26-minute read

Dermot Feenan

LLB MA LLM Barrister-at-Law FRSA

.

The vote in the United Kingdom in 2016 to leave the European Union has been associated with an increase in racially and religiously aggravated hate. Much of that hostility was initially directed at Poles and Muslims but it has extended through an increasingly confident display of prejudices, especially on the far right. It is now necessary to examine whether Brexit will rekindle one of the oldest forms of prejudice in England – against the Irish.

This focus on Ireland arises partly because of my own experience of racism as a northern Irish person in southern England in the run up to and following the Brexit referendum, and because that experience provoked an attempt to better understand the history of anti-Irish racism in Britain and how this connects to hostility and violence against others.

In this article, I gather together data on anti-Irish racism since the referendum within the context of an increase in Brexit-related racism generally. I contextualise this data within the longer history of anti-Irishness in Britain. I then consider how Brexit informs this racial othering. I conclude by considering the prospect of further anti-Irish racism if and when the United Kingdom (UK) leaves the European Union (EU).

Increase in Brexit-related racism generally

The UN Special Rapporteur on Racism reported in May 2018 that Brexit had contributed to an increased environment of racial discrimination and intolerance in the UK. Opinium reported that 71 per cent of people from ethnic minorities had by February 2019 faced racial discrimination compared with 58 per cent in January 2016, before the referendum.

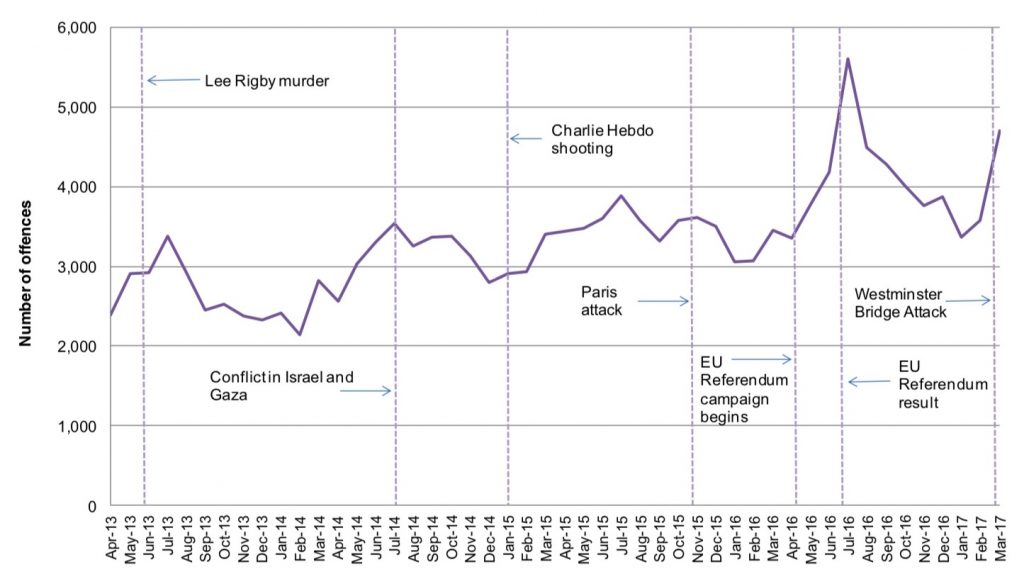

Home Office statistics for 2016/17 in England and Wales showed an increase of 29 per cent in hate crimes recorded from 2015/16, the largest percentage increase seen since recording began in 2011/12. This increase included a spike in racially or religiously aggravated offences from around the beginning of the EU referendum campaign on 15 April 2016 to just after the announcement of the result on 24 June, a day after the vote (see below).

While the Home Office does not itself collect data on hate incidents and hate crime with reference to specific racial/national/ethnic identity, the Crime Survey of England and Wales disaggregates data on racially motivated hate crime with reference to five categories: White; Mixed/multiple ethnic groups; Asian/Asian British; Black/African/Caribbean/Black British; Other ethnic group. In the period 2015/2016 to 2017/2018, adults in non-White ethnic groups were more likely to be victims of a racially motivated hate crime than White adults. These statistics do not, therefore, enable a determination of how many people are subject to race hate due to being Irish (or Polish, Romanian etc.). There is some evidence elsewhere, however, of anti-Irish racism since the vote.

Evidence of Brexit-related anti-Irish racism

The centuries-long history of such racism combined with contemporary anti-immigrant discourse means that further instances may occur as the UK moves towards and, if Brexit occurs, beyond exit from the EU. At the time of writing, the UK is scheduled to leave the EU on 31 October 2019.

There have already been some concerns about a reversion to anti-Irish racism. There is limited official data on the scale and incidence of anti-Irish racism in England. This is due in part to variation in how racism is defined and the absence of representative surveys. In this research, I examine accounts of anti-Irish racism among respondents to a survey. I also surveyed Twitter and five news periodicals online (Irish Independent, Irish News, Irish Post, The Irish Times, Irish World) for reports of anti-Irish racism in the period June 2016 through August 2019.

Shortly after the referendum, in late-June 2016, The Irish Post newspaper interviewed a number of people regarding anti-Irish views. One, Esther Doyle, 61, from London, was part of the generation that grew up with the notorious ‘No Irish’ signs in England. She experienced casual racism in her early life, which receded after the Belfast/ ‘Good Friday’ Agreement in 1998 – the major peace agreement between the British and Irish governments, and most Northern Irish political parties, that established new governance arrangements for Northern Ireland after decades of violent political conflict between the main combatants had formally ended. Since the result of the EU referendum, she feels she has once again experienced racism.

