7-minute read

Dermot Feenan

LLB MA LLM Barrister-at-Law FRSA

.

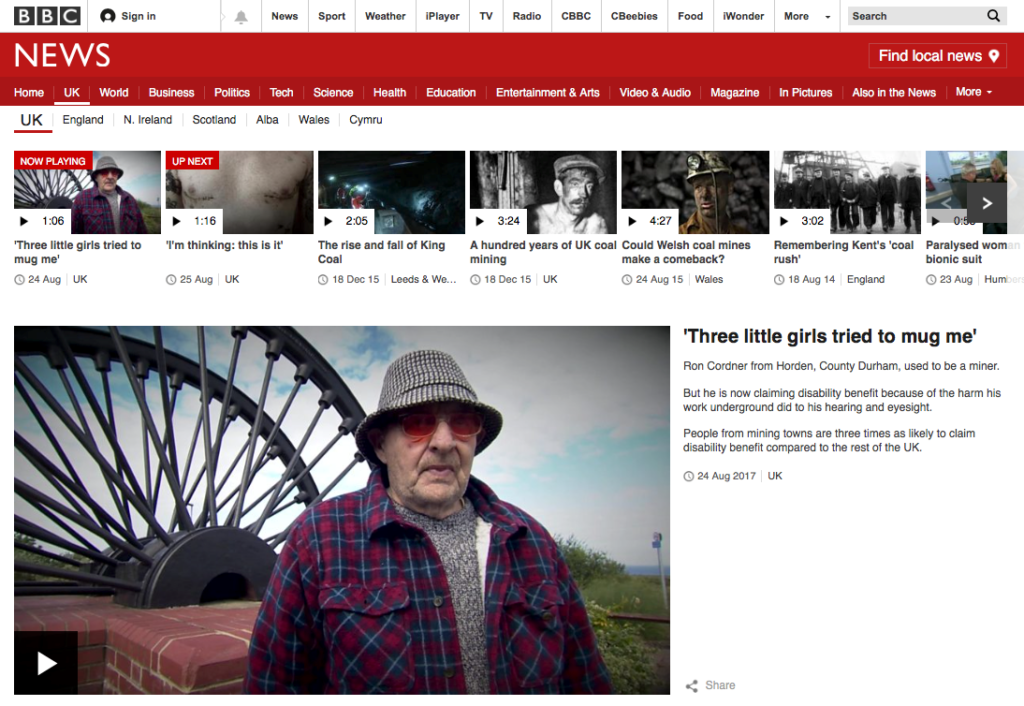

On 24 August 2017 the BBC broadcast a video. By the evening of Saturday, 26 August 2017 it was momentarily the most-watched video on the BBC News website. It’s title: ‘Three little girls tried to mug me’.

The video is one minute and six seconds long. It features Horden, a village in County Durham in the north east of England. The video focuses on Ron who worked for nearly 40 years in the local coal mine. After an aerial view over Horden, the video cuts to the silhouette of the statue of a miner. Subtitles explain: ‘At its peak, 90% of the people who lived here worked in the coal mining industry.’

So why the reference to three little mugger girls?

The video informs us: ‘If you live here today, you are three times more likely to claim disability benefits’. Then, the video cuts to Ron. He stands facing the camera with a memorial to the colliery behind him. “There’s nothing in this area for us. Nothing”. He tells us that he “gets depressed and tried to commit suicide”. Ron is shown walking. The subtitle informs us that he worked in the coal industry for nearly 40 years, adding: ‘His life underground left him with severe hearing loss. Now, he is also registered blind.’

In the next shot the camera shows a series of terraced houses in Horden, with the text below: ‘As a miner, Ron walked these streets with pride. Now he no longer feels part of his own community’. The camera descends to just above roof level showing a pavement in front of houses. We hear Ron’s voice and his words appear in text at the bottom of the frame: “Three little girls, no older than 10, tried to mug us”.

We don’t know exactly what happened: what was the nature of what Ron refers to as ‘mugging’ or whether the matter was reported to the police, even if one sets aside the problems associated with the fact there is no offence of ‘mugging’ in English law and criminal responsibility starts at 10.

