9-minute read

Dermot Feenan

LLB MA LLM Barrister-at-Law FRSA

.

The Belfast Rugby Rape Trial reveals the persistence of deeply traditional, troubling views about women in Northern Ireland, the challenges for women in seeking justice against sexual offenders, and the importance of grassroots responses from women activists and scholars.

There is a line in Terrence Rattigan’s The Winslow Boy in which a central character is asked whether justice was done in court. He replies: “Easy to do justice. Very hard to do right.” This contrast between justice and morality often recurs in thinking hard about law.

The relationship features in much discussion around the recent rape trial of two rugby players in Belfast, Northern Ireland. While the players were acquitted, widespread activism in support of the complainant and against sexism and misogyny rapidly developed.

The trial and surrounding circumstances reveal two continuing disturbing truths about gender in Northern Ireland: first, commentary still reveals deeply traditional and troubling views about women, and secondly, and following from this, non-governmental and non-legal means of addressing gender concerns remain vital and important.

The trial and its aftermath

Paddy Jackson, 26, and Stuart Olding, 25, who both played rugby for Ulster and Ireland, were found not guilty on 28 March of rape at a party at Jackson’s house in the early hours of 28 June 2016. Jackson was also found not guilty of a further charge of sexual assault.

Lara Whyte notes that the case, subsequent acquittal and an ongoing joint review of the players’ behaviour by the Irish Rugby Football Union (IRFU) and Ulster Rugby attracted huge interest, protests and accompanying backlash.

Part of the interest lay in a series of messages shared between the players which were reported as part of the trial proceedings. Olding messaged in a WhatsApp group the morning after the party: “we are all top shaggers” and “there was a bit of spit roasting going on last night fellas”. Jackson replied: “There was a lot of spit roast last night”. Olding responded to a friend who asked about the complainant: “she was very very loose”.

On 14 April 2018, the IRFU and Ulster Rugby stated that “following a review” they “have revoked the contracts” of Jackson and Olding “with immediate effect”. It added: “In arriving at this decision, [we] acknowledge our responsibility and commitment to the core values of the game: Respect, Inclusivity and Integrity.”

The statement concluded: “It has been agreed, as part of this commitment, to conduct an in-depth review of existing structures and educational programmes, within the game in Ireland, to ensure the importance of these core values is clearly understood, supported and practised at every level of the game.”

Traditional, troubling views about women

The case and its aftermath revealed a breadth of predictably overt derogatory and hateful views about women. But they came freighted with subtler attempts to ignore or diminish the significance of the players’ conduct, to consign it to the past, and to effectively erase the diverse concerns of many people from different individual and organisational perspectives. These are not techniques unfamiliar to those who have studied the struggles in the north of Ireland to deal with the legacy of the recent period of violent political conflict, often euphemistically called ‘The Troubles’.

As someone who grew up and played sport in the north of Ireland, I know only too well the casual misogyny that exists. Later, I worked for a time there as a therapist. I was astonished to encounter so many women clients who had been abused physically, sexually and psychologically, in addition to their coping with the trauma that many of us who lived through the conflict experienced. I say ‘astonished’ because, the government, media and culture generally make it difficult to see and understand the nature and pervasiveness of this abuse. As male in such a male-dominated society, one’s way of experiencing, and not-experiencing, is shaped necessarily by gendered socialization – though the effects are not immutable.

In the week after the verdict, the media reported the view of one Willie John McBride, a former Ulster and Ireland rugby player. McBride said Jackson and Olding had “learned their lesson” and were “not bad young men”. He added: “When alcohol is in, and common sense is out […] it is very sad that they have all got caught up in this.” He concluded: “it is time they got back to doing what they do best and that is playing rugby.” McBride is President of the Ulster Rugby Supporters Club. He was described in the media as a ‘legend’. He may not be unaware of the authority this provides. But the media also provide a platform.

Noeline Blackwell, chief executive of the Dublin Rape Crisis Centre said in response to the comments by McBride: “They don’t seem to recognise that the behaviour of some of the most prominent rugby players in the country was extraordinarily disrespectful and failed to take any account of the humanity or dignity of the young woman involved.”

Some other commentators in the rugby case castigated ‘feminists’, whether they identified as such. Some saw the protests as attempts to impose feminist ‘worldviews’ on men. Some engaged in false equivalence between the acquittal of the men and their innocence generally, without recognising that a finding of not guilty pertains to a specific charge only and does not address broader behaviour.

But even journalists who might normally bring incisive analysis to bear failed to confront head-on the misogyny, call it out or do the much harder work of exploring how it might be put right. One sought to explain away the ending of the players’ contracts in terms only of the bad publicity reinstatement would attract; another blamed the prevalence of pornography – any explanations instead of sexism and misogyny.

Yet others attempted to lump all viewpoints antithetical to their own as the view of the ‘mob’, without recognising the reasonableness of opposing views or the diversity of those views.

