20-minute read

Dermot Feenan

LLB MA LLM Barrister-at-Law FRSA

.

Comments by Toby Young, writer, about the involvement by Greta Thunberg, the 16-year-old Swedish climate change activist, in protests organised by the environmentalist organisation Extinction Rebellion in early April in London, reignited academics’ concerns about Young from 2018.

At the start of 2018, many academics moved swiftly to protest the announcement of the appointment of Toby Young to the Office for Students (Ofs), the new regulator for higher education in England and Wales. Almost immediately, reports surfaced of controversial comments that Young had made about women, people with disabilities, the working class, and gay men. The Conservative Party defended him. Opposition parties demanded his resignation. A petition calling for his resignation received 221,509 signatures.

I joined others in raising grave concerns about the appointment based largely on my experience as an academic of almost 15 years’ experience and as a former Independent Assessor for the Commissioner for Public Appointments for Northern Ireland. Those concerns focused on the Principles of Public Life, which require that “[h]olders of public office must act and take decisions impartially, fairly and on merit, using the best evidence and without discrimination or bias.” I noted also that the Commissioner for Public Appointments did not choose to inspect paperwork for the competition, and that Young’s views were hardly compatible with the statutory duty on the OfS regarding non-discrimination. Ultimately, the pressure led Young to resign his position on 8 January 2019.

This blog recalls the controversy about the appointment and resignation of Young, in part because it is vital in politics and activism to remember achievements, to renew consciousness, and to re-assess whether and how any similar actions can be deployed in future. It is too easy sometimes to forget such achievements as simply ‘done’, consigned to the past, and, ultimately, forgotten. By looking back at this achievement, I also assess the significance of the academic opposition to Young’s appointment by reviewing the ensuing fifteen months in which the tertiary education sector underwent a nationwide strike among academics, witnessed numerous controversies over vice chancellors’ pay and conduct, and faced widespread redundancies. The blog also seeks to elaborate the perceptive observation by punkacademic, made in the midst of the appointment controversy: “The Young appointment is awful, of course, but to question the appointment on its own is to fall into the same trap academics often do – not to question the underlying logic of the system but how it is implemented.” I address that “underlying logic” with reference to the duties of the Office for Students and its underpinning ideology in the Conservative Party’s approach to tertiary education.

Young’s views

Young had made numerous comments about women’s breasts, including to those of Padma Lakshmi, with whom he appeared on the US reality show Top Chef. He claimed in another tweet, now deleted, that a photoshoot with Lakshmi looked the way it did because he had his “dick up her arse”.

In an essay in 2015, Young proposed that poor people be offered the opportunity through genetic engineering to choose which embryos to have with reference to future intelligence: “once this technology [genetically engineered intelligence] becomes available, why not offer it free of charge to parents on low incomes with below-average IQs? Provided there is sufficient take-up, it could help to address the problem of flat-lining inter-generational social mobility.”

Young also came in for criticism for his comments on disability. In an article for The Spectator, he referred to the word “inclusive” as “one of those ghastly, politically correct words.” He continued: “Schools have got to be ‘inclusive’ these days. That means wheelchair ramps […]” Wheelchair ramps may be an essential ‘reasonable adjustment’ as required under equality and non-discrimination law.

In a book called The Oxford Myth (1988), Young – whose father Lord Young secured a position for his son at Oxford despite the boy not making the grade – described working-class grammar school boys who secured places at Oxford as “universally unattractive” and “small and vaguely deformed”. He recounted how the arrival of the ‘stains’, as working-class students were known, had changed the university. He wrote “it was as if all the meritocratic fantasies of every 1960s educationalists had come true.”

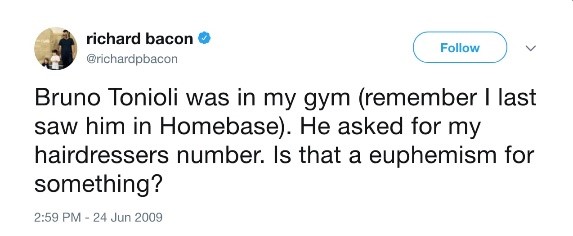

He also made comments demeaning of gay men. In responding to a tweet from someone on Twitter, he wrote that a request for the number of your hairdresser from a gay celebrity meant: “I want to bum you.”