What is noteworthy is not that Ron experienced this as distressing: it is that the BBC chose this title and quotation for a video that uncovers things rotten in the state of England. At one level, we have the reference to high rates of reliance on disability benefits, a former miner’s industrial injuries, and his depression and attempt at suicide. But there is the unexplored context of the economic and social deprivation of a community eviscerated in the 1980s by the government of Conservative Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher through an ideological programme of largely free-market economics accompanied by intent to erode the power of the unions. We are instead presented with the clickbait sensationalist headline of an attempted alleged mugging by ‘little girls’.

The BBC headline plays into a series of familiar tropes in the UK that demonize working-class communities. The first trope is that of the dangerous child.

A survey commissioned by the children’s charity Barnardos in 2008 found that 49% of adults believed that children pose an increasing danger to society. The UN Committee on the Rights of the Child was sufficiently concerned to recommend in 2008 that the UK take ‘urgent measures to address the intolerance and inappropriate characterization of children, especially adolescents, within the society, including the media’. This stereotype of the dangerous child, fuelled by the media, has a long history of harming working-class communities.

An alternative or at least more expansive way of understanding childhood in Horden might have been to address child poverty. According to End Child Poverty, Horden has one of the highest rates (35.29%, after housing costs) of child poverty in the UK; it neighbours wards which are among those with the highest rates of child poverty in Britain, including Peterlee East (39.81%).

The first trope in the BBC video is related to the second, that of the criminogenic neighbourhood. Yet official data shows a low level of crime in Horden. Notwithstanding, a dangerous criminality is conveyed by that significant image of three little muggers. Professor Stuart Hall and others noted in 1978 in Policing the Crisis, that the term ‘mugging’ becomes not only an index for disintegration of the social order but, as an “ideological conductor”, serves as a “mechanism for the construction of an authoritarian consensus, a conservative backlash”. The brunt of such authoritarianism falls on the working class, who must be degraded to legitimise their treatment – the working class is presented as a dangerous underclass to the stable middle class.

The criminality narrative coheres with a distinctive ideology that blames individuals and refuses to recognise the political and socioeconomic factors that influence behaviour. A recent illustration of such a narrative was the response of David Cameron, former Conservative Prime Minister, to the widespread civil unrest in England in 2011. He described the disturbances as common or garden thieving, robbing and looting”. Research by academics at the LSE noted that the riots did not happen in a political vacuum: many rioters spoke of protesting because they felt that the police treated them like criminals regardless of what they had done.

The insinuation of criminality in, and a lack of empathy towards, mining communities by the BBC has form. During the miners’ strikes of 1984-1985 the BBC engaged in imbalanced reporting, particularly in its coverage of the Battle of Orgreave. An internal report from 1985 obtained through Freedom of Information law included the comment of one BBC local radio news editor who bemoaned “the apparent television hunger for violence on the picket line at the expense of greater understanding”.

Ron talks of depression and attempted suicide. The BBC report does not explore the reasons for the depression and attempted suicide. We are not told whether Ron is in receipt of disability benefits for deafness and registered blindness, though these are conditions which would warrant entitlement.

Claimants have faced changes and reductions in benefits under the Conservative government. In 2016, the UN Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities conducted an investigation into the UK’s obligations. It found “grave and systematic” violations of the rights of disabled people. It concluded that evidence was available to the Conservative government that such welfare reforms would “disproportionately and adversely affect the rights of disabled people”, yet the government not only ignored this evidence but pressed ahead with the reforms.

We are told nothing in the BBC video of Ron’s capacity to travel beyond the narrow streets of Horden. We see him walking, in one image with a guide dog. But beyond these streets how might he get around: to see friends, family and former colleagues; to socialise; to contribute to his community; and to enjoy the many amenities that have moved now to outlying towns? In 1905, a railway station opened at Horden to serve the growing town. In 1963, Horden was one of a number of railway stations identified for closure in the Conservative government-commissioned report The Reshaping of British Railways. The government sought to ensure that British Rail made a profit. The station closed in 1964. The closures not only failed in their attempt to eliminate losses but lead to a belated recognition that the railways serve a social role, including providing vital links to cities and employment opportunities, which should be financially acknowledged.