The rapidity of social media responses, in all their variety, in support of the complainant and women generally created a steady flow of perspectives, unmoderated by news media, institutions, and authority figures, especially men. While some of the responses were viciously defamatory, and even appear illogical, there is also a distinct impression of multiple perspectives: sharing and diverging, testing-out and refining viewpoints, sympathetic towards the complainant and/or survivors of rape and sexual assault more generally. Social media supports existing activism but also constitutes its own form of activism.

Many women and men saw the case as a struggle between different, conflicting and incommensurable, versions of belief. At one level, the jury decides unanimously that the men are not guilty. In contrast, many choose to believe the complainant and, therefore, do not accept the jury verdict. This latter view offends against the presumption of innocence, and the associated concepts of a fair trial and judgement by a jury of one’s peers.

There are, however, other senses in which belief in and about the complainant seems to operate in ways that may not be amenable to resolution through existing law or adjudication. These ways are about support for a woman who persists despite the odds. They are about sympathy for a woman who is demeaned, whose vagina was – allegedly – torn, who is described by one of the players as leaving in hysterics and who is thrown home. She is believed because her experience resonates with the experience of many women.

In the year up to 31 March 2018 (three days after the verdict in the trial), the Police Service of Northern Ireland recorded 3,443 sexual offences, up 9.3% on the previous year. There was a 17.8% increase in the number of reported rapes. Yet, less than 2% of these reported rapes result in a conviction (with the comparable rate in England and Wales around 6%). Experience (and/or fear) of sexual offences, including rape, cannot be separated from women’s experience of gendered abuse of power generally – including ‘domestic abuse’. In the same period, 14,560 domestic abuse crimes were recorded – the highest level since 2004/2005.

The challenges that many women face in securing legal redress against sexual offenders are huge. As Professors Clare McGlynn and Vanessa Munro observed in the introduction to their edited collection Rethinking Rape Law, “spurious and highly gendered ‘rape myths’ continue to inform both the popular and penal imagination; and rape complainants who make it into the courtroom often still endure invasive and hostile questioning from defence counsel.”

It seems plausible that the reaction to the threat by Jackson’s solicitor against those who used the hashtag #IBelieveHer may have drawn from this aforementioned sense of belief in the complainant. Jackson’s solicitor’s treatment of the hashtag as implying that his client was guilty may have missed this more complex context – though it is clear that some users of the hashtag clearly did use it to contest the jury’s verdict. Such polarity of view unsurprisingly gave rise to the counter hashtag #IBelieveThem, which, in the rapidly shifting trends of Twitter was ‘squatted’ by those who pluralised it to mean “we believe women”. Social media became a field of recurring contest.

The case became a lightning rod for broader concerns. Legal threats to sue for defamation misjudged that phenomenon. That the threats came from a man, on behalf of a man accused (and just acquitted) of rape, and against protestors (who in fact were largely girls and women) probably exacerbated the misjudgement and very likely prompted the wave of people who then adopted the hashtag #SoSueMePaddy.

Effective sanctions?

It is reported that the players entered into a severance agreement. If so, it is likely that they will have signed a non-disclosure clause. The absence of any disciplinary sanction against Jackson and Olding may leave some feeling that an element of justice was missing.

Jackson said after the trial that he apologised unreservedly for “degrading and offensive” WhatsApp conversations about the incident. Many pointed out that Jackson did not apologise until many days after the trial ended, and that the apology coincided not only with the issue of the statement by the Bank of Ireland but the ongoing IRFU and Ulster Rugby review.

What is lost in settlements are opportunities that broader inquiries can take about pervasive behaviour, and systemic or institutional problems. Sometimes, these can originate in incidents involving one victim. They can produce findings that not only address the institution most directly responsible but lead to profound changes further afield – as occurred in the Macpherson Inquiry into the investigation into matters arising from the murder of black teenager Stephen Lawrence in 1993.

The inquiry report not only criticised the Metropolitan Police but in naming the concept of institutional racism led to profound change in awareness of the need for change in service delivery.

It is troubling that in the wake of the Jackson and Olding acquittals, a photograph appeared of two players from Malone Rugby Football Club each wearing names ‘Stuart Olding’ and ‘Paddy Jackson’ with a trophy between their groins. The photograph was taken in the changing rooms of Kingspan Stadium, the home of Ulster Rugby, after Malone won the McCrea Cup.

The trophy is held horizontally, its neck and base opening directly in front of the groin of each man respectively. In view of the widely-reported messages at trial regarding ‘spit-roasting’, the image mimics and valorises Olding and Jackson. It suggests that Olding and Jackson got their ‘trophy’ that night – with all its equally misogynistic connotations.

There is clearly a wider culture of disrespect here in rugby.

Indeed, in 2012, Jackson – then playing for Ireland and Ulster – was caught on camera with other Ulster Rugby players posing ‘blacked up’, apparently as a slave as part of an “Olympic-themed fancy dress party”. Then, Ulster Rugby apologised “unreservedly for any offense”. It added: “it was not the intention of the players to cause upset”. I have found no report of Ulster Rugby taking any disciplinary action against Jackson or other players.