These were among the most widely circulated comments made by Young, but there were numerous others; including joking to a female friend on Twitter that he had masturbated over images of starving children scavenging from a rubbish dump in Kenya.

Office for Students

Young had been appointed to the OfS as one of its eleven board members.

The OfS was established under the Higher Education and Research Act 2017, in part to replace the Higher Education Funding Council for England and the Office for Fair Access. The OfS has a range of duties, including regard to the need to encourage competition between English higher education providers. The OfS also has responsibility for managing the controversial Teaching Excellence and Student Outcomes Framework (TEF) and National Student Survey, and for monitoring ‘Prevent’.

Young was seen by ministers as a leading public supporter of the Government’s educational policies, and of the creation of the OfS in particular.

Amongst the Office’s other duties it “must have regard to the need to promote equality of opportunity in connection with access to and participation in higher education provided by English higher education providers”.

The OfS is a public authority, and as such, under the Equality Act 2010, it must in the exercise of its functions, have due regard to the need to—

- eliminate discrimination, harassment, victimisation and any other conduct that is prohibited by or under this Act;

- advance equality of opportunity between persons who share a relevant protected characteristic and persons who do not share it;

- foster good relations between persons who share a relevant protected characteristic and persons who do not share it.

In view of the evidence of Young’s offensive comments towards women, degrading comments about the working class and people with disabilities, eugenicist views, and disrespect towards gay men, it is entirely reasonable to question whether Young could have contributed properly to discharging these duties.

And, let’s recall too that Young was deemed appointable by a panel chaired by Sir Michael Barber, chair of the OfS.

It was only after Young resigned that Barber said: “many of his previous tweets and articles were offensive, and not in line with the values of the Office for Students.”

The Commissioner for Public Appointments

The Commissioner for Public Appointments (‘the Commissioner’) is a body set up by law to independently regulate appointments by Ministers to the boards of public bodies in accordance with the Government’s Principles of Public Appointments and Governance Code.

Appointments must be conducted according to the Governance Code.

The Commissioner conducted an investigation into the competition following concerns about Young’s appointment and the appointment of the ‘student experience representative’ to the Board of the OfS. The Commissioner found the department to be in breach of the Code in failing to consult on an appointment without competition.

The Commissioner also found that due diligence was “inadequate and not conducted in respect of all candidates on an equal basis, comprising the principle of fairness in the Governance Code.” He noted that “political factors completely unrelated to the remit of OFS were cited by [an official] in objecting to the preferred candidate”.

The Commissioner revealed that the former higher education minister asked officials to inform Young about the vacancy.

The Commissioner also noted that the evidence showed that “there had been a desire amongst ministers and special advisers not to appoint someone with close links to student unions [and that] this was not made clear in the advertised candidate information.” The appointment panel initially identified a student union leader as appointable for the student experience representation role on the Board. The report recorded that “papers indicate that political factors completely unrelated to the remit of the OFS were cited by the special adviser in objecting to the preferred candidate.” The Commissioner noted his concern “at the catch-all nature of the […] justification for rejecting the preferred appointable candidate” and concluded that this aspect of the competition “had serious shortcomings in terms of the fairness and transparency aspects of the Code.”

The Commissioner recommended in the wake of the controversy over Young’s appointment to (and subsequent resignation from) the OfS that panels should conduct ‘due diligence’. The Commissioner noted in his Annual Report for 2017/18 that departments had responded “positively and sensibly” to his suggestions on “improving due diligence inquiries about candidates, and this has now become routine practice in the main.”

Universities UK

During the media furore about Young’s appointment, Alastair Jarvis, the chief executive of Universities UK (UUK), emailed all VCs: “I do not believe it would be in the best interests of the sector for UUK to publicly challenge this ministerial appointment.”

UUK is a registered charity whose objects are to promote, encourage and develop the university sector of higher education in the United Kingdom. UUK states on its website that it is “the collective voice of 136 universities in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.”

Many academics have criticised UUK for, variously, its support for the proposal by USS to move from a defined benefits scheme to a defined contribution scheme which would have left members poorer. Criticism was raised about UUK’s claim to represent universities, not least when a number of vice-chancellors, including Professor Stuart Croft at the University of Warwick and Professor Robert Allison, Loughborough University, publicly communicated their concerns about the USS proposal.

