30-minute read

Dermot Feenan

LLB MA LLM Barrister-at-Law FRSA

[Links to endnotes are not currently working. Hyperlinks to these references will, where available, be added in due course. In the meantime, all notes must be checked manually. Apologies for this inconvenience.]

1. Introduction

This complaint is made with reference to The Ofcom Broadcasting Code, January 2019, (‘the Code’), Ofcom Procedures for investigating breaches of content standards for television and radio, 3 April 2017, Ofcom Guidance Notes;[1] and applicable law, including the Communications Act 2003 (as amended), the Human Rights Act 1998, and (as set out in the Schedule) the Equality Act 2010, the European Convention on Human Rights (in particular Articles 10 and 14), and International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination.

2. Summary of complaint

The Dispatches programme ‘The Truth About Traveller Crime’ breached the following sections of the Broadcasting Code:

Section Two: Harm and Offence, Rule 2.1 and Rule 2.3.

Section Three: Crime, Disorder, Hatred and Abuse, Rule 3.1.

Section Five: Due Impartiality and Due Accuracy and Undue Prominence of Views and Opinions, Rule 5.1.

The complaint addresses each breach in turn.

3. Section Two: Harm and Offence

The relevant principle in this section states:

To ensure that generally accepted standards are applied to the content of television and radio services so as to provide adequate protection for members of the public from the inclusion in such services of harmful and/ or offensive material.

Rule 2.1 provides:

Generally accepted standards must be applied to the contents of television and radio services and BBC ODPS so as to provide adequate protection for members of the public from the inclusion in such services of harmful and/or offensive material. (emphasis added)

Rule 2.3 provides:

In applying generally accepted standards broadcasters must ensure that material which may cause offence is justified by the context (see meaning of “context” below). Such material may include, but is not limited to, offensive language, violence, sex, sexual violence, humiliation, distress, violation of human dignity, discriminatory treatment or language (for example on the grounds of age, disability, gender reassignment, pregnancy and maternity, race, religion or belief, sex and sexual orientation, and marriage and civil partnership). (emphasis added)

The content of Section 2 as whole makes clear that reference in Rule 2.3 to “material which may cause offence” refers to both “harmful and/or offensive material” in Rule 2.1. Rule 2.3 states that “material which may cause offence is justified by the context (see meaning of “context” below).” That ‘Meaning of “context”’ states that context includes (but is not limited to) eight bulleted points, including: “the degree of harm or offence likely to be caused by the inclusion of any particular sort of material in programmes generally or programmes of a particular description”. It makes no sense to treat those points as limited only to offensive material. They must apply to harmful and/or offensive material. Ofcom applied a number of those points in its decision on harm in finding a breach of Rule 2.1 in respect of the complaint about London Real: Covid-19.[2]

This complaint submits that the programme subjected Travellers to harmful and offensive material through a number of stereotypes, namely that Travellers are (a) criminal and tend towards criminality and/or are aggressive, and (b) are lawless.

Travellers are a ‘race’ according to law (as elaborated below).

This complaint takes the stereotyping of Travellers in the programme as a violation of both Rule 2.1 and Rule 2.3, and that such stereotyping amounts to a violation of human dignity and discriminatory treatment or language on the grounds of race.

3.1 Travellers as a group covered by ‘race’

The programme addressed Travellers.

Section 9(1) of the Equality Act 2010 provides that ‘race’ includes:

(b) nationality;

(c) ethnic or national origins.

Section 9(4) of the Act provides: “The fact that a racial group comprises two or more distinct racial groups does not prevent it from constituting a particular racial group.”

In O’Leary and others v Allied Domecq and others (2000) the court held that Irish Travellers are a distinct racial group by reason of their ethnic origins for the purpose of the Race Relations Act.[3] It is believed that Irish Travellers (Mincéir) travelled to England from Ireland in the nineteenth century (around the ‘Great Famine’, in the latter half of the 1840s) and in greater numbers from 1960 onwards. Research indicates that Irish Travellers’ distinct ethnicity can be traced back to the Irish Rebellion of 1641. Scottish Travellers were recognised as a racial group for the purpose of equality legislation in 2008.[4] Romany Gypsies were legally recognised as a racial group in Commission for Racial Equality v Dutton in 1989.[5] It is believed that Romany Gypsies trace their arrival in Britain from India in the 1500s.[6] In Northern Ireland, the Irish Traveller community is specifically protected as a racial group under the Race Relations (Northern Ireland) Order 1997, Article 5(3)(a).

The following section provides brief explanation of why discriminatory language is both a violation under Rule 2.1 and Rule 2.3.

3.2 Discriminatory treatment or language

The Code refers to ‘discriminatory treatment or language’. The Code is not a statute. It does not require for its meaning the application of rules of statutory interpretation. The concept of ‘discriminatory treatment or language’ is broad. It is not limited in the precise and narrow way set out in the statutory definition of direct discrimination in section 13 of the Equality Act 2010: “A person (A) discriminates against another (B) if, because of a protected characteristic, A treats B less favourably than A treats or would treat others” or even the definition of indirect discrimination in the Act. The phrase “discriminatory treatment or language” may be assisted by case law on that concept but cannot be limited by that case law.

Discriminatory treatment or language may include portrayal of Travellers which stereotypes them or unfairly distinguishes them from other ethnic groups, including through a process of othering – addressed in the subsection below.

Since the introduction of the Race Relations Act in Britain and subsequent laws and policies on racial discrimination, racial discrimination is less likely to be overt not simply because it is more widely known to be unlawful but because it is much more likely to be regarded as socially unacceptable. Racial discrimination, when it does occur, can take more subtle forms, including an insinuation about an ethnic group or a purported association between an ethnic group and a negative behaviour.

Ofcom’s own research now shows that viewers and listeners are increasingly concerned about discriminatory – especially racially discriminatory – content against specific groups than other offensive content, such as nudity and swearing.[7]

The programme ‘The Truth About Traveller Crime” engages in a number of forms of discriminatory treatment or language. The stereotyping of Travellers is both harmful and offensive and amounts to discriminatory language or treatment.

Othering

The stereotyping of Travellers was also reinforced through a process of ‘othering’ Travellers. While there are variants in the uses and forms of othering, it generally consists in a differentiation between at least two groups through which the ‘othered’ group is rendered, relatively, inferior.[8] It can involve the conceptualisation of a people or group as intrinsically different from oneself; as a result of which they are excluded. [9] Research shows how Travellers are othered in numerous ways. [10] Othering can lead to Travellers being racialised, for instance, as a ‘pariah’ group[11] or as “the enemy of the ‘normal’ settled community.”[12]

The othering of Travellers in ‘The Truth About Traveller Crime’ occurs in a number of ways, principally:

Counterposing of Travellers (and Traveller sites) as distinct from ‘locals’ (e.g. at 15:26 minutes), ‘residents’ (e.g. at 21:39 minutes; 29:35 minutes) and ‘the community’ (e.g. at 6:18—6:20 minutes).

Counterposing of Travellers (and Traveller sites) as incompatible with ‘pleasant’, ‘quiet’, ‘peaceful’ English ‘rural’ life (from 2:21 minutes in the programme, accentuated by the use of agreeable guitar music – in contrast to the ominous/ foreboding music used in discussing Travellers).

These are serious social harms, that have profound adverse material effects on Traveller individuals, families, communities, groups and Travellers as a people.[13]

3.3 Harm and harmful material

The programme causes harm to Travellers by using and reinforcing long-standing, harmful stereotypes of Travellers. Such stereotypes are centuries old. They are implicated in systemic disadvantages for Travellers which are reflected in restrictions on movement and housing, discrimination in access to goods and services, hate crime, and higher indicators of deprivation – including in education and health – than for the sedentary population.[14] Such stereotypes in turn reinforce discrimination, including prejudice or bias against, or abuse of, Travellers.

