(Revised 20 July 2019)

15-minute read

Dermot Feenan

LLB MA LLM Barrister-at-Law FRSA

.

I came across an advertisement from the Public Law Project recently which troubled me. It advertised for unpaid Research Assistants.

The Public Law Project (PLP) is a charity based in London. It was set up in 1990 to secure public law protection for the poor and socially or economically disadvantaged in England and Wales. It engages in advice and litigation, research and policy work, and training. It’s done some good work.

However, the advertisement of unpaid Research Assistant roles is concerning. The research assistants are clearly conceived as part of the PLP’s ‘Programme’ of work. These posts are indispensable to PLP’s core activities, and the researchers appear to be expected to work on specific projects but they’re not paid. This is especially concerning when a number of bodies, including the Social Mobility Commission and Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs have publicly come out against similar unpaid (internship) positions. There is a wider range of concerns with these arrangements that I explore in this article. I’ve been a researcher myself. I know how demoralising it can be when you’ve worked to achieve qualifications and experience, and ploughed hard-earned money into your qualifications only to find that opportunities are limited to those who have the means to survive lack of income for prolonged periods by taking up such unpaid career-enhancing roles. That reality bites hard, as my own story also illustrates – but more of that later.

The nature of the posts

A Research Assistantship at PLP promises a number of benefits. According to PLP’s description of the role, it “provides the opportunity […] to develop […] research skills in a fast-paced environment”. The Research Assistant will be: introduced to the work of PLP; given appropriate credit for all work, and; carefully supervised. The assistant will be expected to share PLP’s core values and to work to high standards expected of PLP research.

PLP make no commitment to engage a volunteer for any period of time. Rather, they state that every such post “is determined by the circumstances of the project and the applicant, e.g. hours, length of overall commitment etc. will vary.” This formulation gives no specific information to a struggling working-class applicant to assess whether let’s say a four-week stint to gain much-needed experience before loss of income bites is worth the effort. Indeed, there is nothing in the advertisement that suggests that such an applicant could contact PLP to find out. Such arrangements are likely to favour those who have luxury of time and the absence of financial hardship.

Two of the current volunteers have evidently engaged in significant work for PLP to each produce a sole-authored research briefing for the organisation (Richardson, The gap between the legal aid means regulations and financial reality; Evenden, Legal aid and access to early advice). PLP clearly benefits from these briefings. They carry the name of the charity: they are not papers produced only under the researcher’s name or as part of a personal project. They are listed and available under ‘Research’ on the charity’s website, see below – showing the listing for the briefing by Richardson.

The core tasks for the Volunteer Research Assistants include:

- Assisting in the coordination and organisation of research activities;

- Contributing to the production of high-quality research in their areas including, where appropriate, assisting with desk-based research, literature reviews, data analysis, drafting of proposals and submissions, report writing and drafting of articles, social media content etc.;

- Assisting in the management and co-ordination of events;

- Attending meetings with external groups or partners, including government, legal profession and NGOs; and

- Working as part of a team with other researchers.

The work activity for a research assistant at PLP is not merely answering the phone, photocopying, filing papers, or the other humdrum tasks that might be associated in the minds of many with volunteering in an office. Moreover, the contribution that these researchers make to the work of the PLP suggests that the charity may be the primary beneficiary of the working arrangement.

This role profile and person specification for the research assistantship would ordinarily be expected of a salaried researcher in at least Grade 6 within universities in the United Kingdom. The role profile and person specification for the research assistant at PLP would be consistent with a starting salary of £27,000 approximately, at least.

When I have hired research assistants in universities, it has always been on the basis that they are paid according to national rates. These rates are known or should be known to any academic working in the higher education sector in the United Kingdom.

Risk of reproducing social inequality

Such unpaid positions tend to privilege the already-privileged; those who come from social classes where financial wealth, and social and cultural capital insulates or militates against material hardship and social exclusion. Such positions enable what the American sociologist Charles Tilly called ‘opportunity hoarding’ by the middle class (Durable Inequality, 1998).

It is perhaps no surprise therefore that the four current volunteers come from two elite universities: University of Cambridge and University College London.

The educational qualification for these Research Assistant posts is an LLM (Master’s degree) in law or related discipline, or equivalent experience. Most applicants who meet the Master’s criterion will already have done a primary degree, usually of three-years’ duration. Average fees for a three-year law degree in the United Kingdom are £27,000. Add subsistence costs, and the average undergraduate graduates with debt of over £50,000. Average fees for a full-time, one-year LLM are £11,000. Add subsistence costs, and the total comes to almost £25,000. So, the average candidate for the research assistantship will be saddled with a student debt of £75,000.

Volunteer or worker?