UUK was also challenged on how it conducted its consultation regarding the USS proposals. Professor Dame Athene Donald, Master of Churchill College, University of Cambridge, raised concerns that the period of consultation did not permit time to consult properly. She referred also to “the obscure, and possibly misleading way” in which UUK had referred to responses from the University. Professor Felicity Callard also wrote that UUK had been “misleading”. Others called for transparency in UUK, with 13,108 signatories to a petition demanding that UUK be subject to freedom of information law.

UUK could, and should, have challenged Young’s appointment. Young was manifestly unfit to hold that public office. The process of appointment was later shown by the Commissioner for Public Appointments to have been flawed.

Contrary to Jarvis’ declaration, UUK has, on occasion, though this may be too charitable, ‘challenged’ government policies; as illustrated in UUK’s warning to the government on 4 January 2019 against “the UK crashing out of the EU without a deal.”

UUK also had adopted the following policy at the time of Young’s appointment: “[w]e support and promote life-changing opportunities for people of all ages and backgrounds at every university.” It went on: “We believe that a diverse and inclusive organisational culture – one in which everyone feels valued and can learn or work to their full potential – makes for a more effective and productive higher education workforce.” UUK referenced beneath these statements, its support for disabled students and tackling sexual misconduct.

When Alastair Jarvis sent the email to all vice chancellors about Young’s appointment, there was abundant evidence in the public domain that Young had engaged in sexist comments, denigration of the working class, disparagement of the needs of disabled people, and troubling endorsement of progressive eugenics.

While UUK remained unwilling to intervene, the National Education Union, representing nearly half a million teachers and lecturers, publicly condemned Young’s appointment.

Others took on the responsibility that UUK failed to meet. Robert Halfon, Tory MP, and chair of the education select committee, wrote that the appointment reinforced the image of the Conservative Party as “heartless and cruel”, referring to Young’s “darker comments on disability, embryos, eugenics and working-class children.”

The Conservative Party

Jo Johnson, the then-universities minister also defended Young’s appointment in the House of Commons. He said, “we want to encourage Mr Young to develop the best sides of his personality”. This condonation of misconduct by confusing public office with a finishing school is typical of a certain type Conservative elitism, allied with a mode of governing which Professor Aeron Davies calls “reckless opportunism” – where politicians create and game their own evaluation systems. Boris Johnson, then-foreign secretary, and Michael Gove, environment secretary, themselves censured for offensive comments, also defended Young’s appointment. Johnson called him the “ideal man for the job”. Gove agreed, tweeting: “Quite right too – how many of Toby Young’s critics have worked night and day to provide great state schools for children of every background?”. Equally dubious endorsements came from Priti Patel, who resigned her post as Secretary of State for International Development following allegations that she had breached the ministerial code. A slew of backbench Tory MPs, though not all, piled in to defend Young. Margot James MP said he was “worthy of his appointment.”

The party urged its backbench MPs to deflect criticism of Young’s appointment by attacking the Labour Party. Theresa May did not act in such a way that would have made Young’s position untenable. She said: “He’s now in public office, and as far as I’m concerned if he was to continue to use that sort of language and talk in that sort of way, he would no longer be in public office.” Even though this clearly indicates that Young’s language was incompatible with holding public office (and indeed implied that she could arrange to have him removed), the Prime Minister would not say so.

Opposition parties were, by contrast, unequivocal in their condemnation of the appointment.

Senior figures in the Labour Party, Angela Rayner, Shadow Secretary of State for Education, and Dawn Butler, Shadow Secretary of State for Women and Equalities, urged the Prime Minister to ditch Young.

Caroline Lucas, MP and former leader of the Green Party, led a cross-party coalition of 36 MPs in tabling an early day motion in Parliament calling for Young’s resignation. Not one Tory signed the petition.

Sir Vince Cable, Leader of the Liberal Democrats said in the wake of May’s statement that: “she should be firing him. This is a man who has a record of misogyny and backs eugenics. His appointment shows poor judgement.”

Even after Young’s resignation from the OfS and the damning report about the appointment from the Commissioner for Public Appointments, the Tories did not acknowledge any blame. The then-education minister stated in the House of Commons that there had been “question marks, quite rightly, over the appointment”. There were not simply “question marks”. There was clear evidence of departmental interference and political bias in the appointments process, and party-political defence of someone widely believed to be unfit for public office.