In March 2019, The Irish Times profiled a number of Irish people about their experiences since the referendum. Michael Connolly, number eight of thirteen children, of Irish descent in Maltby, a small mining community on the outskirts of Rotherham, reports a similar post-Brexit change. Born in 1962, he said:

“This bigotry gradually disappeared with the Good Friday Agreement, and so did heavy industry. Brexit has appeared like a shock to the system. I now hear the words my dad would have heard – ‘Go back to f**king Ireland’ – by people I grew up with, who know I was born here, who should know better” (asterisks in original).

Professor Michael Dougan, Professor of European Union Law at the University of Liverpool, also from the north of Ireland, was subjected to the following online anti-Irish abuse following a talk on the EU that he gave at the University of Liverpool: “fuck off back to paddyland you IRA cunt.”

The warning to leave England, was also experienced by Pádraig Belton, journalist and contributor mainly to the BBC, who recalled how the day after the result of the referendum when he publicly questioned the wisdom of the result he was told that because he was Irish he had no right to comment and “should bugger off home”.

Others profiled by The Irish Times reported anti-Irishness. Alan Flanagan, based in London, said: “the Brexit vote brought out an attitude that I had assumed long gone: anti-Irishness. I found myself standing in a bar while an old woman told me off for being Irish. Friends of mine had a similar experience on the bus.”

In April 2017, Richard Burgon, the Shadow Justice Secretary and Member of Parliament for Leeds East, received anti-Irish abuse by email after he was pictured with a Celtic shirt and Irish flags. Burgon, who was born in England and whose great grandparents moved from Ireland to Leeds, was called “Irish scum”. One email read: “Why do you live in England if you hate England? You ugly, retarded Irish piece of s**t. I see you would rather fly the evil Irish flag than the English or British flags. You have no future in England you anti-English scum. I hope you die from cancer you ugly Irish piece of s**t.”

One of the respondents to my survey, ‘Damian’ (whose name I have changed to protect his identity), shared a similar story to Alan Flanagan. Originally from the north of Ireland, Damian recalled an incident in a London pub in 2017. He had moved to the city to work as a TEFL (Teaching English as Foreign Language) teacher over 5 years before. He told me that during an organised class visit to a pub, an English woman who was about to leave the pub and learned of his identity made “several barbed comments” casting aspersions on his ability as an Irish person to teach English. She also insinuated that by arranging a visit to the pub he must be an alcoholic.

Flora Faith-Kelly, who was profiled by The Irish Times, said: “Since moving to London this year to complete my master’s degree, I feel this imposition of British opinion on how the Irish or Northern Irish should present, behave, think and speak grows stronger, highlighting the dangerous side of domineering British pride, perhaps the remnants from a conquering colonial history.”

Another of The Irish Times’ respondents, Geraldine Fahy, Kent, reported: “The overt racism encountered on a daily basis since Brexit is overwhelming. It almost feels like I have to apologise for not being British every time I walk outside the door.”

Similar experiences of anti-Irish racism were reported in August 2019 by The Irish Times in a further survey of its readers.

These accounts, from men and women, young and old, newly arrived and long-settled, reveal a common theme: anti-Irishness, which, for some, appears to be clearly related to the referendum vote. Some of this anti-Irishness takes the form of predictable racist stereotypes – the Irish person who isn’t bright enough to teach English – and xenophobic abuse – go back to Ireland.