The ascription of ‘volunteer’ means the denial of any rights as ‘workers’ or ‘employees’, as legally defined. Yet, these research assistants are treated as indispensable for PLP projects. The language of employment is also used in the application materials. The Application Form for the role “Research Assistant (Volunteer)” states in the section on referees: “Your present employer will not be approached unless a provisional offer of employment has been made and you agree.” And, the Declaration section states: “I confirm that to the best of my knowledge the information given in this form is correct, that I am lawfully able to undertake this work, and that any information given can be treated as part of any subsequent contract of employment”. Moreover, the job advertisement states that they will be “under the management” of PLP’s Research Director. If these volunteers are in fact being treated as workers, this raises serious issues in law for PLP – which it might consider wise to resolve.

Concerns with unpaid internships

The Social Mobility Commission has repeatedly called for a ban on unpaid internships lasting more than four weeks. The call has been backed by the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Social Mobility, the Sutton Trust, and the Institute for Public Policy Research. A substantial majority of the public wish to see such unpaid posts banned. A survey by the Social Mobility Commission in 2017 found that 72 per cent supported a ban on unpaid internships of longer than 4 weeks. In 2017, the Taylor Review of Modern Working Practices said that “unpaid internships are an abuse of power by employers and extremely damaging to social mobility” (p. 91). Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs is cracking down on employers who engage interns as unpaid workers.

According to research conducted by the Institute for Public Policy Research in 2017, the number of internships offered by top graduate recruiters rose by as much as 50 per cent since 2010.

The former Chair of the Social Mobility Commission, the Rt Hon Alan Milburn, said:

‘Unpaid internships are a modern scandal which must end. Internships are the new rung on the career ladder. They have become a route to a good professional job. But access to them tends to depend on who, not what you know and young people from low-income backgrounds are excluded because they are unpaid. They miss out on a great career opportunity and employers miss out from a wider pool of talent. Unpaid internships are damaging for social mobility. It is time to consign them to history.‘

Such positions – whether called ‘internships’ or ‘research assistantships’ – if they amount to the same thing, exacerbate social inequality. They are most likely to exclude those who have no access to family accommodation. They are also likely to exclude those who live outside London, exacerbating geographic inequalities. The message that such unpaid posts sends out to young people is dispiriting. In a poll conducted by YouGov, published in December 2018, among 18—24-year-olds most said it was becoming harder for people from disadvantaged backgrounds to move up in society.

Given the high degree of precarity in both the research and the law labour markets, using the skills of a young research assistant without pay that does not add significant value to their employment prospects is especially egregious. Indeed, equipping doctoral students with adequate research skills to enhance employability was one of the reasons that the United Kingdom revamped training for doctoral students through the Concordat to Support the Career Development of Researchers. There is nothing in the description for the PLP post that indicates how research skills will in fact be developed by PLP.

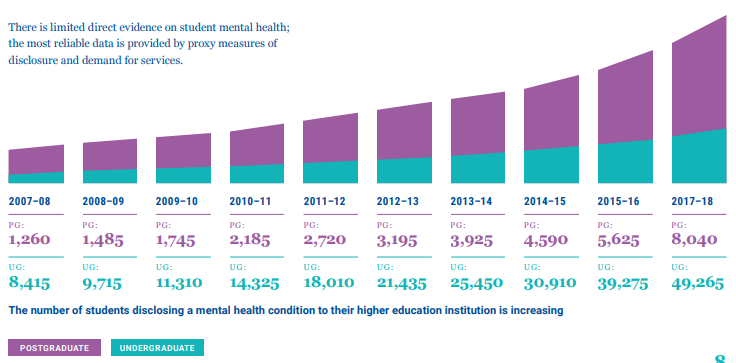

Unpaid posts such as research assistantships shore up job insecurity, which is associated with higher rates of poor health and suicide. A report by Universities UK in 2018 showed a steady increase in poor mental health among students at universities in the United Kingdom (see below).

The prevalence and adverse effects of unpaid internships led the EU Public Interest Clinic to submit, on behalf of The European Youth Forum, a complaint to the European Committee of Social Rights that unpaid internships (in Belgium) were unfair and discriminatory under the European Social Charter. The complaint, which has been ruled admissible, is awaiting deliberation by the Committee.

The recruitment of unpaid volunteers where this inhibits social mobility, reinforces class privilege, and contributes to inequality is a matter of social justice.

Could PLP do otherwise?

A number of other similar legal organisations have researchers. They are employed on a continuing basis or on fixed-term projects.

The Child Poverty Action Group, a long-established charity that, amongst other things, researches the causes of poverty, publishes guides on rights to benefits, and carries out legal work to establish and confirm families’ rights, employs two senior policy and research officers. It is a Living Wage Employer. It does not rely on volunteers.

The NLGN (New Local Government Network) advertised a 5-month Research Internship in autumn 2018. The post, for 21-hours per week, attracted the London Living Wage. The skills and experience required for the post were broadly similar to those required by the PLP. These included: a strong academic background and preferably a Master’s degree, and ability to work on different tasks and in a fast-paced environment.