Gyimah went on to say that: “The same due diligence was carried out by the same advisers on all the candidates.” This directly contradicts the finding by the Commissioner for Public Appointments that “by its own admission did not delve back extensively into social media […] by Mr Young. However the social media activity of the initially preferred candidate for the student experience role was extensively examined” (para. 22). Such falsifying was one of the reasons which led me to welcome Gyimah’s resignation from the post of Minister of Universities, Science, Research and Innovation on 30 November 2018.

The Conservative Party’s defence of Young’s appointment was an attempt to shore up the ideological underpinnings of their neoliberalist approach to the tertiary sector. As well as an older form of political power: class-nepotism. The party’s defence of Young also represented party-political interests: Young, a Conservative, was their man. It is essential to recognise the way in which these factors combine in Britain, not least in a sector historically informed by class privilege and wealth – a state of affairs that has received insufficient attention in academia.

Lessons for activists

Select committees

The public intervention by Robert Halfon, the chair of the education select committee, in an article for The Sunday Times on 7 January 2018, was important. It was significant that Halfon has a disability. Young had made comments denigratory towards people with disabilities and had also embraced eugenicist theories. The chair of the OfS faced the possibility of being called before the committee to explain what would clearly be indefensible.

Select committees increasingly play a role in holding individuals and organisations to account, as illustrated when Amber Rudd, then Home Office minister, was interviewed by the Home Affairs Committee as part of its enquiry in 2018 into the Windrush scandal. Rudd denied the Home Office had targets for deportation of illegal immigrants. Leaked e-mails subsequently suggested there were targets, and that Rudd was aware of them. She later resigned from her post.

Select committees can influence policy making. UCL’s Constitution Unit found that a third of select committee recommendations for significant policy change were implemented by government. Academics should be alert to the opportunities for influencing policy through submission of written or oral evidence.

Regulation of public appointments

Appointments to most public bodies in the United Kingdom are regulated. Relevant appointment competitions must adhere to the Governance Code.

Candidates for appointment must adhere to the Nolan Principles in Public Life.

The Commissioner for Public Appointments has power to conduct an investigation into any aspect of public appointments “with the object of improving their quality” and may conduct an inquiry into the procedures and practices followed by an appointing authority in relation to any such appointment whether in response to a complaint or otherwise.

The investigation into the competition to which Young applied was opened, according to the Commissioner, because of the “considerable public controversy” surrounding the appointments process. It would be open to anyone to make a complaint.

Academics can also apply for appointment to public bodies if they meet the eligibility criteria. Many prominent public bodies have academic members, including the Office for Students. Vacancies for public bodies are advertised through a Cabinet Office webpage.

Power of online social media

Young’s appointment provoked many academics to take to social media, especially Twitter, to engage with an aspect of tertiary education which might not otherwise have received attention. The controversy over the appointment was for me, someone relatively new to Twitter, an opportunity to witness and contribute to solidarities which would become increasingly evident throughout the USS strike and in follow-on academic activism. For someone of my generation, who entered academia before the arrival of the internet, it has expanded opportunities for discourse well beyond what had often been limited to the staff common room and conference venues.

Being part of that wave of protest that lead to the resignation of Young is heartening. As noted by many other academics in the wake of the UCU strike of 2018, social media provided new opportunities for connecting with like-minded people. It broke down the sense of isolation that can sometimes come from academic work, and which is aggravated within neoliberalism’s valorisation of the individual and solo achievements (with correlative judgement about personal failure), and atomising performance management.

It is clear that many academics now see themselves as active participants in the politics of the tertiary sector. Historically, the old complacencies seem to have been shaken off. While universities have not, certainly since the Second World War, been free from significant state intervention, as Professor Stefan Collini notes in What Are Universities For?, academics are increasingly recognising the ideological issues at stake: between education as a public good or as a marketable commodity. The much-criticised divide between ‘us and them’ can, however, be a real, important battle-line in ideological conflict.

It is difficult to conceive that those who became politicised during the Young appointment debacle and subsequently will lose this consciousness and their activist energies in the foreseeable future.