Each of these stereotypes is addressed in sequence, with some background information to help make sense of the way in which the stereotypes in the programme derive power from this long history of discrimination and abuse of Travellers. Ofcom has previously considered ‘cultural context’ in deciding Rule 2.3.[15]

3.3.(a) Stereotype: Travellers as criminal or tending to criminality

3.3.(a)(i) Background

The stereotyping of Travellers as criminal or tending to criminality is well-documented,[16] and is consistent with stereotyping of other racial and ethnic minority groups.[17]

In their report on policing and Gypsies, Roma and Travellers, 71% of police officers interviewed identified unconscious bias and/or discriminatory and racist behaviour towards Gypsies, Roma and Travellers (GRT) by the police.[18] One police officer admitted: “The whole emphasis has been one of criminality, of looking at Gypsies and Travellers as some sort of deviant criminal group, and that’s been reinforced my whole career.” [19] One female Irish Traveller interviewed in the research recounted being asked by a male police officer, “why are the majority of Gypsies and Travellers criminals?”[20]

In 2015, The Traveller Movement complained to the Metropolitan Police about online racist posts in a Facebook group by serving officers. The posts included: “I fucking hate p*keys” and “You know when they are lying … their lips move.” The Metropolitan Police rejected the complaints. The Traveller Movement appealed to the Independent Police Complaints Commission, which upheld the complaint. The Commission recommended that the Metropolitan Police hold misconduct meetings … for potentially breaching standards of professional behaviour in relation to authority, respect and courtesy, equality and diversity, and challenging inappropriate behaviour.” [21] The Independent Office for Police Complaints, which was replaced by the Independent Office for Police Conduct on 8 January 2018, found that police officers who were members of the Kent Police Gypsy Liaison Team should have cases to answer for gross misconduct after entering a property unlawfully and being disrespectful to the occupants.[22] It is significant that The Traveller Movement argued in their report on policing that Gypsy Traveller Liaison Officer roles, which typically focus on enforcement, reinforce negative stereotypes by inextricably linking Gypsies/ Travellers with criminality.

Such stereotyping is evident in the population. A 2017 survey of 2,174 thousand adults carried out between 29th September – 2nd October 2017 reported that when asked “what first comes to mind when you think of a Gypsy/Traveller” the majority responded with negative words, such as “thief”, “criminal”, “dirty” and “p***y”.[23]

Courts have on a number of occasions found racial discrimination against Irish Travellers and awarded compensation for injury to feelings. In 2015, J D Wetherspoons pub was found to have discriminated, contrary to the Equality Act 2010, in refusing entry in 2011 to a group that comprised Irish Travellers and those accompanying them. The judge said that the decision by the pub was “suffused with the stereotypical assumption that Irish Travellers and English Gypsies cause disorder wherever they go. In my judgment this is a racial stereotyping of those with that ethnic origin. It can be reduced to this crude proposition; whenever Irish Travellers and English Gypsies go to public houses violent disorder is inevitable because that is how they behave.” [24] In May 2015, the pub chain settled a second case when three Irish Travellers who were refused entry to one of its pubs in Cambridge brought proceedings for racial discrimination.[25]

3.3.(a)(ii) Evidence in the programme

The programme engages in stereotyping of Travellers in a number of ways.

The title and anchoring question

The title of the programme (‘The Truth About Traveller Crime’) and the anchoring question in the programme (“what is the truth about Travellers and crime”) make clear that the programme intends to set out a comprehensive, infallible account of Travellers.

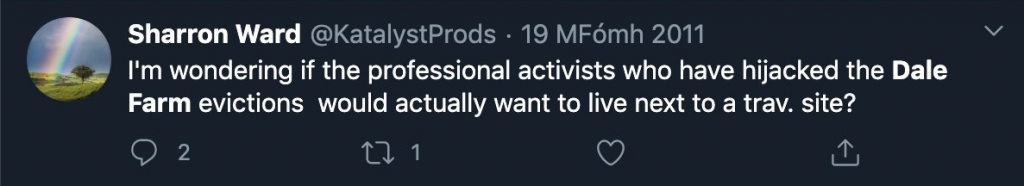

The title reinforces the stereotype of Travellers as criminal or tending towards criminality. Marc Willers QC referred to the title as “dog whistle” (below) – defined by Ian Osalov as “a phrase that may sound innocuous to some people, but which also communicates something more insidious either to a subset of the audience or outside of the audience’s conscious awareness — a covert appeal to some noxious set of views.”[26]

Christina Newland, a writer, went further; describing the programme title as “race-baiting trash”

Ellie Mulcahy, Head of Research at The Centre for Education and Youth, who has researched on GRT, wrote: “The title alone does damage”.

The word ‘truth’ is defined in the Oxford English Dictionary as “something that conforms with fact or reality” (II), and – when prefixed with ‘the’ – “[t]he fact or facts; the actual state of the case; the matter, situation, or circumstance as it really is” (7.a).[27] The antonyms for ‘truth’ are “falseness, falsity, untruth”, with near antonyms including: “inaccuracy, incorrectness, inexactitude.”[28] The components of the definition, specifically, ‘fact’ and reality’ also mean that truth cannot be based on opinion or a narrative that deviates from the actual situation. The use of the word ‘truth’ in the title of the programme carries epistemological responsibility, requiring a duty not only to present fact and reality but to avoid, among others, inexactitude or inaccuracy.

The framing of the programme as presenting ‘the truth’ was repeated in the description of the programme as “the truth behind stories of criminality and lawlessness”.

The programme selectively uses information – as will be explained in this complaint – to ostensibly present ‘the truth’. In fact, the programme is inaccurate in multiple ways in its account of Travellers. It depends upon insufficient data to make generalisations about Travellers. It engages in distortion to imply that Travellers engage in crime. In the words of Lord Simon Woolley, it does so “to demonise and vilify the whole Traveller community”.[29]

A number of police sources have criticised the programme for lack of accuracy and balance, and the adverse effects this will have for Travellers.

The British Transport Police Diversity networks wrote on 17 April that the programme was “not a balanced or accurate depiction and forgets that GRT communities are disproportionately more likely to be subjected to hate crime.”

Janette McCormick, Deputy Chief Constable College of Policing, Programme Director National Uplift Programme, National Police Chiefs’ Council Lead for Gypsies and Travellers and Disabilities, wrote that there was “no evidence that links higher crime levels to Traveller sites, nor do [the National Police Chiefs’ Council] have ‘no go’ sites.”[30] Deputy Chief Constable McCormick added: “Stereotyping a whole race on individual cases drives prejudice.”

Waterside Police in Hampshire, responding to Chief Constable McCormick’s tweet, wrote the following in a thread:

In their final tweet in that thread they added: ‘There is no place for #Racism or #Discrimination”.

The concept of ‘Traveller crime’

There is no such thing as ‘Traveller crime’. There is crime. There are crimes.

All sorts of people commit crimes, including young/old; black/ white; poor/ rich.

There are no crimes that pertain only to Travellers, though some laws have been targeted directly at GRT people and some continue to have a disproportionate impact on GRT people.

Statement at 15:18 minutes

The presenter of the programme claims: “so far our investigation has uncovered high crime levels around several Traveller sites” (emphasis added).

Examples of offences provided are variously either single incidents or anecdotal/ hearsay accounts – manslaughter, assault, intimidation, ‘modern-day’ slavery, theft, cruelty to animals, hare coursing, and criminal damage.

The programme does not – up to the statement at 15:18 minutes – provide a transparent, random sample of crimes by which it would be possible to make a reliable, valid judgement about crime ‘around’ Traveller sites. All of these crimes might be found ‘around’ many other population areas, including villages, towns, housing estates, or industrial complexes.

Moreover, not only is no compelling evidence presented that links ‘high crime levels’ with those sites but the programme presents a statement from Leicestershire Police (the police force area in which one site – Mere Lane – is extensively featured), which states: “Overall crime rates in the immediate area surrounding the site have fallen over the last couple of years.” The only information supporting the purported “high crime levels around several Traveller sites” are the programme’s own assertion (at 1:44 minutes) “[t]here is an association between the presence of a Traveller site and a crime rate increase or a higher crime rate” and a tenuous statement from an unidentified individual who is described as a police officer who claims (between 1:34—1:37 minutes, repeated at 45:46—45:49 minutes): “There is a disproportionate level of crime committed by Travellers.”