Reprieve, a charity which fights for the victims of extreme human rights abuses, introduced a 12-month paid internship for the first-time recently. It worked with the Social Mobility Foundation to target talented people from less-privileged backgrounds. Their aim was to provide a stepping stone to a career in human rights or the legal profession. In addition, Reprieve works with four law firms to provide secondments to trainee solicitors. In addition, the organisation offers 12-month fellowships at its London office for graduates from the USA who have secured external funding and are eligible to work in the United Kingdom.

The Howard League, another charity, engages research assistance through its Research advisory group – which helps provide advice and support, including in environmental scanning and information sharing, and scoping and structuring research. The group comprises salaried academics working in the field of criminal justice.

The PLP isn’t poor. According to the Charity Commission, in the 2017/2018 financial year it had income of £1.7m, with £1.2m of spending; leaving a surplus of £500,000. And, since March 2016 income has exceeded expenditure by an average of 30 per cent per year. This leaves PLP with reserves. While these can be necessary for contingencies, no apparent consideration is being given to paying a living wage to research assistants. This is regrettable.

PLP has a number of paid researchers. Its Research Director, Joe Tomlinson PhD, joined as a lecturer in law from the University of Sheffield. He is now lecturer at King’s College London, and shares that role with the Research Directorship of PLP. There are other paid research posts at PLP.

PLP has already demonstrated creative ways to secure funding through its relationship with Lankelly Chase, a funder supporting frontline organisations that address how disadvantage clusters and accumulates, particularly homelessness, substance misuse, mental health issues, violence, abuse and chronic poverty. PLP has worked closely with a range of organisations to understand the barriers faced by their service users. It has, where appropriate, upskilled and assisted them to use public law to address systemic unfairness. The project received the assistance of two academics from University College London (UCL), Dr Lisa Vanhala and Jacqueline Kinghan, who acted as ‘learning partners’, to expand understanding of how public law can help effect systemic legal change.

PLP’s strategic aim to be proactive in engaging with universities, research centres, and any other organisations where mutually beneficial partnerships can be developed is important but it underscores the wider issue at stake – which is that the political economy in which many universities and research centres now work actively harms sustainable research and the livelihoods of researchers. The PLP should actively leverage its historically good reputation in order to engage in mutually beneficial relationships that support researchers properly. PLP currently receives considerable external funding from a wide range of funders (such as the Baring Foundation, Oak Foundation, and Esmée Fairbairn Foundation), to support its activities; principally for casework and legal advice.

I would encourage PLP to secure funding to ensure that its research assistants are paid.

There are good models of funders helping charities to do so. The Jack Petchey Foundation launched a new programme in 2018 inviting youth charities to bid for a share of a £200,000 fund to recruit interns and pay them the London living wage.

Impact of not funding researchers

Not paying researchers in such circumstances as outlined above has a number of effects. It appears to exploit the labour of workers. It degrades the labour value of researchers generally. It undermines the reputation of the employer. It perpetuates social inequality.

Not paying for these positions tends to privilege those who come from wealthy backgrounds. Public law can too easily lose the experience and insight of those who come from different social backgrounds; the very backgrounds that the PLP was initially concerned to ensure should be protected from disadvantage or discrimination. Such positions often provide a pathway into a legal profession that already disproportionately benefits the privileged. According to Rosaline Sullivan’s review for the Legal Services Board: “The expense of work experience and internships often creates obstacles to the nonprivileged.” Research by the Sutton Trust in 2018 found that Law had the second lowest rate of working-class unpaid interns (after finance).

The privileging of high-income candidates also has an indirect effect. Thomas Johnson, a law clerk in the USA, argues: “preventing low-income applicants from developing a taste for altruism will hurt nonprofits in the long run by discouraging these individuals from joining the nonprofit sector” (p. 1156).

Using volunteers to perform jobs that could be done by paid staff is also likely to make other workers anxious for their jobs. Failing to pay even expenses to research assistants when employees are paid a salary and are likely to be able to afford a decent lunch perpetuates economic stratification and inequality at a fundamental level.

It would be no answer to say, “but these are simply volunteer posts, volunteering is a good thing”.

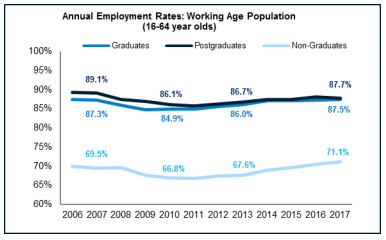

Decently-paid jobs are needed for an expanding workforce suffering from insecurity and precarity. There are low rates of employment among postgraduates in the United Kingdom, at 12.3 per cent in 2017. Shortly after the global financial crisis in 2008, the gap between rates of employment for graduates and postgraduates narrowed and has been virtually indistinguishable for the last five years as a result of stagnation in the labour market (see below). Unpaid volunteer posts of this nature harm researchers.