Non-governmental, non-legal solutions

In the days after the verdict, protests took place in Belfast, Cork, Derry and Dublin. While protestors focused on demonstrating solidarity with the complainant – through chants such as ‘We Stand with Her’ – they drew also upon the #MeToo response to sexual harassment and concerns regarding law on abortion north and south of the border. An advert in the Belfast Telegraph newspaper on 6 April called for Jackson and Olding to be dropped. Initiated by Lara Whyte and others, it was paid for in a matter of days through crowdfunding. The Belfast Feminist Network separately set out five demands including non-reporting of rape trials until verdict, relationship and sexuality education (including consent and toxic masculinity), and addressing the blaming and shaming of victims. It also protested outside the home of Ulster Rugby on 13 April.

This surge in activism is not unusual. Women played a key role in community organising throughout the conflict. The absence of a functioning Assembly since January 2017 has renewed grassroots activism. Claire Pierson, Lecturer in Politics, notes of Northern Ireland, “it is often left to women’s groups and activists to lobby for legislative change and better policy and policing responses to gender-based violence.”

Some of those concerned about the players’ behaviour undoubtedly also understood the legacy of misogyny and violence that characterised the experience of many girls and women during the conflict; revealed through the pioneering work of Professor Monica McWilliams’ in the 1990s and carried on today by activists such as Kellie Turtle, academics such as Drs Catherine O’Rourke and Aisling Swaine, and others. If the complainant, whose identity remained anonymous in the trial (despite an unlawful breach outside), was constrained by the rules of evidence in what could and could not be said, many women outside the court decided to communicate freely and openly. They stood in for an anonymous complainant, becoming collectively the universal Complainant.

As grassroots protest began to build after the trial against the reinstatement of the players, an online petition to the IRFU to conduct a review of the players’ ‘behaviour’, gathered over 65,000 signatures. A survey in Ireland by Amarach Research reported on 9 April 2018 that 55% of people would not like to see Jackson and Olding play for Ireland again. Only 26% said they would like to see them do so. When the IRFU and Ulster Rugby issued their statement on 14 April 2018, the online petition had attracted over 70,000 signatures. A counter-petition calling for the players’ reinstatement had attracted only 16,000 signatures.

Economic pressure aimed at changing behaviour in scenarios such as this can often be decisive. The reported intervention by two of the decision-makers’ principal sponsors is likely to have played a part. The official shirt sponsor of Ulster Rugby is Bank of Ireland, whose new chief executive, Francesca McDonagh, has reportedly been at the forefront of the gender equality agenda in recent years. On 11 April 2018, Bank of Ireland, expressed concerns pending completion of the review with “the serious behaviour and conduct issues” raised in the trial and said it “expect[ed the] review to be robust”. McDonagh was reportedly personally involved in approving the statement. The official shirt sponsor of Ireland is Vodaphone Ireland. Its chief executive is Anne O’Leary. The achievement of power by women at corporate sponsorship level may help correct any male bias in a sport otherwise dominated by men.

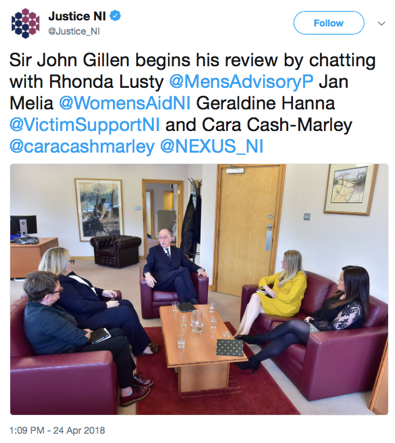

A week later, on 17 April, the Irish News, one of the north’s leading newspapers, carried an open letter signed by, among others, Women’s Aid Federation Northern Ireland, calling for an immediate independent review of how the criminal justice system handles sexual violence cases. The next day, BBC Northern Ireland reported that such a review was expected; with arrangements confirmed by the Department of Justice on 24 April. The Department’s Twitter announcement features four women representing four organisations, with Sir John Gillen, the review chair.

Following rumours that month that English rugby club Sales Sharks were ready to sign Jackson and Olding, local MP Barbara Keeley stated that it would send “entirely the wrong signal to fans and to the local community.” The End Violence Against Women Coalition, which includes Women’s Aid Federation Northern Ireland, reiterated its demand that the players should never be allowed to play rugby again. It was announced on 28 May and 8 June that Olding and Jackson respectively had been signed by clubs: in France, a long way from home.

Throughout the trial and in its aftermath, the preponderant voice has been of women seeking that Jackson and Olding not be reinstated and for interventions to address sexism and misogyny. In the words of one protestor, the complainant may have lost a battle but she won the war. In such dyads, between justice and morality, between battles and war, we see an enduring conflict involving gender, and, here, the denouement suggests that, with collective voice, the Complainant may have prevailed somewhat.

.

© Dermot Feenan 2018