It is possible to find a high level of offending by selectively choosing any population area, for instance, a housing estate where an organised crime unit has become established or an industrial complex with serial violations of environmental, health and safety, or HMRC-related offences. This does not, nor should it, necessarily imply that housing estates or industrial complexes are linked to high crime – but the message that Traveller sites are so associated is conveyed in the programme.

Statement at 15:32 minutes

The presenter states that they [the production team] have sampled “30 Traveller and Gypsy sites where issues of crime and anti-social behaviour have been reported. Then we received the recorded crime figures for a 1-mile radius around these postcodes over a 12-month period. Around 70% of sites we found the crime rate was above the national average. Around 47% of sites we found the crime rate was at least a third above”. The presenter does not explain how these sites have been selected, which is a key requirement for statistical reliability.

It is also clear that the programme is relying on two separate spatial identifiers, ‘Traveller site’ and ‘postcode’, which may be distinctive and lead to a skewed framework for analysing data. There are over one-and-a-half million postcodes in use in the United Kingdom, and while each postcode covers an average of about 15 households, in reality it can be anywhere between 1 and 100 households.

Recall that this programme purports to tell ‘the truth about Traveller crime”. If the choice of those sites involved selection bias or a skewed framework this would undermine, if not invalidate, any such finding – though there are additional reasons why the analysis is unreliable to support the purported “truth about Traveller crime”.

Irish Travellers may move between the island of Ireland and Britain (and further afield). Travellers generally (if we take that term to include Romany Gypsies, Welsh Travellers, Scottish Travellers, Roma, ‘New Age’ Travellers, and Showpeople) may also travel throughout parts of Britain (and potentially further afield). No evidence is presented from Ireland, Northern Ireland, Scotland, and England and Wales – which would be necessary for a population that is mobile and which might reveal significant variables in crime rate between different legal jurisdictions.

The category of ‘Traveller’ is never defined in the programme, yet the programme claims to present the truth about ‘Traveller crime’.

The programme also switches across categories of analysis: ‘Travellers’/ ‘Irish Travellers’/ ‘Traveller sites’/ ‘travelling community’. Each of these categories are profoundly demographically different. The same category must be used consistently in measurement to proceed with valid statistical analysis. This is not the case in the programme.

Travellers live in varied and distinctive forms of accommodation: Local authority residential Gypsy/Traveller sites; Local authority Transit sites; Private, commercial residential Gypsy/Traveller sites owned and managed by a non-local authority body; Owner-occupied sites, owned by the Gypsy/Traveller family/ies living on it; Permanent housing (house/ flat), and; on the roadside or in another unauthorised encampment. No mention is made of these various forms of accommodation. Gross, stereotypical generalisations are made about ‘Travellers’ absent any reference to a highly significant variable—accommodation type. There is an apparent lack of awareness in the programme that the majority of Travellers now live in housing.

It is unclear from the programme how the concept of ‘site’ was defined.

According to latest government statistics, in July 2019, in England the total number of traveller caravans is 23,125.[31]

Many Gypsies, Travellers and Irish Travellers now live in settled accommodation and do not travel, or do not travel all of the time, but nonetheless consider travelling to be part of their identity. At the 2011 Census, the majority (76%) in England and Wales lived in bricks-and-mortar accommodation, and 24% lived in a caravan or other mobile or temporary structure.

It is clear at 18:24 minutes in the programme that a series of crimes are listed. These are:

- Anti-social behaviour

- Burglary

- Robbery

- Vehicle crime

- Violent crime

- Shoplifting

- Drugs

- Criminal damage and arson

- Other theft

- Other crimes

- Bike theft

- Theft from Person

- Weapons

- Public Order

Certain offence categories are omitted, including assault, sexual offences, hate crime, tax evasion, and corporate and regulatory crime. Recording of sexual offending appears to be much lower among Travellers than among the settled population. Travellers also experience high levels of abuse, as shown below in this complaint. This abuse may amount to hate crime – yet it is entirely omitted from analysis of crime statistics in the programme. Corporate and regulatory crime is also likely to be low among Travellers for obvious reasons: most working Travellers are self-employed, but there is also a high rate of unemployment. Nonetheless, the programme claims high crime rates among Travellers.

There is well-documented evidence in the public domain of the under-representation of Travellers as victims of crime. One chief inspector interviewed for The Traveller Movement report on policing said: “The under-representation of GRT people as victims of crime is something we are working hard to try and address, particularly hate crime. We know that hate crime is underreported in general and even more so with Gypsy Traveller communities because that confidence in policing isn’t there.”[32] The report noted that all police officers interviewed described Gypsy, Roma and Traveller individuals as less likely to report being victims of crime than the rest of the population.

In their joint submission to the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Elimination of All Forms of Racism, Friends Families Travellers & National Federation of Gypsy Liaison Groups stated: “hate crimes and hate incidents are not being effectively monitored and there are no robust statistics available about the extent of this problem.” [33]

The presenter makes only fleeting, inadequate reference to crime against Travellers – very late in the programme, filmed at night and against the same ominous music to convey a sense of fear that has been used throughout the programme to link Travellers with crime. She states: “Travellers are often the victims of crime, too” (between 46:12—46:14 minutes). This insufficient reference in ‘The Truth about Traveller Crime’ to crime against Travellers and the reasons for such under-reporting represents a grave omission in the evidence base necessary to reasonably consider crime and Travellers, and further undermines the credibility of the programme.

There is also no consideration to fact that the some of the unverified anecdotal and hearsay accounts of crimes and anti-social behaviour purportedly by Travellers may be driven by stereotypes and other prejudicial views. Such accounts may also emanate from some police. In 2018, the Traveller Movement reported on findings which “indicated the presence of systemic discrimination against GRT communities within police forces” in England. [34]

Moreover, there appears to be no evidence that the production team have validly analysed offences across different key categories, including those triable on indictment and those triable summarily.

The offence categories chosen appear to have been deliberately selected, rather than randomly sampled – suggesting potential confirmation bias.

Statement at 40:08 minutes

The presenter states very late in the programme that the team had conducted a “random” sample of 237 “Traveller and Gypsy sites from across England.”

The presenter states that “crime is a problem area around a significant minority of those sites” (emphasis added).

The presenter proceeds: “In 56% of cases, the crime rate was below the national average and around 30% of sites the crime rate was at least a third lower than the national average. But on the other hand, we also found that around 27% of sites the crime rate was at least a third above the national average. In simple terms, serious crime problems were associated with over a quarter of sites.”

The data from this random sample shows that around the majority of Traveller sites in England for those crimes which are selected, crime is lower than the national average.

It is unclear what crimes have been selected, and this is highly relevant to the analysis and conclusion.

The presenter’s reference to data on crimes around 27% of Traveller sites being above the national average cannot reliably be used to reach valid conclusions about Travellers generally. In statistics, the average is the number that measures the central tendency of a given set of numbers. There are different averages, including but not limited to: mean, median, mode and range. A concentration of particular types of crime around several Traveller sites may explain these data but they cannot reliably describe “Traveller crime”.

The programme mentions one site, Enderby. Yet, in 2019 it was reported that 25 families on that site were to receive enforcement notices to leave because they were not Travellers. The programme conflates ‘site’ automatically, and invalidly, with ‘Traveller’.[35]

There are a number of fundamental problems with the statistical analyses: how crime is defined, which offences were selected (and omitted), how ‘site’ is defined, how ‘Traveller’ is defined (and which groups have been excluded), how initial sites were chosen, how ‘averages’ calibrated to percentages distort complete data.

The Office for National Statistics shows that the City of London has the highest crime rate in England and Wales.[36] This is not because we can associate City workers with crime, still less posit a notion of ‘City Worker Crime’. Rather, the area is London’s traditional financial district, and its population swells by 56 times during working hours, which appears to explain the extremely high crime rate given the area’s small residential population.