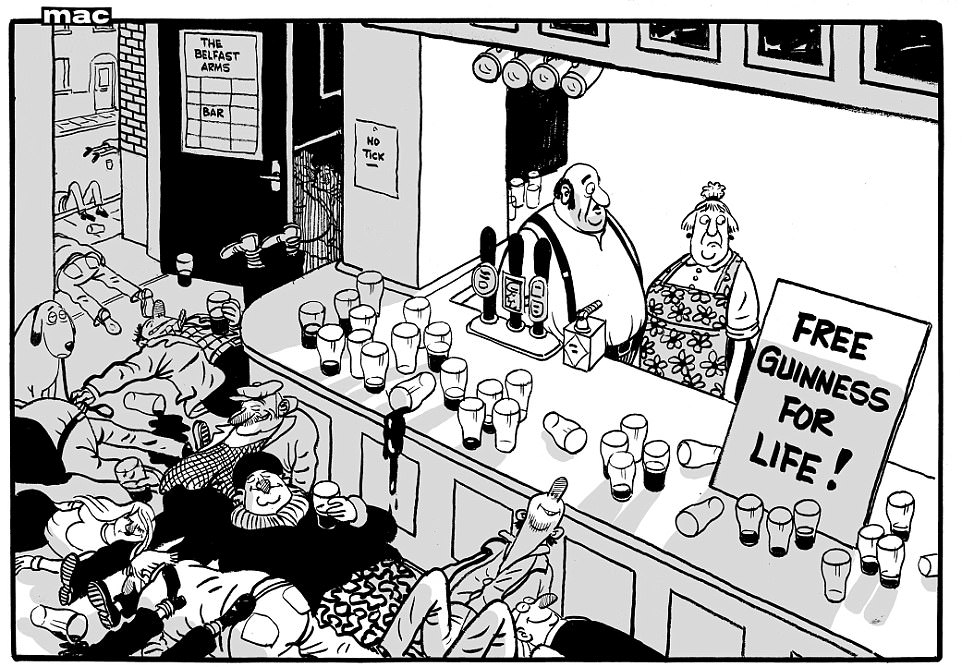

Further evidence of such anti-Irishness is apparent in the London-based, right-of-centre media. On 27 June 2017, a cartoon in the Daily Mail the day after the Prime Minister agreed to pay £1 billion to the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) to shore up the Conservative Party’s fragile majority in Parliament depicted the inside of a Belfast bar, with its patrons lying drunk on the floor beneath a sign on the counter: “Free Guinness for Life”. The cartoon was captioned: “Theresa May took some persuading but eventually the DUP clinched the deal” (below).

The cartoon tapped into the well-established racist stereotype of the Irish as drunks. The Mac cartoon depicts the drunken members of the DUP – a unionist party in Northern Ireland that has its origins in the Free Presbyterian Church, which abjures intoxication, and whose members would, in any event, likely eschew Guinness as “Irish”.

These instances of verbal and written racial abuse – much of it now communicated on social media – will be familiar to many, especially those who have studied the long history of anti-Irishness in England. To fully understand this recent anti-Irishness it is necessary to recall at least some of the key features of this history.

Long history of anti-Irish racism

Anti-Irish racism is probably one of the oldest continuous forms of racial othering in England. Professor Mary Hickman, former director of the Irish Studies Centre at the University of North London, showed in her 1995 book Religion, Class and Identity how over the previous 800 years racist tropes have existed and been modified by England to justify particular policies, including colonisation.

In the twelfth century the Irish were described in official accounts that legitimised the invasion of Ireland as “barbarous” people, characterised by “laziness” and “filthy practices”. After the Reformation, a principal marker for the Irish was their Catholicism. Anti-Irish views combined with anti-Catholic views in Protestant Britain such that in certain contexts anti-Popish belief and conduct became a racial signifier. Antipathy towards Catholicism remained a feature of anti-Irish views through the nineteenth century but they were based less on fear than a view that Catholicism was, in the words of E. R. Norman, “inimical to the proper conduct of civil affairs and national prosperity alike.” Anti-Catholic/ Anti-Irish hatred continues in Britain mainly among historically entrenched Loyalist communities (especially around street marches in Scotland).

By the Elizabethan era, as England consolidated its colonization of Ireland, the notion of the Irish as “stupid” became common. “Most of this was designed to show how English rule could be used to benefit the Irish,” said Dr Hickman (as she then was).

An associated trope was the idea of the Irish as ‘backward’, an ascription of cultural inferiority that served the logic of civilising the native – which would have profound effects worldwide. This was achieved in part by treating the bulk of the Irish population as ‘wild’. English forms of social class were retained for others. An English map of Ireland in 1611/1612 shows three types of people in Ireland: the ‘Gentleman’ and ‘Gentlewoman’; the ‘Civill’ Irish man and woman, and; the ‘Wilde’ Irish man and woman (see below).

As historian Jane Ohlmeyer observed in Political Thought in Seventeenth-Century Ireland: Kingdom or Colony, this “portrayal of the native Irish as ‘wild’ barbarians […] reinforced ethnocentric attitudes, confirming the racial superiority of the English over the Irish.” Keith Thomas, honorary fellow of All Souls, Oxford, notes in his book In Pursuit of Civility: Manners and Civilization in Early Modern England how a belief among the English in their superior civility shaped their relations with the Irish and, in turn, legitimized expansion of Empire, slavery, and international trade. Between 1690 and 1760, a key period in Britain’s imperialism, some 500 manuals on manners were published. The heart of this Empire was England, the symbolic legacy of which animates, in significant part, many who today support Brexit – even if it can be acknowledged that anti-Irish racisms may also have distinctive features in the different nations of the UK.

The persistence of the image of the barbarous Irish can be seen through to the beginning of the nineteenth century. John Pinkerton, Scottish antiquarian and historian, wrote in his history of Scotland that the Irish Celts were “savages”. The vestiges of this belief in England’s ability to civilise others was seen also during the period of violent political conflict in the north of Ireland between 1969 and the cessation of military operations in 1994. In 1972, Roger Evans, former Chair of the Cambridge Union and later Conservative MP, claimed in an interview in the USA that too many Irish in America was a problem. When asked by the host why, he replied: “they don’t seem to behave like the English somehow.” A Sunday Times editorial of 13 March 1977 opined: “The notorious problem is how a civilised country can overpower uncivilised people without becoming less civilised in the process.” The editorial implied that Britain was the “civilised country”; the Irish “uncivilised people”.

In the Victorian era the idea of filth, disorder and contagion was re-deployed to enable coercive intervention, purportedly in the interests of public welfare. Thomas Carlyle wrote in 1839 that “in his squalor and unreason, in his falsity and drunk violence” the Irishman was “the ready-made nucleus of degradation and disorder”, revealing a trope of the drunken Irish that would be amplified in the moralistic temperance movement in the late-nineteenth century, and which recurs in the Mac cartoon about the DUP in 2017.