The Tories

The OfS fiasco demonstrated that the Conservative Party and senior ministers, as well as the Prime Minister, came to the defence of their ‘man’ and failed to act in the public interest. This conduct is not an isolated incident. One of the greatest threats to the tertiary sector since the Conservative’s achieved power in 1979 and subsequently has been the erosion of large swathes of academic autonomy, degrading of professional expertise, attacks on academic freedom of expression, and the implementation of a market-based approach to research and teaching. Many of the resulting problems with excessive workloads, casualisation, precarity, bullying and harassment are linked to this deeper ideological change. The controversy over Young’s appointment and this broader context suggests that it is entirely reasonable to adopt a view that tertiary education, at least, will be better off without the Conservatives in power.

The operations of neoliberalism exposed

Young’s appointment also cast light on what had previously been for some the shadowy new body called the Office for Students. The appointment brought into sharp relief certain ideological interests and approaches to tertiary education which revealed, even if not immediately articulated as such by many, the operations of neoliberalism. The shift to neoliberalism is not new. Since the 1960s, conservatives, especially those on the neoliberal right, have sought, as Professor Henry Giroux observed in relation to education: “aggressively to restructure its modes of governance, undercut the power of faculty, privilege knowledge that was instrumental to the market, define students mainly as clients and consumers, and reduce the function of higher education largely to training students for the global workforce.”

The Office for Students is but one component of this neoliberal shift, with its duty to encourage competition between English higher education providers. Competition among universities has allowed huge levels of indebtedness as providers try to attract student fee income with increasingly glamorous buildings, but it has also led providers to game the measures purporting to evaluate quality, and to cut staff costs which has led in turn to a cascade of redundancies and damagingly high levels of casualisation. The OfS is symptomatic of changes well-documented by those writing about universities in the United Kingdom especially over the last seven years, including Stefan Collini (What are Universities For? 2012); Roger Brown and Helen Carasso (Everything for Sale? 2013), and Andrew McGettigan (The Great University Gamble: Money, Markets and the Future of Higher Education, 2013).

But any reflexive academic will have been aware of the other symptoms associated with Giroux’s analysis, including: deliberate denigration of academic authority (as evidenced in comments by Michael Gove in June 2016 about having ‘enough of experts’); erosion of academic autonomy at the expense of new managerialist authority; increasing metricization of work (though REF, TEF and KEF); the growth in the valuing of methodologically discredited surveys (such as the National Student Survey and Times Higher Education rankings) to determine quality of education and HEIs; increasing focus and allocation of resources on ‘employability’; and a sense that anxiety is produced, as Berg and others observe (2018), as a tool of control.

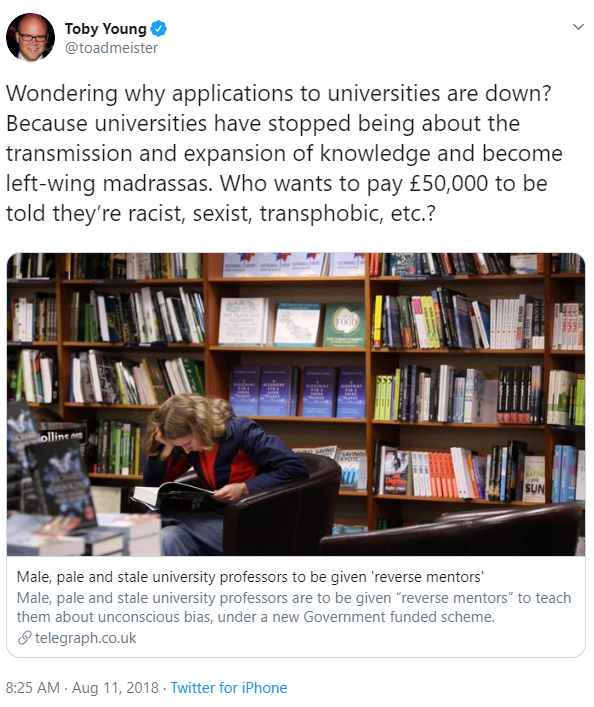

The OfS is another tool in the neoliberal toolbox. Competition within the neoliberal market is moderated by such regulators in the name of the consumer (in this case the student), but similar logic applies to supply of former public utilities such as water (Ofwat) and gas and electricity (Ofgem). Young’s experience of running one of the first ‘free’ schools fitted exactly within this neoliberal logic. His scorn for academics illustrates the concern that critics of neoliberalism such as Thomas Docherty (For The University, 2011) or the Edu-Factory Collective (Toward a Global Autonomous University, 2009) share; that control over the production of knowledge is now the new battlefront in late-capitalism. Shortly after his resignation, Young criticised universities as ‘left-wing madrassas’, implying also that they were concerned only to instruct students they were “racist, sexist, transphobic etc” (see tweet below) – a smear so ludicrous that even universities minister Sam Gyimah had to distance himself from the comment.