Despite these problems in the use of statistics in the programme, the programme uses the concept of ‘association’ between ‘Travellers’ or ‘Traveller sites’ (and on some occasions the ‘Travelling community’) and ‘crime rate’; implying that Travellers are criminal or tend to criminality.

The concept of ‘association’ in its technical, statistical sense is different from the concept of causation. This distinction is not made clear in the programme. Moreover, there is no analysis of the statistical concept of ‘correlation’. Postulating an ‘association’ where variables in the sample are vague, unrepresentative, and open to external influences (which are normally corrected using ‘controls’) renders the findings at best questionable and at worst virtually useless. This is particularly the case where the causes of crime, its policing, prosecution and conviction are multi-variate.

There are no quantitative data on Gypsy and Traveller patterns of offending.[37]

Recent research indicates that income inequality is the most consistent structural correlate of rates for theft and other forms of property crime. All forms of theft tend to occur disproportionately in poor, isolated, socially disadvantaged neighbourhoods.[38] This was not adequately investigated in the programme.

Paul Bradshaw, Course Leader of the MA in Data Journalism at Birmingham City University, has now incorporated reference to flaws in the methodology used in the Dispatches programme in his publication ‘A journalist’s guide to cognitive bias (and how to avoid it)’.[39] He states in his blog: “This episode of @c4dispatches should be used to warn journalists what happens when you don’t take steps to prevent confirmation bias or out-group homogeneity bias in your reporting.”

Moreover, the Ministry of Justice does not record crime systematically with reference to Traveller ethnicity. Five categories of ethnicity have been used: Asian; Black; Mixed; Other including Chinese, and; White.[40] While category ‘White – Gypsy or Irish Traveller’ was introduced into the 2011 Census, this category may not be used in reliably recording crime for a number of reasons, As the Ministry of Justice notes in its latest report on statistics on race and the criminal justice system:

Collecting data on ethnic groups is complicated, because of the subjective, multifaceted and changing nature of ethnic identification. There is no consensus on what constitutes an ethnic group, and membership is viewed as self-defined and subjective to the individual. An ethnic group can encompass common ancestry, shared heritage and elements of culture, identity, religion, language and physical appearance.[41]

Moreover, two sources of ethnicity data may arise: officer-identified and self-identified. The Ministry of Justice, notes that ethnicity using PNC data “may not always be reliable” because the “ethnicity of the defendant may have been wrongly recorded by a police officer or administrator”.[42]

The programme purports to tell ‘the truth’ about Traveller crime, yet it is also woefully avoidant of issues of representativeness of data vis-à-vis the population of Travellers in United Kingdom – which would be important for any reliable analysis of Travellers and offending.

In addition to the flawed statistics, the programme relies on very limited highly sensational cases – many of which involve Irish Travellers – where individuals were ultimately sanctioned: Patrick Doran and his family, and three men responsible for a cashpoint robberies in a number of towns and villages in England.

The 2011 Census for the first time included a Gypsy/Traveller/Irish Traveller category for Britain.[43] For Northern Ireland, ‘Irish Traveller’ is collected under its own ethnic group. In Scotland, the category was ‘Gypsy/Traveller’. In total, around 63,000 people identified themselves in these groups. 57,680 respondents identified as being a Gypsy/Traveller/Irish Traveller in England and Wales.

This may be a significant undercount because many Gypsies, Travellers and Irish Travellers do not identify their ethnicity due fear of racism and discrimination. The Traveller Movement estimates a population of around 120,000 in England.[44]

The Cabinet Office’s Race Disparity Audit revealed the inconsistencies in categories used (e.g. Education data has a separate category for Irish Traveller, but it previously combined ‘Roma’ and ‘Romany Gypsy’ in one category). The Audit also revealed inconsistencies in the extent of inclusion because data on Gypsies, Travellers and Roma is, at best, partial in health, employment and Criminal Justice System monitoring systems.

Hare coursing

A significant section of the programme focuses on hare coursing. The section attempts to associate Travellers with hare coursing – a criminal activity – and place this criminal activity within the programme’s overall stereotyping of Travellers as criminal or tending towards criminality.

Before analysing how the programme does so, some background information on hare coursing is necessary.

According to the Report of Committee of Inquiry into Hunting with Dogs in England & Wales in 2000, hare coursing has a long history, going back to the Egyptian and Greek empires, and was introduced to Britain by the Romans.[45]

Hare coursing was practised for sport, food or pest control for significant periods of time among the aristocracy and landed gentry. The first published rules on hare coursing in England were reputedly drawn up by Thomas Howard, 4th Duke of Norfolk, a member of the English aristocracy, in the reign of Elizabeth I. Coursing clubs were subsequently established throughout England, with the first in Swaffham in 1776. The National Coursing Club was founded in 1858. The club organised the three-day annual coursing event The Waterloo Cup from 1836 to 2005. The event was founded and supported by The 2nd Earl of Sefton, a member of the aristocracy. The event attracted regular early support from the British upper classes, including Sir St George Gore, 8th Baronet; The 5th Earl of Lowther; Sir Robert Jardine, 2nd Baronet, and; Charles Brownlow, 2nd Baron Lurgan. Lord Lurgan’s greyhound became a household name following three wins in 1868, 1869 and 1871, and the commendation of Queen Victoria. It was only in the late 19th century that hare coursing became predominantly working-class sport. Hare coursing was not banned in England and Wales until the Hunting Act 2004.

Hare coursing continues elsewhere, including in Portugal, Spain and parts of the Western United States, as a lawful, regulated sport. Other activities which involve hunting and/ or killing animals, birds or fish for sport, such as pheasant shooting, remain legal in the United Kingdom. And, while fox hunting is banned, many police forces do not enforce the law. According to a former head of the national wildlife crime unit, foxhunting has been continuing with impunity across the UK with police and courts failing to hold those organising and taking part in them accountable.[46] The League Against Cruel Sports collected witness reports of 485 incidents of suspected illegal foxhunting between October 2019 and early March 2020, including of 38 foxes killed and 15 suspected killings of foxes.[47]

Prosecutions for hare coursing in recent years are low relative to other offences and have been declining. According to the latest data on prosecutions and convictions for hare coursing from 2013 through 2018 in England and Wales:[48] there were 11 prosecutions in 2013 for attending an event. This fell to 3 in 2014. There were no such prosecutions in 2015, 2016, 2017 or 2018. Across the six-year period for which data are available, there were slightly higher figures for participating in a hare coursing event – which includes permitting land to be used for the purpose of an event or permitting a dog to participate in an event. There were 12 such prosecutions in 2013, falling away through 8 in 2015 to 1 in 2017. There was no prosecution for any such offence in 2018. There were no convictions for either attending or participating in hare coursing in 2016 through 2018.

Notwithstanding, the programme states at 10:08 minutes: “Rural areas are especially affected by Traveller crime. Farmers say they are on the frontline of a rural crime wave and much is down to one specific illegal activity – the blood sport of hare coursing, banned by law since 2005.”

As the presenter says this, the programme cuts to a clip of a hare being pursued in a field by a dog. A male Irish accent can be heard off camera. The programme thereby reinforces the stereotype of Irish Travellers as engaging in criminal behaviour.

No further reference is made to ethnicity of perpetrators.

However, the programme switches to footage of a police vehicle driving quickly, blue lights flashing. The camera then features the presenter in the vehicle, who adds: “So, at the moment we’re en route to a hare coursing incident with three men and dogs out on the fields chasing hares.” The filming proceeds within the vehicle, with the presenter stating: “Cambridgeshire Police received more than 1,400 reports of hare coursing last year.” The camera features the driver talking on his intercom, stating: “It’s that vehicle to your right Pete. Nah, looks like a pick-up.” The presenter then adds: “And we’re being invited on patrol with a specialist unit set up to tackle hare coursing and other rural crime.” The camera returns to the driver, as the vehicle pulls up to a halt. He states: “Not hare coursing then.” Throughout this segment, the programme played similar ominous music that had been used against other segments of the programme which profiled Travellers.