Victorian-era illustrators depicted a prehistoric “ape-like image” of Irish faces to bolster claims that the Irish were an “inferior race” compared to Anglo-Saxons. This de-humanising representation is reflected in the account of the Irish poor by Englishman Charles Kingsley in a letter sent from Sligo in 1860: “I am haunted by the human chimpanzees I saw along that hundred miles of horrible country … [T]o see white chimpanzees is dreadful; if they were black one would not feel it so much, but their skins, except where tanned by exposure, are as white as ours”.

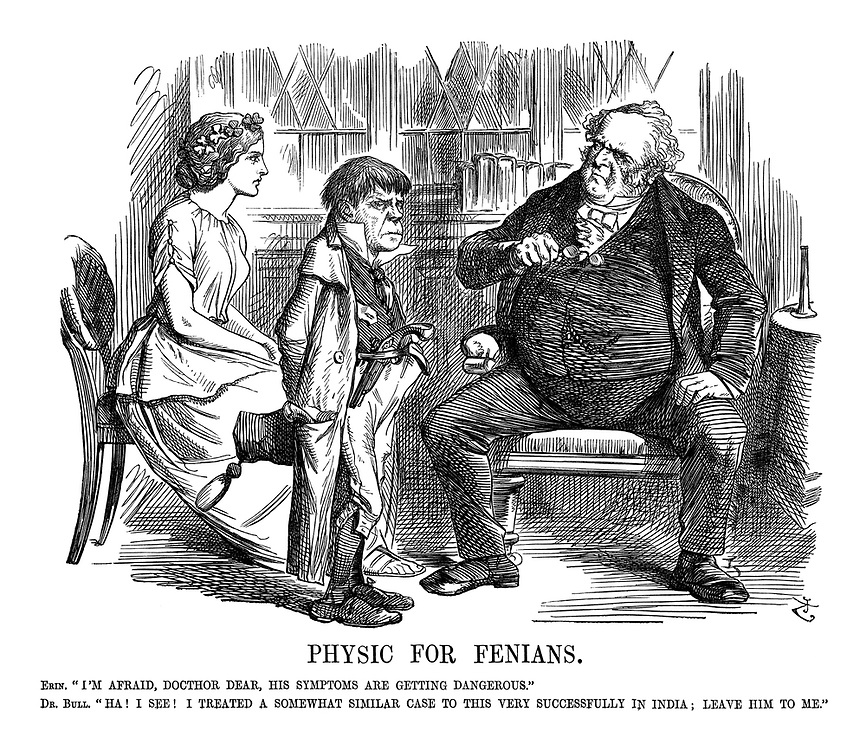

L. Perry Curtis, Professor of History at Brown University, showed in his book Apes and Angels: The Irishman in Victorian Caricature how anglophone political cartoons and caricatures in the 1860s changed the Irish man into a “dangerous ape-man or simianized agitator” (p. vii).

The consolidation of the British Empire and the ongoing need to subjugate Ireland led to proliferation of racist tropes, including that of the depiction of Irish people, as Professor Richard Haslam, St. Joseph’s University in the US, shows, as childlike or childish, troublesome, and in need of correction. Sometimes, this infantilization and the trope of simianisation coalesced, as in the cartoon by Tenniel for Punch in 1866 (below).

8 December 1866

A similar infantilization was used to subjugate another part of the British empire. Sir Alfred Milner, colonial administrator in South Africa, referred in 1901 to Africans as “children, needing and appreciating a just paternal government.”

The old anti-Irish racist tropes are evident in calls by a “Tory grandee” and former minister that the “Irish really should know their place” through to the op ed in The Daily Telegraph referring to ‘little Ireland’ and the Taoiseach and Tánaiste “trying to destroy, like wilful children, relations with an ancient and friendly neighbour” (emphasis added) (see excerpt below).

This infantilising trope of Ireland as problematically childlike (or childish) is evident also in the tweet by Gerard Batten, who was to become the leader of UKIP. He refers to Ireland as like the “weakest kid in the playground sucking up to the EU bullies” (see below).

Another channel for racist views, The Sun newspaper, wrote around the same time that it had “some advice for Ireland’s naive young prime minister: shut your gob and grow up” (emphasis added).

A further trope in the long history of anti-Irish racism was that of the lying or untrustworthy Irish person. In 1873, Edward Hamilton told his family that he was going to Ireland. His uncle wrote back to warn him about bringing home an Irish wife: “The whole nation lies and that is not a good quality in a wife.” The trope re-emerges over a hundred years later in English ex-Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s comment in 1999: “You can’t trust the Irish, they are all liars“.

Racial stereotyping continued throughout the last century, modified according to prevailing conditions. During the 1950s and 1960s “No Irish” signs on lodgings were reported. Military operations by the Provisional IRA (Irish Republican Army) during the subsequent period of political violence, especially when conducted in England between 1973 and 1992 led to a surge in anti-Irish racism, renewing tropes of drunken, lazy and dirty Irish – which have continued into the present century. In 2015, Jeremy Clarkson, former presenter on the BBC TV’s programme Top Gear, allegedly called his producer Irishman Oisin Tymon a “lazy, Irish cunt” during a confrontation. Like many other recent anti-Irish insults, this, too, has its antecedents in such earlier racism. In 1664, the English ornithologist Francis Willughby travelled to Spain and described its land and people: “almost desolate… tyrannical inquisition… multitude of whores… wretched laziness… very like the Welsh and Irish.”