It is easy now to see in the campaign for Young’s resignation, certainly with the benefit of a review of ensuing events, a significant victory over a number of key institutions in neoliberalism.

Countering our apologist ‘colleagues’

Academia is not monolithic. It contains those with diverse political views. Unfortunately, some of the most senior figures, especially the stale, pale, middle-class males, tend to be the most conservative and yet their voices are often sought out by the media. This shapes policy and political responses. Take the following comment, for instance, from Professor Tim Crane, who was interviewed for The Guardian during the media storm over Young’s appointment: “I don’t think Young is necessarily unqualified for this position. Bodies like this typically contain people from many professional backgrounds.” This statement is typical of the stale, pale, middle-class male. It suggests Young may indeed be qualified. It hints that he has an appropriate professional background. Of course, what it fails to acknowledge is that there are other factors which make Young unsuitable, which should be determinative – but which Crane does not address. As someone who has been an activist in equality and non-discrimination issues throughout my professional life, it is inconceivable to encounter Young’s disparaging comments with reference to gender, social class, disability and sexual orientation but not wish to foreground these as relevant to the appointment. (I note the no-doubt unintended irony in Crane’s statement on his institutional webpage at the University of Cambridge that: “Professor Crane is currently working on a book on the representation of things that don’t exist”).

The apologists include those who adopted and continue to endorse concepts such as resilience and wellbeing, which in practice occlude the deeper structural and ideological causes of material disadvantage and the psychological and physical harms to individuals and groups. It becomes necessary for those of us opposed to neoliberalism to mobilise to counter the views of those who are effectively apologists for Tory placemen such as Young and for the discourses that support those like him.

Conclusions

The groundswell of academic protest against Young’s appointment presaged the wider opposition among members of UCU just over a month later during the USS strike. As Professor Gail Davies of the University of Exeter noted in a review of the testimonies from hundreds of people who took part in that strike: across articles, blogs and tweets, it was clear that for a large number of academics and others something snapped, changing relations within academia. That snap had its traces long before Young’s appointment. UCU had balloted its members on industrial action over the USS proposals on 29 November 2017. But concerns about changes within the higher education sector, including managerialism and commodification, had been circulating for years. When I stepped out of a full-time, continuing role in 2010, I subsequently recorded my concern with “the increasing commodification and managerialism of higher education in the UK” and the “related petty status-drives and ego-conflicts [which] distract from healthier engagement with those around us” (Meet Your Exec, page 4).

Part of this snap also reflects a fundamental re-think among academics about the objectives of the government. There appears to be a growing perception among academics that the current government is “determined to destroy higher education” and that this is being done through marketisation which is at odds with academics’ own view that they should be about public good.

As far as I can tell no-one has been held accountable for these failings. Barber remains chair of the OfS. Jarvis remains chief executive at UUK. The Tory chumocracy remains in government. In due course, the whole lot of them should be cleared out to make way for those of us who wish to uphold the highest public standards and secure for our universities the best for education and research rather than that which is driven by competition in a consumer marketplace.

UUK’s inaction reflects adversely on the organisation purporting to represent our universities. It is perhaps little wonder that when USS, another other serial avoider of grassroots views, sought to change our pensions so many went on strike or supported the strike with the hashtag #WeAreTheUniversity.

Myriad problems in the tertiary education sector that were identified before, during and after the UCU strike of 2018, remain. Some problems have worsened. We, however, have not gone away and we will not be quiet.

___________________

Some of the links in this article are to publications which publishers keep behind paywalls; which is, sadly, widespread practice in academic publishing. Some of these links allow temporary registration to access articles. Alternatively, some public libraries can arrange access to certain paywalled material. Apologies if you cannot access articles immediately.

.

© Dermot Feenan 2019