The next part of this section features footage of a police chase along country roads and a field, which led to the conviction of Nelson Hedges. Mr Hedges was suspected of being involved in hare coursing. The programme does not mention that Mr Hedges is from Guildford Road, Guildford, Surrey, and runs a company called ‘Hedges Roofing’. This information is publicly available. Mr Hedges ethnicity is not publicly available information. We are not informed by the programme that he is or is not a Traveller. The inclusion of his case implies that he is a Traveller, not least because the section then proceeds to feature the ‘specialist unit’ on call out to a suspected burglary, at which point the presenter states: “So, they’re suspected from a local Traveller community.”

In the course of the section on hare coursing, only one identifier of ethnicity has been used: an Irish accent. There is then footage of a mobile police crime unit ultimately detecting no hare coursing, a profile of a man whose ethnicity is unknown, and culmination in conjecture that suspected burglars come from “a local Travelling community”.

The use of the initial footage of the police crime unit in these circumstances is unethical and adds nothing of value to any investigative reporting. It tends to reinforce the only implied ethnic identifier (Irish Traveller) and the subsequent conjecture about ‘a local Travelling community’ with the stereotype that Travellers, especially Irish Travellers, are criminal or tend towards criminality.

Moreover, the presentation of film footage of what we are led to believe are Travellers engaging in hare coursing without reference to official statistics on prosecutions and convictions, including of no convictions across both offences for the last three years, is deeply misleading.

Channel 4’s Factual Programme Guidelines state: “Channel 4 has a bond of trust with its audience and a duty to ensure that viewers are not deceived or misled by our programmes. Ofcom will not hesitate to impose the most serious sanctions, including substantial fines, for failure to ensure that programmes are accurate and truthful or where viewer trust is breached.”[49]

None of the foregoing seeks to justify hare coursing, but the selection and manner of presentation of hare coursing in a programme titled ‘The Truth about Traveller Crime’ in view of the foregoing information raises at the very least serious questions about the impartiality of the programme and could reasonably be seen to suggest racial prejudice.

3.3.(b) Stereotype: Irish Travellers – criminal/ tending towards criminality and/or aggression

The programme title refers to ‘Travellers’. Throughout the reference to Travellers is undifferentiated; save where (a) specific reference is made to Irish Travellers either explicitly by the presenter or in showing footage of Irish Travellers, or (b) reference is made to “Gypsy/ Traveller sites”. On a number of occasions the presenter makes reference to “the Travelling community” (including at 14:27—14:29 minutes; 42:54 minutes; 44:23 minutes). The term ‘Travelling community’ is used in legislation in Ireland to refer specifically to Irish Travellers.[50] The phrase will be understood by many to refer to Irish Travellers.

Indicative evidence of this understanding can be seen in a comment to a review of the programme in The Daily Telegraph.[51] Tom Fox writes: “The lot of them should be deported back to Ireland.”

This is no aberrant understanding. Another person, ‘Rayles C’, who comments on the review refers (incorrectly) to the “1948 arrangement”, which is in fact the Common Travel Area arrangement between Ireland and the United Kingdom, and states that it should be “rescinded” and “those here forcibly removed”:

It is a matter of concern that the programme does not differentiate clearly between distinct groups, given that some people will understand the term ‘Travellers’ to refer to Irish Travellers, Scottish Travellers, the Welsh Kale, English Romanichal/ Romany Gypsies, and Roma. There are important differences between these groups. It is especially troubling that in a programme that purports to be about the ‘truth’ of Travellers no such distinctions are made. The programme maintains an unfair ambiguity in using this term. This maintained ambiguity might allow ill-informed individuals to view the programme as referring to all of these groups – despite their distinctions – which is why there has been widespread public condemnation of the programme by representatives of each distinctive group and individual members of those distinctive groups. However, the same lack of explicit differentiation allows a more subtle message to be communicated by the programme, alongside other audio-visual cues: that the ‘Travellers’ referred to are in fact ‘Irish Travellers’. Thus, the programme can be seen to apply the stereotype of criminal or tending towards criminality to the distinct Irish ethnic group: Irish Travellers. This stereotyping can draw from broader historical stereotyping of the Irish as criminal or tending towards criminality, but also disorderly, dangerous, aggressive or violent.[52] The programme conveys this message in a number of ways.

In the first minute and 13 seconds of the programme, there are four audio clips; each of men with Irish accents. The first shows a man in a maintained, grassed area with caravans. He says, “we’re not going anywhere.” The second is of a group of men around a caravan, with one man heard saying in an Irish accent, “I’m coming for you, come out and fight”. The third is of two males fighting in a shop, with a man saying off camera in an Irish accent: “That’s it there, Pat.” The fourth is of Paddy Doherty, an Irish Traveller, saying to camera: “Drugs has destroyed Travellers”.

These clips are interspersed with other footage referring to Travellers being “at the centre of a number of headline-grabbing crimes”. These clips are followed by two further clips: first, of an unidentified male dropping a petrol pump by a car at a filling station and then quickly making to jump into the driver’s seat of the vehicle, and, secondly, of another unidentified man entering a caravan. Neither of these latter two clips are accompanied by any explanations of what the individuals are doing. Their interpolation into the overall sequence of clips will, however, likely leave viewers believing that these are Irish Travellers engaged in criminal behaviour. This belief is likely to reinforced by brooding background music, and a narration by the presenter that has the effect of linking the images with crime. This is effected at two key points in this initial sequence of images.

At 53 seconds into the programme, the presenter – having referred to “headline-grabbing crimes” says: “In this film, Dispatches is going to confront an uncomfortable question – what is the truth about Travellers and crime?” The question is asked precisely at the point when the programme shows the footage of the man with the Irish accent saying, “We’re not going nowhere.” Shortly afterwards, the presenter asks the question: “What is the truth?” As she reaches the end of the question, stopping with the word “crime”, the programme shows the two males punching each other in a shop, with a male voice off camera saying “That’s it there, Pat.” The clips of males with Irish accents fighting also reinforces the stereotype of Irish aggression and violence.

The Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) found Channel 4 in breach of its Code in 2012 for posters advertising one of its programmes My Big Fat Gypsy Wedding (Channel 4 Television Corporation, 3 October 2012).[53] The posters bore the slogan: “BIGGER. FATTER. GYPSIER.” The ASA ruled that one poster featured a young boy with his lips pursed in a manner that “was likely to be seen as aggressive”. The ASA said that shown with the word “Gypsier”, this might suggest that aggressive behaviour was typical of younger members of the Gypsy and Traveller community and reinforced negative cultural stereotypes. The ASA concluded: “We considered that implication was likely to cause serious offence to some members of those communities, while endorsing the prejudicial view that young gypsies and travellers were aggressive.”

The Dispatches programme subsequently makes explicit reference to Irish Travellers. First, in reference to a Traveller site ‘Mere Lane’ in Leicestershire. The presenter states (at 2:59 minutes): “most of the community there are Irish Travellers.” The presenter does not explain why it is deemed necessary to refer to the ethnicity of the residents at this site, and there appears to be no justification for doing so. The effect is to associate Irish Travellers with the programme’s profile of residents at the site as being engaged in criminal behaviour. This occurs between 2:40—2:52 minutes into the film when the presenter states: “People there say they have been victims for years of ongoing crime and anti-social behaviour which they say is coming from the local Traveller site.”

The linking of Irish Travellers with criminality is further effected by the programme in showing two further clips of males with Irish accents. First, a clip of what is described as hare coursing. The first clip is introduced with the following words (between 10:13—10:29 minutes): “Farmers say they are on the frontline of a rural crime wave and much is down to one specific illegal activity: the blood sport of hare coursing, banned by law since 2005.” Just after the presenter states “one specific illegal activity” the programme shows a clip of a dog chasing a hare, a male with an Irish accent can be heard off camera, saying, amongst other things, “she let her go again, boys”.