The racist stereotype of Irish stupidity, first referred to in the Elizabethan era, has also persisted. It is evident in a number of reported cases taken under the non-discrimination provisions of race relations, and now equality, legislation. In McAuley v Auto Alloys Foundry Ltd. and Taylor [1994] IT/62824/93, for instance, the Industrial Tribunal found that the claimant had been discriminated against when subjected to insults and jokes such as “typical Irish”, “how could a Paddy do that?” and “typical thick Paddy”, and, after complaining, had been moved to a different job where the jokes and insults continued. He was ultimately dismissed. The Tribunal concluded that management at the company has not taken steps to stop such remarks being made, and there was “direct discrimination by using those racial words.”

A further type of racial stereotyping was identified by Mary Hickman and Bronwen Walter in their 1997 report Discrimination and the Irish community in Britain: a report of research undertaken for the Commission for Racial Equality; the idea of the Irish person as ‘fraudsters’. A report by Action Group for Irish Youth in 1993 found that this manifested especially for Irish people trying to access social security benefits; through unequal treatment in, and unnecessary, demands by staff for identification; denial of rights of access to benefits; unreasonable delays in payment; and unsatisfactory level of ‘customer service’, notwithstanding the requirement that Irish citizens not be treated as ‘aliens’.

There is some evidence of an increase in anti-Irish Traveller views. In May 2017, Nick Harrington, Conservative councillor, tweeted after Ireland failed to give the UK any points in the Eurovision 2016: “#Eurovision2017 thanks Ireland. You can keep your f’king gypsies! Hard border coming folks!” The tweet combines racism towards the Irish with racism towards Travellers, which latter group generally experiences some of the worst instances of racism in England as shown in the 2017 report by the Traveller Movement The Last Acceptable Form of Racism?

Brexit: a new order for racial othering

While a proportion of those voting for Brexit focused on the general constitutional issue of sovereignty, many were motivated specifically by how sovereignty would allow greater control of, and restrictions on, immigration. A significant part of the pro-Brexit political discourse and campaigning, especially in the UK Independence Party, involved anti-immigrant and xenophobic language. “Taking our country back”, a Brexit-theme, conveyed the sense of a “we” that was utilised by those with clear ethno-nationalist views.

Professor Anthony Heath and Dr. Lindsay Richards of the Centre for Social Investigation at the University of Oxford surveyed people during the Brexit negotiations who identified as British, English, Scottish, Welsh, Irish or European, and found that the English “seem to have a distinctive, rather ‘nativist’ or ‘ethnocentric’, character with bright boundaries against outsiders and an emphasis on ancestry as a criterion for national belonging.”

“People who subscribe to an exclusive English identity are also more willing to express racist views, while those with European identities tend to be the opposite,” they added.

A clear link between far-right racism, intimidation and violence and preference for Brexit was revealed days before the referendum. Labour MP Jo Cox was murdered by a man with links to right-wing political groups. He reportedly saw Cox as one of the “collaborators” who would betray “the white race”.

Increasingly, Islam has also been perceived as a threat that must be met with violence, as evident in a murderous van attack on Muslim worshippers in London in June 2017. Tell Mama, a government-supported organisation monitoring complaints of hatred against

Muslims, reported a 26 per cent increase in such incidents in 2017, with most attacks occurring on the street and targeting women. In this context, the dehumanising and vilifying reference by Boris Johnson, now Prime Minister, in August 2018 towards Muslim women wearing the burka as “letterboxes” resonated with a far-right view which it is believed he played to in order to enhance his political ambitions in the Conservative Party. Far-right groups such as Generation Identity publicly endorsed Johnson’s views.

The steep increase in recorded hate crime in England and Wales mentioned at the outset of this article (29 per cent in 2016/17), continued in 2017/18 (with a 18 per cent increase on the previous year).

The majority vote to leave the EU also legitimised racist and xenophobic public conduct that would otherwise have remained private.

In their research on EU migrants’ experience of hostility, anxiety, and (non)-belonging during Brexit, Taulant Guma and Rhys Dafydd Jones at Aberystwyth University quoted ‘Sonia’, a Portuguese national in Wales whose café was targeted in the aftermath of the vote: “Now because of Brexit everyone can say whatever they want because they think it is fine. Yeah, and I’ve had broken chairs, broken tables. Someone came here with a lead in his hand to threaten me.”

That anti-Irish racism, too, might reappear was already signalled briefly in 2012. The far-right English Defence League splinter group the North West Infidels organised an ‘anti-IRA’ march in Liverpool to the Annual James Larkin Society march and rally ‘Working Class Unity Against Racism & Fascism’. Their advertisement stated: “Over the past several years the City of Liverpool and North West England as [sic] seen the rise of anti British [sic] feeling projected on them by immigrant families from the Republic of Ireland. These people are much like the Islamics [sic], they take, take, take with one hand and abuse their host nation with the other” (see below).

The poster treats all families from the Republic of Ireland as members or supporters of the IRA, renewing old fears of IRA activity in England while exploiting contemporary anxieties about terrorism.

The campaign to leave the EU has also coincided with an increase in reporting of disablist, homophobic and transphobic hate crime. Police statistics show that LGBT hate crime more than doubled in England and Wales between 2013/14 and 2017/18. Taz Edwards-White, a manager at Metro, an equalities and diversity organisation in England, said: “There is a tension, and even within our own LGBT community there is a tension. I believe it’s a direct result of people feeling unsafe due to rise of the rightwing political movement.”

