and inclusion in the conferences we organise, and in our commissioned content, the peer review population and editorial boards.’ However, the announcement does also set out steps already taken, including in reference to publishing and invitations to event speakers: “Editors are asked to intentionally and proactively reach out to women researchers when commissioning externally-authored content, recruiting peer reviews, or inviting event speakers.”

The announcement concludes with a section headed ‘Diverse representation at conferences and a new code of conduct’. In this section, Springer Nature refers to a new diversity and code of conduct policy.

The policy sets out expectations about diversity within the organising committees and speakers at Nature Conferences – a series of conferences organised in conjunction with the publisher’s flagship science journal Nature. The policy commits Springer Nature to monitor and report on diversity at those conferences. In addition, the policy sets out appropriate conduct expectations and includes a process for reporting harassment or other unacceptable behaviour.

The expectations regarding diversity include “having no male-only organising committees for all new Nature Conferences” and having an “equal percentage of women and men as speakers”. Springer Nature go on to say in their announcement: “Naturally, we recognise that diversity goes beyond gender. We ask our conference co-organisers to consider other aspects of diversity, such as geography, ethnicity, culture, and career-stage, among others.”

While the policy applies presently only to Nature Conferences, Springer Nature state that it will apply to all Springer Nature scholarly events.

It is unclear whether the IREC’s involvement in ‘The Illusion of Merit – Interdisciplinary Workshop’ is technically named a ‘Springer Nature scholarly event’. However, the involvement of a Springer Nature journal in this workshop surely falls within the spirit of the publisher’s diversity policy. For this reason, I am drawing this essay about the workshop to the attention of Steven Inchcoombe, Chief Publishing and Solutions Officer, and a Member of the Management Board, Springer Nature, who was a co-author to Springer Nature’s announcement regarding diversity, and Alison Mitchell, Chief Journals Officer, Springer Nature.

There is a broader context for concerns with the exclusively white, male composition of the organising committee and of one of the organising institutions of the workshop, the preponderance of white men from the Global North in the supporting journal, and the absence of any explicit reference to race, disability, social class and gender in the Call.

There has been a shift to the right in many countries which is associated with retrenchment of regressive gender hierarchies, intolerance of gender differences, heteronormativity, ethnonationalism, denial of structural or systemic discrimination and injustice, and the demonisation of contemporary movements for racial equity and justice. There has been an increased awareness of ongoing racial injustice which was accelerated by the killing in 2020 of George Floyd in the US and the subsequent second wave of Black Lives Matter protests globally. Against this context, the persistence of such large exclusively white, male groups in the organisation of academic events at public institutions is of grave concern.

The composition of an all-male, all-white seven-member organising committee for such an event might even be regarded as an ‘inequality practice’ (borrowing from Van den Brink et al’s, 2012, concept of ‘gender inequality practice’) that disadvantages women and BAME academics.

Conclusion

In this essay, I drew attention to the exclusively white, male composition of a seven-member organising committee and of one of the organising institutions (HEIRS: a five-member academic association) of a planned academic workshop in the UK. I identified problems with this composition and the preponderance of white men from the Global North in the editorial board of a supporting journal among the organising institutions for the workshop. I explained why these problems appear to be echoed in the absence of any explicit reference to race, disability, social class, and gender in the Call for Papers for the workshop. The exclusion and marginalisation of women and minorities matters as an issue of compliance with equality and non-discrimination law and policy (whether or not inequality or discrimination is intended). It matters especially because of historical exclusion and marginalisation in academic economics, particularly as this is well-documented in relation to women’s under-representation. It matters because representation across characteristics such as a gender, race, social class, and disability not only ensures participation by those in the population who should be entitled to participate and are available to do so, but because such participation will likely bring different approaches which enhance and expand knowledge. These considerations are especially important for an interdisciplinary conference on merit, a topic which has rightly attracted considerable critique for its tendency to exclude and marginalise. In publishing this essay on an open access basis and in drawing the problems about the workshop to the attention of relevant parties, such as senior managers at Cardiff University and senior employees at the publisher Springer Nature, I continue a praxis that combines socially engaged, scholarly research with a commitment to inclusive, effective and practical action, especially in the sector —academia— in which I have spent much of my working life.

_______________________

This essay is dedicated to the memory of my mother, who passed away 24 February 2021, and to women everywhere seeking equality and equity for themselves and others.

.

© Dermot Feenan 2021