The second clip (starting at 26:35 minutes) is, again, of a grassy area with caravans. We hear a male Irish accent. The camera then pans to the man, in a close verbal exchange with a police officer who is with another officer. The man leans in towards the officer and speaks loudly towards him. He is not deferential. This clip, like the earlier clips, is accompanied by distinctive foreboding music. The clip is shown without accompanying verbal or textual explanation. This clip follows immediately upon a short segment of the programme in which Andrew Selous, MP for South West Bedfordshire, speaks about Traveller sites as “ungoverned space” (which Popp, tellingly, misquotes as “ungovernable”). The implication is that the site and this man represents ungovernability, lawlessness – a further stereotype which harms Travellers.

The placing of the footage directly after this segment without break, tends also to reinforce an idea of Travellers as lawless – another stereotype which is further addressed below.

Paddy Doherty, an Irish Traveller, is interviewed in the programme. Mr Doherty is not a representative of any Traveller organisation. He is a ‘celebrity’, who came to prominence in Channel 4’s My Big Fat Gypsy Wedding – which programme was subject to a complaint from the representative organisation The Traveller Movement to Ofcom for breach of the Broadcasting Code. Pauline Anderson OBE, who is introduced as an Irish Traveller and as Chair of the Trustees of The Traveller Movement, is interviewed in the programme but she subsequently raised concerns about the programme and the basis for her participation (see further, below).

When the term ‘travelling community’ is used by Anja Popp it is with reference to criminal behaviour. In a segment of the programme in which Popp is shown travelling in a vehicle with members of Cambridgeshire Police’s Rural Crime Team, an officer receives a call of two young suspects to a burglary running from the scene. Popp states: “So, they’re suspected from a local travelling community”. There is no information which would justify associating the suspects with a ‘travelling community’.

3.3.(c) Evidence of harmful effects on Travellers – the need for counter-definition

It is telling that in the wake of the programme many Irish Travellers posted messages on social media with the hashtag #AfterDispatches stating that they were ‘not a criminal’. The following starting with one by Chelsea McDonagh, an MA student at King’s College London, and ‘Pavee’ (Irish Traveller), are illustrative:

However, in keeping with the observation earlier in this complaint; it is clear that the programme was also seen to harm Romany Gypsies and Roma. Katie Roberts, a Romany Gypsy, posted a similar tweet with the hashtag #AfterDispatches announcing she is “NOT a criminal”.

3.3.(d) Stereotype: Traveller sites/ Travelling community as lawless[54]

A further stereotype in the programme is of Travellers as lawless.

The programme used the language of lawlessness of Travellers in its description of the programme, stating, in part, “Anja Popp looks at the truth behind stories of criminality and lawlessness.”

This notion of lawlessness is specifically used by Popp in the programme.

In discussing one Traveller site, Mere Lane, Leicestershire, she states (between 8:20—8:26 mins):

“some of the locals feel that the police have allowed the site to become a lawless, no-go place.” (emphasis added)

Yet, Popp then quotes Leicestershire Police, who state:

“Officers visit the Mere Lane site […] regularly.”

Popp repeats the idea of Traveller sites as lawless places later in the programme (at 18:08 mins):

“During our investigation we’ve heard a common complaint: that some Traveller sites have become lawless places where crime and anti-social behaviour go unpunished and the feeling is that police are failing to investigate properly.” (emphasis added)

Popp does not name those sites. She does not identify the source(s) or even whether there is more than one source and if so the number of the purported complaints. She does not provide any independent verification of such complaint. In fact, the programme presents abundant evidence – which is detailed below – that sites are not lawless but are in fact subject to the law and are policed.

The stereotype of lawlessness is reinforced by Popp in a leading question to an interviewee (between 21:30—21:36 mins):

“Doesn’t that just mean that people from the Travelling community can commit crime knowing full well that they’ll get away with it?”

The question is doubly revealing, implying not only lawlessness but extending this idea from the site or sites to the ‘Travelling community’ generally.

The stereotype of lawlessness is repeated soon after when Popp states (at 21:39 mins):

“We’ve spoken with some residents in different areas of the UK who think there’s a two-tier legal system in which they have to follow one set of laws and the Travelling community follow a different set and the police don’t enforce those laws on the Travelling community.”

In fact, Popp has shown in the programme that Travellers are not beyond the law. She had presented a number of clips which showed police engaging with some Travellers, carrying out investigations on some Travellers, and referring to prosecution of some Travellers which led to their conviction and imprisonment. The claim by Popp to have spoken with “some residents in different areas of the UK” appears to be exaggerated as there is no evidence that she spoke to anyone in Scotland or Northern Ireland. The only person she appears to have spoken to in Wales is Irish Traveller Paddy Doherty but, as shown earlier, we may reasonably infer that Doherty does not fall within Popp’s definition of ‘resident’ – so it would seem that Popp (or her team) has in fact spoken only with some residents in some parts of England. Popp’s leading question is evidence of prejudice which I return to below with reference to Section Five of the Code.

The stereotype of lawlessness is also evident in the following exchange in her interview with Andrew Selous, MP for South West Bedfordshire.

Popp: You described some areas of your constituency as ungovernable.

Selous: Well, I think the phrase used was “ungoverned space” which was actually a term used of Afghanistan during the Taliban era […] I stand by it because Traveller sites can be out of sight, out of mind.

The distinction between ‘ungovernable’ and ‘ungoverned space’ is telling. Not only does it show that Popp has not accurately presented what Selous previously said (which is publicly available)[55] – raising issues about due accuracy which I return to below with reference to Section Five – but it implies that Traveller sites are by their nature lawless rather than the more limited – though still questionable – claim by Selous that they have previously not been governed.

Moreover, Popp does not challenge the claim by Selous that Traveller sites are “ungoverned spaces”, despite previously presenting evidence of sites which had been visited by police. In fact, as Selous ends his statement (at approximately 26:35 minutes), the programme fades away from the interview to show, against a return of the foreboding music, footage of a maintained grassland area with caravans and then an Irish accent before panning to a man in a verbal exchange with a police officer who is accompanied by another officer.

Later in the programme, Popp refers to police ‘incident logs’ for 4 Traveller sites in Bedfordshire which detail “three years of why Bedfordshire Police were called out to four Traveller sites.” Popp then refers to “multiple accounts”. Popp also refers to specific sites: Greenacres, Toddbury Farm, and Stables. A cursory examination of publicly available news online shows that police have been called out to these sites. This is not mentioned by Popp.

In summary, the stereotype of Traveller sites as lawless is pervasive throughout this programme. It is stated by Popp, and indeed extended by her to the Travelling community generally. It goes unchallenged when implied by Andrew Selous MP despite clear evidence in the programme and available publicly elsewhere that Traveller sites, and the Travelling community, are not ‘lawless’.

3.3.(e) Violation of human dignity

There is evidence that the programme was deemed to violate the dignity of Travellers (and others concerned about the portrayal of Travellers). This evidence includes the following:

Lord Simon Woolley, a former Commissioner of the Equality and Human Rights Commission, said what the programme did was to “trash” the desire of Traveller and Roma groups to “belong to wider society with their pride, culture and dignity intact”, further divide communities, and “set Travellers equality back a long way” (emphasis added).

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights proclaims that all human beings are born free and in equal dignity. This is recognised in the Preamble to the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination. The use of stereotyping in the programme is a form of racial discrimination which undermines that dignity.

3.3.(f) Offensiveness

It was stated at the outset of this complaint that stereotypes of Travellers can be both harmful and offensive. Abundant evidence has been set out above of such adverse effect. Further evidence of offensiveness includes the following indicative tweet posted about Travellers in response to broadcast of the programme.

The first refers to Travellers as “absolute filth” and “[a]bsolutely scum”.

Such responses flow directly from the programme. They represent some of the worst forms of offensive stereotyping: classic dehumanisation of Travellers in associating them with ‘filth’ – a racist trope which has been well-documented in relation to Jews and others.