The Leonard Cheshire organisation reported a 33 per cent increase in online hate crime against disabled people between 2016-17 and 2017-18. Some of the othering associated with the campaign to leave the EU targets not only minorities on the basis of race/ ethnicity/ nationality but also other historically marginalised groups. This can, and does in some instances, lead to multiple detriment; such as for the Black Irish.

Part of this othering reflects a darker strain of right-wing ideology, readily discernible in the ablist, homophobic and racist worldwide of Nazism, but it draws from neoliberalism, fuelled by recent Tory policies, that communicates harmful stereotypes of disabled people as not ‘hard workers’ or deserving of state support or which dismiss gay people necessarily as Left-wing, identity-obsessed splittists. Ironically, many of the protections secured in recent years for people on the basis of their protected characteristics, such as sexual orientation, issue from the EU.

The extent of racism and xenophobia has increasingly been embraced within mainstream political parties, with Tommy Robinson appointed in November 2018 as advisor to UKIP and Conservative Party MPs such as Mark Francois, a member of the pro-Brexit European Research Group, referring on national television to “Teutonic arrogance” and “German bullying” in response to statements from the German-born CEO of international aviation manufacturer Airbus that the company may need to withdraw from the UK in the event of a no-deal Brexit.

After I moved from the north of Ireland to southern England in 2013 to conduct research in a university, it was clear that increasing calls for Brexit and associated anti-immigrant and racist views were moving from the fringes into the mainstream. In 2015, I encountered a clear instance of racist conduct by a white, English academic manager, who was also a serial bully, towards a Greek colleague in my workplace. Having spent most of my professional life committed to non-discrimination, I lodged a complaint. In my own case, the manager responded to one allegation of racism (“an Irish tendency to anger”) by asserting her own Irish “ancestry”, admitting “an Irish temper”, and stating that this statement referred to herself – sleights of hand that simultaneously avoided both her Englishness and the obvious racist stereotyping.

I was subject to serious and prolonged victimisation by the manager, her managers, co-workers, and, ultimately, the employer. My post was subsequently made redundant by the employer. Having also experienced the familiar racial stereotyping about the Irish and drinking, I subsequently took legal proceedings against the employer, which I brought to a satisfactory conclusion. It was notable, though not surprising, that a number of former colleagues who were not only required to respect equality but who espoused interest in non-discrimination, human rights and respect for dignity of the person were not only unwilling to confront the racism but ultimately allied themselves with the racist, bullying manager. These phenomena will, of course, be familiar to anyone with even a superficial knowledge of how racism (and bullying) operates in the workplace, but it underlined the parlous condition of minority ethnic staff in such organisations.

It also underlined the development of less overt forms of racism, which some sociologists call “modern” forms of racism. This form of racism involves subtle prejudicial behaviour. It has roots in existing racism but in the face of long-standing anti-racism laws and policies includes perpetrators engaging in harder-to-detect conduct, such as aversive racism. Subtler vestiges of anti-Irish racism are often apparent in calculated indifference to the legitimate expectations or rights of the Irish.

This is evident in the lack of concern in some quarters over the effects on the Irish of a ‘hard-Brexit’ for the hard-won peace after the recent period of violent political conflict centred on the north of Ireland. Jacob Rees-Mogg Conservative MP for North East Somerset in England and member of the extreme-right European Research Group, referred from the backbenches approvingly in a debate in the House of Commons on Brexit and the issue of the Irish border to “our ability, as we had during the Troubles, to have people inspected.” This statement is indicative of a long tradition of colonial, wealth-inured hauteur towards Ireland’s concerns. The centuries-long relation between colonisation and racism means that the Irish are subject to a distinctive type of colonial-racial subordination that would not be experienced by those groups which have not been subject to British imperialism at all or to the same extent, for instance the Russian people – whose motherland has never been colonised by Britain.

Similarly, Boris Johnson, then Foreign Secretary, said of the significance of the Irish border to Brexit negotiations at a meeting in June 2018: “It’s so small and there are so few firms that actually use that border regularly, it’s just beyond belief that we’re allowing the tail to wag the dog in this way. We’re allowing the whole of our agenda to be dictated by this folly.” Embedded within this formulation is the idea that Irish concerns about the border are subordinate to perceived UK interests. The addition of the words “our agenda to be dictated by this folly” hints darkly at both an external dictatorial threat and insinuates that parity of concern for the Irish question is foolish.

There exists within this view an element of racism, which is that the Irish and Irish issues are not to be taken seriously. It is, again, a throwback to a colonial mentality. Seán Ó hUiginn, former Irish diplomat, said in August 2019, with reference to Britain’s approach to Ireland in relation to Brexit:

“Burke said that the English have only one ambition in relation to Ireland, which is to hear no more about it. And that is still not a bad working maxim if you want to analyse British relations. When they have to focus on it, there is another mechanism which comes into play which I would call the Irish anomaly. Something that would be taken very seriously in another context can be disregarded if it comes with an Irish label. The Border is a classic example of this. Why didn’t the British focus on the fact that they had an extensive land border with the European Union? The answer is that it was in Ireland. It wasn’t serious.”