Alarm bells were ringing for Horden much earlier than the BBC’s video. In February 2015, Channel 4 reported that such was the collapse in home occupation that a local housing association, Accent, offered to sell 130 terraced properties to County Durham for £1. The council declined. Gordon Perry, Chief Executive at Accent, attributed the collapse to the ‘bedroom tax’ (or ‘spare room subsidy’). Introduced by the Conservative government in 2013, it allowed a cut to housing benefit where the recipient occupied public housing with a spare room.

Perry said, “previously we had 67 per cent of our two-bedroom properties had single people in. But bedroom tax means that that is no longer affordable”.

“£57 people get on benefits, that’s pretty difficult to live, if you’ve got £10-£14 of bedroom tax on top of that, it means it’s impossible,” he is reported as adding. And yet, 11,000 people were on the waiting list in County Durham for social housing.

The incremental departure from each home cumulatively makes this former community less attractive. It illustrates how abstract political economic models that fail to take account of how people really live and what makes communities survive, can end up damaging those lives and communities.

Journalists able to provide depth and context try to make sense of information that instead became in this BBC video merely visual-soundbites.

By contrast, on Sunday, 27 August, journalist Mark Townsend, writing in The Guardian published a story titled ‘”People are starving”: village life in Britain’s blighted coalfields’. Townsend reported on Horden. The quote in the title of his story comes from Paula Snowden, who runs the Horden Hub community centre. Snowden describes malnourished families begging for food. “Most had received benefit sanctions and were basically starving when they came to us”, she said.

A report by Professor Rachel Pain at the Centre for Social Justice and Community Action at Durham University in 2016 noted that notwithstanding deprivation in Horden, it has especially strong community assets. The report referred to the village’s strength of voluntarism. “Horden’s heritage is a resource rather than a hindrance, leading to strong community spirit, identity and pride”, it added. The report concluded that ex-industrial areas like Horden require additional support and financial resources to help residents to protect and sustain these assets and improve life for others.

Funding for the creation of the Hub was provided in part by The Coalfields Regeneration Trust. Many members of the Trust’s board are former miners and union members. The Trust’s vision is for the former coalfield communities to be “sustainable, prosperous, viable and cohesive without support”.

Local Labour MP, Grahame Morris, has contributed to securing support to get a new railway station by 2020. “It will be a big boost for jobs, for regeneration, for what we are trying to do with housing in Horden”, he said.

Horden thrived on the colliery that was established in 1900. In 1935, the colliery employed 4,432. In its time Horden contributed to production of coal at a critical time in the UK’s industrial past, sustaining the country during the Second World War. Its workers gave not only their labour but also their lives. Records show 167 fatalities at the colliery. Many more suffered work-related injuries or died later from conditions arising from their work in the mine. By 1985, the number working in the colliery had dropped to 2,033. The colliery was closed by the National Coal Board in 1986. It was not because the workers were not productive or hard-working. While output from the mine had reduced due to regular water ingress, it was one of scores of collieries targeted for closure by Margaret Thatcher’s government.

At the end of the BBC’s video, Ron says: “Sympathy I don’t require. Show me some respect. And a little bit of help. And most of all some understanding”.

The BBC might have titled the video differently, using another quote from Ron that could also have resonated with a wider range of issues: ‘Show me some respect’. We should not perhaps be surprised by the BBC’s failure to provide socioeconomic context that might trouble conservative policies. A report by Cardiff University in 2013 found that the BBC consistently granted more airtime to Conservatives whichever party is in power. It noted that on BBC News at Six, business representatives outnumbered trade union representatives by more than 5:1 in 2007 and by 19:1 in 2012.

Poverty and social disadvantage will never be overcome by demonising children, criminalising communities or ignoring the socioeconomic causes of deprivation. Ron’s call for help, understanding and respect isn’t served by such broadcasting.

The future for generations in Horden was stolen by an ideological experiment in free-market economics by Margaret Thatcher’s government, exacerbated for a current population robbed by Conservative-led welfare cuts. The truth about Horden’s deprivation is filched by journalism that ignores deprivation’s political and socioeconomic causes. Who are the real muggers in Horden?

.

Acknowledgement

Thanks, as always, to Karen Bensusan for her love, support, and assistance.

.

© Dermot Feenan 2017