Research conducted into Irish Travellers in prison in 2011 found stereotypes offensive:

Some Traveller prisoners felt that the acceptability of terms such as ‘paddy’ and persistent allusions to stereotypes of Irish people as intellectually inferior, unpredictable and drunken were offensive. One prisoner made the point that constant talk by prison officers which depicted Irish people as alcoholics might be acceptable in certain circumstances but that in prison, when one could not respond for fear of incurring punishment, such stereotypes had a demoralising effect on prisoners from an Irish background.[56]

3.4 Context

The Code explains under the heading ‘Meaning of “context”’ that context includes (but is not limited to), inter alia:

Taking a number of these in turn (because others which are duplicate across sections are addressed elsewhere in this complaint):

The editorial content of the programme, programmes or series

The programme was part of a series called ‘Dispatches’ on Channel 4. Dispatches describes itself “Channel 4’s award-winning investigative current affairs programme”. Dispatches first broadcast on 30 October 1987.

The programme in issue was titled “The Truth about Traveller Crime”.

Much has been made above about the programme’s repetition of stereotypes of Travellers. These stereotypes were also reinforced through a series of techniques, including use of ominous/ foreboding music; filming at night and in spaces which suggest danger; and editing cuts which showed images and/or footage which reinforced stereotyping, including against ostensibly neutral questions from the presenter.

Music or sound accompaniment in a broadcast has also informed Ofcom’s consideration of breach of Rule 2.3.[57]

The music played at key points in the programme tended to reinforce the portrayal of Travellers as potentially dangerous. The music was described as “menacing” by Mark Quinn, a solicitor, in tweet referring to the programme generally as “[a]bsolutely disgraceful reporting”:

John Connors, an award-winning Irish Traveller director, actor and screenwriter noted that the programme was anti-Traveller “propaganda” evident from the editing decisions in the early minutes of the programme: “dark music, flashing images, violence”.[58]

These techniques also undermine the “due impartiality” requirement in Section Five of the Code and in Ofcom’s guidance.

Ofcom’s Guidance Notes on Section 2: Harm and offence state:

“Research suggests that viewers and listeners appreciate programmes that are representative of the diverse society in which they live. If there is an underrepresentation, the use of stereotypes and caricatures or the discussion of difficult or controversial issues involving that community may be seen as offensive in that it is viewed as creating a false impression of that minority.” (p. 6)

The underrepresentation of Travellers in the programme, and the consequent absence of individuals and groups engaged in lawful, civic-minded activity tends also to have the effect of aggravating the programme’s stereotyping of Travellers as criminal or tending towards criminality.

The format of this programme was a formal investigative documentary. It was not informal. It was not a news item responding in real time to fast-moving developments. It was planned and edited for broadcast in a pre-arranged format. Heightened responsibility flows from this.

The service on which the material is broadcast

The programme was first broadcast on Channel 4. It was thereafter made available on Channel 4’s ‘All 4’ on-demand service’ for a period of up to 29 days after broadcast.

The time of broadcast

The programme was broadcast at 9.00pm, peak viewing time. The fact that the programme was available on ‘All 4’ for several weeks after must also be taken into consideration.

The degree of harm or offence likely to be caused by the inclusion of any particular sort of material in programmes generally or programmes of a particular description

The degree of harm and offence was not only likely to be caused to Travellers (and Romany Gypsies and Roma) but has caused harm and offence to Travellers. Evidence has been set out above of the actual and potential harm to Travellers by the programme from stereotyping. The degree of harm is significant. The degrees of offence is significant.

There is also mounting evidence that Travellers’ have communicated that the programme harmed them. For example, the All Party Parliamentary Group for Gypsies, Travellers and Roma raised its concerns with Channel 4, noting that “[v]ery many Gypsies and Travellers have come forward to express their shock, anger and fear as a direct result” of the programme.[59]

Helen Jones, CEO of Leeds GATE, an organisation led by Gypsy and Traveller people in partnership with others in and across West Yorkshire, wrote the day after the programme: “My phone didn’t stop ringing, whatsapping, messaging last night. So many people in shock, telling me again about hate crimes that resulted from the last hate fuelled broadcast against our communities. I’m wondering if we should be grateful for lockdown? No arson attack on the office as a result this time. So far.”[60]

On 18 April, Leeds GATE sent the following tweet stating: “We are hearing so much distress from our members following the @C4Dispatches programme. If you are feeling targeted call the office for a ring back”

GATE Hertfordshire posted a week after the programme and referring to the “hurtful hateful comments the GRT communities have had to endure over the last week”:

A number of Travellers referred to harm or anxiety about harm.

Chelsea McDonagh, a Traveller who is studying for an MA at King’s College London, wrote after watching the programme: “I’m sick of worrying about whether this stuff will affect my future chances”:

Concerns about harm were shared after the programme aired by others who understood that ‘Travellers’ could include them (such as Romany Gypsies).

Dr Geraldine Lee-Treweek, who has Romani heritage and is Head of Department of the School of Social Sciences at Birmingham City University, wrote that it was a programme “that actually harms us”.

Violet Cannon, who is a Gypsy and a CEO, wrote similarly:

There were scores of similar tweets from members of the Gypsy, Roma and Travelling people, including:

Davie Donaldson, student:

Lisa Smith, journalist:

Sherrie Romany Smith, florist: https://twitter.com/SherrieSmithGRT/status/1251003689847926785?s=20

Ruby Smith, journalist:

Scarlett Smith, student:

Numerous other personal testimonies of harm are contained within a video produced by London Gypsy Traveller:

The reference to harm in Section Three of the Code should also include harm the programme does to the work that has been achieved in improving relations between Travellers and the settled population in recent years.

Lord Simon Woolley, a former Commissioner of the Equality and Human Rights Commission, said what the programme did was to “trash” the desire of Traveller and Roma groups to “belong to wider society with their pride, culture and dignity intact”, further divide communities, and “set Travellers equality back a long way”. These are serious social harms, that have profound adverse material effects on Traveller individuals, families, communities, groups and Travellers as a people.[61]

The likelihood of harm and offence must be understood within the pre-existing context of long-standing discrimination against GRT people. This is further indicated in the comments of Professor Liz Yardley, Professor of Criminology, Birmingham City University, who was interviewed in the programme. Replying to a tweet from Paul Bradshaw on problems with the methods used in the programme, she wrote that the programme “has done so much damage already to an already marginalized community”. She referred also to the programme’s misrepresentation and stigmatization of Travellers.

Given the history of stereotyping against Travellers which has led to discrimination, abuse and violence, concerns have been raised by human rights organisations, such as Amnesty International[62] and The Equality and Human Rights Commission, about media representation of Travellers. Guidelines exist for the media on how to approach issues pertaining to Travellers. The programme did not adhere to these guidelines.

The Equality and Human Rights Commission (Scotland) produced a resource for the media, including a checklist for “balanced reporting on issues relating to Gypsy Travellers”.[63] The first eight of ten points in the checklist are:

1. Be aware of material that is likely to lead to hatred or discrimination

2. Remember that most readers or viewers have no direct contact with Gypsy Travellers and base their opinions on what they see in the media

3. Be aware of stereotypes

4. Be clear whether you are reporting fact or someone else’s opinion.

5. Do not assume or suggest that the actions or beliefs of any individuals reflect a whole group, community or race.

6. Do not sensationalise or exaggerate issues involving Gypsy Travellers.

7. Seek to balance the reporting of specific ‘incidents’ (e.g. unauthorised encampments) with wider coverage and background to some of the causal factors around accommodation that Gypsy Travellers face.

8. Gypsy Travellers are not ‘outsiders’. They are full citizens of Great Britain and Ireland.

This complaint is made cognizant of the broadcaster’s right to freedom of expression and the audience’s right to receive information and ideas as set out in Article 10.

A decision that the broadcaster has breached Rules in the Code does not infringe either of those rights.

The European Court of Human Rights noted in Vejdeland v Sweden[64] (2012): “Restrictions on freedom of expression must […] be permissible in instances where the aim of the speech is to degrade, insult or incite hatred against persons or a class of person” [46]. Such restrictions are permissible with reference to race.