Ó hUiginn’s comment contains within it a significant distinction which is relevant not simply to anti-Irish racism but additional forms of racial othering. At one level, inter-governmental relations are properly conceived as involving the ‘British’ but the campaign for Brexit has reinvigorated an older truth; that a certain idea of Britishness is in fact no more than a narrow, ahistorical concept of English identity. It is a point well made by Professor Krishan Kumar in his book The Making of English National Identity.

In the event of the UK leaving the EU

Is there a risk of renewed anti-Irish racism in the event that the UK leaves the EU?

It is likely that the Irish will experience an increase in racism. Considerable data already shows an increase in racism since the Brexit referendum in 2016. Some of this racism is directed at the Irish.

Ireland, and, in the minds of some, by association, the Irish, are partly to blame for the delay in the UK withdrawing from the EU, which was initially scheduled for 29 March 2019. Some focus on that part of Withdrawal Agreement called the ‘Irish backstop’, which is designed to ensure that Northern Ireland’s unique relationship with Ireland is not damaged by the UK’s withdrawal from the EU without a deal. Given the distinctive political and security significance of the border between Northern Ireland and Ireland, the backstop seeks to ensure that there is no ‘hard’ border on the island of Ireland. This is achieved through the Agreement by insisting that the UK remains within a customs union unless the UK and EU agree a final deal at the end of a transition period or if the final deal does not guarantee a ‘soft’ border. This part of the Agreement has already triggered anti-Irish insults. The election of Boris Johnson as Prime Minister raised the stakes given his insistence that the UK would leave on 1 November 2019, deal or no deal. Ireland and the EU have insisted the backstop must remain.

Social media and online commentary have increasingly carried, especially since the Withdrawal Agreement, more abusive anti-Irish insult and stereotyping, recalling the tropes of stupidity and violence mentioned above. In a series of posts online in response to the EU Parliament President’s statement in September 2019 that the UK had offered no initiative to re-open Brexit talks, one ‘Paul Nicholson’ stated: “Get your act together EU and tell the idiotic Irish to sort themselves out!”. He added: “The Irish cant [sic] even get on among themselves, have’nt for generations” (see below).

Comments on a news item in The Daily Telegraph online in August 2019 started with the statement that Boris Johnson said before the EU referendum that Brexit would not affect the Irish border. The subsequent posts are indicative of anti-Irishness (see below). ‘Neil Davies’ replied: “It will not; unless the Irish choose to let it” – this, in spite of the fact that the British government is one of the signatories to the Belfast Agreement. ‘Chuck Wingnut’ added: “Actually, most people in England (of which I’m one) don’t give a fek what happens to Ireland so long as it’s nothing good. A lot of us haven’t forgotten the Birmingham bombings.”

It is entirely plausible that in the event of Brexit the Irish will be on the receiving end of further such abuse, not least because of the (mis)perception that Ireland has frustrated Brexit.

Some trends in the increase in racism are also potentially significant. The Opinium survey in May 2019, reported an almost 53 per cent increase between January 2016 and February 2019 in racist comments made to sound like a joke. The nature and scale of this increase are notable.

Racist comments made to sound like a joke represent an insidious form of racism, couched as banter or jest; discernible to the target but carrying an element of deniability for the person who uses the racism. It can be difficult to call out such behaviour, and the perpetrator can engage in gaslighting, evading responsibility by framing the target as mistaken or paranoid. The ‘joke’ may serve two purposes: through such deniability, to unsettle the target and secondly to make the target a subject of ridicule, not worthy of respect. Psychologically, racist comments made to sound like jokes can also – though this is not necessarily so in all cases – be a precursor or accompaniment to other forms of racism, such as overt abuse or discriminatory withdrawal of opportunities. The literature on racism amply shows how ‘jokes’ have been used tactically to maintain racism.

Brexit will set in motion its own dynamics of identity that recall forces in previous Anglo-Irish relations. Michael de Nie shows in his 2004 book The Eternal Paddy: Irish Identity and the British Press, 1798-1882, how Britain’s chauvinistic notions of Irish class, racial and religious identity were instrumental in shaping policy towards the Irish during the profoundly important century which started with plans for the Act of Union 1800 through to the development of the Home Rule movement in the late-eighteenth century, but throughout was the “fundamental assumption that the root of the eternal Paddy’s difficulties was his Irishness” (p. 35).

Economic interests, such as concern about scarcity of secure employment or differential standards of living, may significantly affect how the Irish are perceived post-Brexit. The first racial othering of the Irish by Geraldus Cambrensis (Gerald of Wales) as part of the Anglo-Norman conquest of Ireland. He drew on political economic assumptions about the Irish in his Topographia Hibernica (The Topography of Ireland) around 1188: “this nation, holding agricultural labour in contempt, and little coveting the wealth of towns […] their greatest delight is to be exempt from toil, their richest possession the enjoyment of liberty. This people, then, is truly barbarous.” His vilification of the Irish served ultimately to dehumanise the native people as part of a policy of subjugation to English rule. Tactically, it sought to undermine the widespread view of Ireland as a centre of Christianity and civilisation. It was treated as fact for centuries, published in English for a new audience in Elizabethan England eager to justify further colonisation in Ireland.