There is increasing concern about the growing extent of precarity for researchers in the United Kingdom. The union for staff in higher and further education in the United Kingdom, UCU, now has an Anti-casualisation Committee in recognition of the problem. Qualified researchers, many with doctorates, throughout the country struggle to make ends meet or even continue their research careers because of the developing reliance by employers on fixed-term or hourly-paid contracts. Advertisement of unpaid research posts exacerbates the problem.

The perpetuation of such working arrangements is incompatible with broader initiatives, such as those taken by the Living Wage campaign, Social Mobility Commission, and the Low Pay Commission, to ensure that workers receive enough to provide for themselves and their families.

It’s not good enough for a body committed to broadly progressive social justice issues to treat workers like this.

I write this as a socio-legal academic who has not only worked in full-time employment but who has struggled financially as a result of increasing casualisation. But I am also concerned with the prospects for the thousand-plus students I’ve taught, scores of whom are capable of research and who would struggle to take on unpaid research posts because they don’t come from wealthy backgrounds. And this is where I return to my own story.

Years ago, I had to forego a research degree offered to me at the University of Oxford because I couldn’t afford to financially support myself throughout that period. My parents were not rich. My father had just been made redundant and had recently undergone treatment for life-threatening illness. He and my mother struggled to support three children. This had a significant adverse impact on our family. Instead of going to Oxford, I had to apply for a state bursary to undergo professional training and then a fees-and-subsistence scholarship to undertake a postgraduate degree elsewhere. And during that degree, when I encountered unexpected financial hardship, I was helped by that university to cover additional expenses. I had to forego my Oxford position. They had no ability to respond to the hardships I unexpectedly faced. While that undoubtedly closed some doors subsequently, it did not prevent me from returning to Oxford years later as a visiting scholar or from working at other times on projects with many researchers at Oxford. I’ve never forgotten, though, the generosity received from the state and, especially, from that other university (which will benefit under my will). Many of the working class and struggling students I’ve taught became researchers, and, they, too, will face the same challenges of trying to make their work pay.

None of the foregoing is intended to dismiss the importance of volunteering in the abstract. Volunteering can be a social good. It can consolidate humanitarianism. It can also enhance individual health through pro-social behaviour. I’ve volunteered happily for loads of charities and through public service, including for Amnesty International and a Citizens Advice Bureau. However, volunteering shouldn’t allow organisations simply to benefit from a system of cheap labour when other staff are well-paid, the organisation has (or could arrange) funding, and failure to pay has broader social costs, such as perpetuating inequality.

It is possible that some charities are unaware of the distinction between worker and volunteer despite the considerable attention that has given to the issue of unpaid positions. The Sutton Trust found in 2018 that: “There is substantial confusion on the law as it applies to unpaid internships. Almost half of graduates (47%) thought unpaid internships were ‘legal in most situations’ or weren’t sure. When provided with a series of scenarios, around a third of employers didn’t know whether the situation would be legal or not, and up to 50% incorrectly thought a scenario where an intern was being paid under the national minimum wage was legal” (p. 5).

My own research shows that research managers can be ignorant of the conditions in which those who supply research data operate. Koldo Casla, Policy Director of London-based national charity Just Fair, which monitors and advocates for the protection of economic and social rights, informed me he relies on volunteers for their research, specifically from ten students engaged at human rights clinics at SOAS and the University of Birmingham. Just Fair liaises with lecturers they often work with at those universities, and asks them to “gather a team”. While he informed me that the students were not formally contracted, when asked how many hours each student worked he informed me that Just Fair “don’t control that. I wouldn’t be able to tell you”. “I supervise the adverts. So, I discuss the substance of the research with them. The person who is doing the logistics, the day-to-day stuff is my colleague [the Operations Manager],” he added.

Just Fair has only three members of staff who operate out of one office. The way in which student labour is used without knowledge of their conditions is one side to the same coin by which the PLP can appoint a part-time, but paid, academic director to hire unpaid student volunteers. They are part of the shifting economy in the United Kingdom (and elsewhere) that increasingly relies on unpaid labour. The phenomenon was well set out by Ross Perlin in Intern Nation, his exposé of internships in the USA, whereby organisations abused the free labour of college students – generally with the connivance of the universities themselves.

A call to action

I call on the PLP to pay its Research Assistants the London Living Wage and to ensure that any future advertisements make clear the time commitment required so that able candidates who may be struggling financially are enabled to decide in an informed way, consistent with their life circumstances, whether or not to apply.

Other organisations should also look to their recruitment policies and practices, consider their wider impact, and, if indicated, help end inappropriate unpaid-work culture.

.

© Dermot Feenan 2019