‘The Truth about Traveller Crime’ programme was materially different from the televised broadcast in Jersild v. Denmark[65] in which the European Court of Human Rights decided there had been a violation of Article 10 of the Convention as a result of the conviction of a journalist for the offence of publishing a statement insulting or degrading a group of persons on account of their race. The journalist had produced an item in a “serious television programme” reporting on racist views among a group of Danish youth. ‘The Truth about Traveller Crime’ did not merely, as in Jersild, introduce the programme with reference to recent public discussion and press comments” on a “matter” of “great public concern”[66], constitute a “news programme”[67] which “sought – by means of an interview – to expose, analyse and explain this particular group of youths, limited and frustrated by their social situation, with criminal records and violent attitudes”[68] in which the interviewer “clearly dissociated him[self] from the persons interviewed.”[69]

In D.H. and Others v. the Czech Republic [GC], 2007, 182, the European Court of Human Rights stressed in relation to discrimination against Gypsies and Roma people that as a result of their turbulent history and constant uprooting, they have become a specific type of disadvantaged and vulnerable minority. The Court confirmed that special consideration should be given to their needs and their different lifestyle both in the relevant regulatory framework and in reaching decisions in particular cases [ 181](see also Connors v United Kingdom, 2004, [84]). Travellers are in an analogous position.

It is insufficient for the presenter to state, as she does, “issues around crime from a specific community is obviously always going to be very difficult and sensitive to talk about” (at 3:46 minutes). The difficulty and sensitivity of doing so does not relieve the programme of otherwise complying with the Code.

The likely size and composition of the potential audience and likely expectation of the audience

The audience was likely to be large given the time of broadcast (including the fact it was broadcast during the so-called coronavirus ‘lockdown’), the sensationalist title of—and promotional information about—the programme, and coverage of the programme in the media (including but not limited to the The Daily Telegraph and the Daily Mail online).

Promotional information about the programme included a trailer and tweets.

In summary, the context of the programme was such that despite its self-description as an “investigative current affairs programme” and brief gestures towards contextualising crime rates, there were serious flaws in its methodology and its ability to offer sufficient and effective counter-balancing contributions, the overwhelming effect of which was to engage in a long-standing stereotype associating Travellers with crime and/or a tendency to criminality/ aggression and lawlessness. This effect is further evidenced in relation to Section Three of the Code.

4. Section Three: Crime, Disorder, Hatred and Abuse

Principle:

To ensure that material likely to encourage or incite the commission of crime or to lead to disorder is not included in television […]

Rule 3.1 provides:

Material likely to encourage or incite the commission of crime or to lead to disorder must not be included in television […]

The Code explains in the Note to Rule 3.1, that “material” may include but is not limited to, inter alia: “hate speech which is likely to encourage criminal activity or lead to disorder.”

The Code states:

Significant contextual factors under Rule 3.1 may include (but are not limited to):

• the editorial purpose of the programme;

• the status or position of anyone featured in the material; and/or

• whether sufficient challenge is provided to the material.

For example, there may be greater potential for material to encourage or incite the commission of crime if a programme sets out to influence the audience on a subject or theme, or provides an uncritical platform for an authoritative figure to advocate criminal activity or disorder.

There may be less potential for a breach of Rule 3.1 if opposing viewpoints and sufficient challenge are provided to people or organisations who advocate criminal activity or disorder, or where a programme seeks to provide an examination of or commentary on criminal activity or disorder in the public interest.

Other examples of contextual factors are provided in Ofcom’s guidance to this Section of the Code.

The Code does not require that material does in fact encourage or incite such crime or lead to disorder: it is enough if it was likely to do so.

There is significant evidence that the programme did encourage hatred.

4.1 Hatred

‘Catika’ wrote above the hashtag #Dispatches shortly after the programme started: “I absolutely despise travellers […] most are animal abusing [sic] scumbags. I fucking hate the thick twats.”

Daniel Chapman, noted the programme and wrote of Travellers: “Disgusting people”

Mike Thomas replied to Daniel Chapman, writing that the army should “shell them”:

Joseph Finlay believed the programme amounted to incitement to racial hatred:

Welsh Kale wrote that the programme had the “objective of arousing racist rage in their audience”:

Christina Kerrigan, who describes herself as from a “Traveller background” wrote after the programme that the “[h]ate crime/ speech this has started is frightening”:

Further evidence of hatred directed at Travellers in response to the programme can be seen in the comments to a review of the programme in The Daily Telegraph.[70]

Nobby Nolan referred to Travellers as a “feral group”, adding “if we were rid of them our country would be a better place”.

David James referred to Travellers as “these vile people”.

T Coveney wrote of Travellers: “They just take, steal and destroy and contribute nothing to society.”

The racial group most targeted by hate speech in 2014 were GRT people.[71]

In response to a tweet from The Traveller Movement, 16 April, about the programme another person recommended “forced sterilisation” to “control traveller [sic] crime”:

Shortly after the programme first aired, another person called for a “sterilisation plan”.

To be clear: ‘forced’, that is involuntary, sterilisation is a crime. It is also a violation of a number of human rights (Articles 3 and 8, European Convention of Human Rights – incorporated into UK law by the Human Rights Act 1998) and at odds with what are now well-established principles of common law including the right to bodily self-determination. The recommendation of forced sterilisation after the programme carries disturbing echoes of forced sterilisation of Roma by the Nazis.[72]

The elimination of Travellers was also advocated by another person shortly after the programme started; this time “to get wiped out by coronavirus”.

Another person posting comments on an article about the programme stated that he would like to see Travellers “eradicated”, adding “nothing a random shotgun couldn’t sort. I will congratulate the one to start the trend, can’t stand them gypos”. The post received a reply advocating incineration of their caravans.

It is clear from the foregoing illustrative postings on social media and in other comments online that the programme was likely to encourage or incite the commission of hate crime or lead to disorder.

In view of the history of abuse and bullying targeted at Travellers, and in view of the stereotyping of Travellers – as explained in the early part of this complaint – it was entirely likely that the programme would do so.

Tom Copley, Deputy Mayor of London for Housing, wrote on 17 April that the programme “stigmatises a community that already suffers from discrimination [and] will only serve to stir up prejudice and hatred against the Gypsy & Traveller community”.

Concern about the stigmatising effect of the programme on Travellers was noted also by Nadia Whittome MP, below:

Ofcom’s Guidance to Section 3, adds, in part that in assessing ‘likely’ effect:

Material may contain a direct call to action – for example, an unambiguous, imperative statement calling viewers to take some form of potentially criminal or violent action. Material may contain an indirect call to action if it includes statements that cumulatively amount to an implicit call to act. For example, material which promotes or encourages criminal acts, or material which gives a clear message that an individual should consider it their duty to commit a criminal act.

There is in ‘The Truth About Traveller Crime’ no direct call to action to commit crime or engage in disorder. The Guidance refers to ‘an indirect call to action’ as one which may include an implicit call to act”. This Guidance is indicative. It does not purport to delimit the legislative duty on Ofcom set out in Section 319(2)(b) of the Communications Act 2013, viz: “that material likely to encourage or to incite the commission of crime or to lead to disorder is not included in television and radio services.”

The test of Ofcom’s duty is whether the content was “likely” to “encourage or to incite the commission of crime or to lead to disorder”.

It is suggested that the programme used a variety of techniques to stereotype Travellers which were or should have been known to be likely to lead to commission of crime or lead to disorder against Travellers.

The Code explains under the heading the ‘Meaning of “context” under Rule 3.1:

Key contextual factors may include, but are not limited to:

• the genre and editorial content of the programme, programmes or series and the likely audience expectations. For example, there are certain genres such as drama, comedy or satire where there is likely to be editorial justification for including challenging or extreme views in keeping with audience expectations, provided there is sufficient context. The greater the risk for the material to cause harm or offence, the greater the need for more contextual justification;

• the extent to which sufficient challenge is provided;

Ofcom has previously decided that “sufficient Challenge” comprises “sufficient and effective challenge”, Panthak Masle, KTV, 30 March 2019, 15:00 (p. 24).