The Irish who have recently benefitted from being seen as fellow members, with the UK, of the EU will, as one of the largest labour sources in Britain, begin to look and sound increasingly different if the UK leaves the EU. Catherine Hennessy, an Irish-born counsellor and psychotherapist who came to England in 1987, says: “As an Irish emigrant in England being a citizen of Europe was a kind of meta-identity that helped to transcend the traditionally oppositional nature of identity relationships between our two Islands.”

A boom in Ireland’s economy and a decline in the UK’s may re-calibrate that perception to one closer to the respect towards Ireland during the “Celtic Tiger” years, but centuries of beliefs about racial superiority is very unlikely to disappear. More likely, those Irish who prosper in England may be viewed with resentment. In a depressed British economy, migration of Irish under Common Travel Arrangements that are unaffected by Brexit may trigger distinct pushback from some in Britain.

The referendum vote in favour of Brexit mobilized ideas of “the people” (evident, for example, in the Daily Mail’s depiction of judges as “Enemies of the People” and calls for a “Peoples’ Vote”). As Professor Étienne Balibar argues in Race, Nation, Class, the modern state must mobilize itself through creation of “the people”. Given the nationalistic objective of some Brexit voters, it should be no surprise that if (and when) the UK leaves the EU new racial mobilizations will coalesce around ideas of the nation, re-defining the ‘people’ entitled to respect and rights and, conversely, those who are not.

A further shift in nationalistic belief and conduct in England could very well lead to an increase in anti-Irish racism. Racist and Islamophobic speech and conduct from US President Donald Trump led to a leap in racist violence and a resurgence in white supremacism across the states. While much of the violence has targeted African-Americans and those perceived to be Muslims, an Irish family-owned store in Kansas was targeted in June 2018 with the graffiti “immigrants not welcome”. One of the store’s owners, Kerry Browne, said the “political environment has changed” since Trump was elected President.

A consolidation of colonial, imperialist racist tropes in England, evident among some Brexiteers, also seems possible; and with it a rekindling of old prejudices against, amongst others, the Irish. Politicians on the right within the Conservative Party, such as former Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson, expressed views that combine a colonial nostalgia with jingoistic emotions associated with war. In Johnson’s case, these views are also enmeshed in the contemporary othering of Muslims, as can be seen in his reference to Muslim women wearing the burqa as “letter boxes”.

Professor Bronwen Walter, who has studied and written on the experience of the Irish in Britain for almost forty years, told me that “there would be a danger” after Brexit that anti-Irish racism “rears its head” again.

The forms of racism will likely be familiar, reflecting old techniques of othering, but they are attaching to new forms allowed by the decision to leave the EU. The administrative apparatus created to police Brexit allows those administrative staff who have absorbed the Brexit language of “taking back control of our borders” and its accompanying discourse of a ‘hostile environment’ for immigrants, to exercise their gatekeeping role – especially across a range of statutory services, including immigration, health services, and social security – with increased xenophobic fervour.

There is also a risk of a further slide to the far right. In August 2018, the Metropolitan Police’s former head of counter terrorism, Sir Mark Rowley, said that “for the first time since the Second World War, we have a domestic proscribed terrorist group. It’s right wing. It’s neo-Nazi. It’s proudly white supremacist.” His successor Neil Basu, Metropolitan Police assistant commissioner, said in January 2019: “My concern is the polarisation, and I fear the far-right politicking and rhetoric leads to a rise in hate crime and a rise in disorder.”

Given the history of anti-Irish racism in England, it would be wrong to assume that any rekindling will grow only from far-right organisations. Hickman and Walter found that the two most common sources of racial harassment for Irish people were their neighbours and the police, with statutory agencies occasionally named.

Conclusion

There are those who would treat the long history of hostility against the Irish as reflecting religious or class animosities and deny that the Irish had any racial identity apart from the British. But this account shows otherwise. As de Nie argues: “race was a metalanguage in Anglo-Saxonist discourse, a vehicle for expressing multiple anxieties and preconceptions, among them class concerns and sectarian prejudices” (p. 5).

The English view of Irish inferiority has lasted for centuries, much longer than the relatively short interlude since the Belfast Agreement of 1998 secured a form of peace between the countries and those fighting over the status of Northern Ireland. While many of the instances set out in this article reveal interpersonal insults, these are linked to deeper ideological beliefs which inform political arrangements.

Brexit draws out old racisms, imperial nostalgias of English superiority. The shifting economic and constitutional realities raised by Brexit, set against unprecedented migratory flows to Europe from conflicts in Syria and sub-Saharan Africa, and alongside increasingly fluid identities, means that new forms of racial othering emerge, with older forms rekindled afresh. The actual and potential effects of these new forms of othering are myriad, ranging from the personal and collective injuries of insult, through the unsettling of the Belfast Agreement, to major shifts in economies and international relations; each of which require attention and appropriate response.

___________________________________________________________________________

The names and certain key identifying details of people who contacted me confidentially have been anonymised to protect their identity.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Karen Bensusan, Ruairí Cullen (Policy and Public Affairs Officer, Irish in Britain), and Professor Bronwen Walter (Anglia Ruskin University) for comments on a draft of this article; Hester Swift (Foreign and International Law Librarian, Institute of Advanced Legal Studies, University of London) and staff at the British Library for library assistance; and Brian Dalton (CEO, Irish in Britain) for circulating details of the survey via the Twitter account of Irish in Britain. Go raibh maith agat. Any errors are my responsibility alone.

.

© Dermot Feenan 2019