7-minute read

Dermot Feenan

LLB MA LLM Barrister-at-Law FRSA

.

Cable Street runs from Royal Mint Street to Butcher Row through London’s East End. To the south lies the Thames, and its great, former working docks: St. Katharine and London.

Eighty years ago it witnessed one of the most decisive defeats of fascism in Britain in a show of solidarity among minority ethnic groups, members of the Jewish community, organised workers, and communists.

In the early 1930s this area of the East End of London was targeted by Sir Oswald Mosley’s fascist Blackshirts. Mosley had created the British Union of Fascists (BUF) in 1932, influenced by Mussolini’s fascism in Italy.

The BUF had a paramilitary wing. Its uniform – borrowing from Mussolini’s fascist squadristi – comprised a black shirt; hence the moniker ‘Blackshirts’. They aped the raised hand salute of other fascists in Italy and Germany.

It is perhaps easy to dismiss their fascism as of historical interest only, of no relevance today. But the fascism emerged out of profound disillusionment with the existing political status quo during the economic hardships of the late 1920s. It fed off an ultra-nationalism. Today, the rise of anti-immigrant language by government ministers, politicians and sections of the media, plus significant increases in hate crime, in the wake of another economic crisis, ring alarm bells.

The rise of fascism

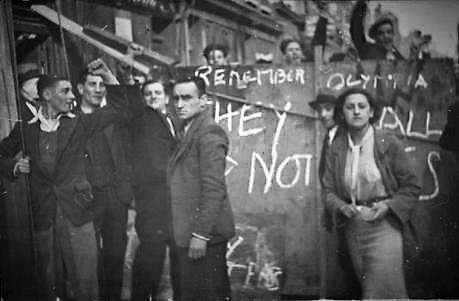

By 1934, the BUF began to embrace anti-semitism. Violence by Blackshirts against protests by anti-fascists at Olympia in London had led to widespread revulsion. Yet, as fascism had taken hold in Italy and increasingly in Germany, Mosley planned a series of marches for 4 October 1936 through the East End of London.

The area north of Cable Street was then a predominantly working-class district of Jews engaged mainly in manufacturing and tailoring. Many of the Jews of the East End were refugees from the pogroms of Tsarist Russia, the Baltic States and Poland. South of Cable Street, many of the dockers were Irish migrants. The Great Depression of 1929-1932 struck hard in the East End. Mosley’s BUF opposed the traditional sectarianism between Protestant and Catholic. Overcoming that old schism, which had blighted Ireland for centuries, appealed to many Irish workers. But, as in many struggling communities fearful of losing their foothold in precarious times, it was not uncommon to see signs ‘No Jews on Our Street’. However, reciprocal relations had nonetheless been established across religious and national lines of identity.

In 1889, a series of strikes led to a group of Jewish tailors organizing a stoppage. Though the docks were monopolized by the Irish, a dockers’ Strike Committee financially supported the tailors. In late April 1912 German Anarchist Rudolf Rocker helped the Jewish tailors in securing shorter hours, no piecework and better sanitary conditions. When many of the dockers’ families experienced hardship from the strike, Jewish trades unions and local Anarchists organized a support committee, and Jewish families took in over 300 of the dockers’ children. The solidarity was not forgotten over 20 years later.

The battle

On 4 October 1936, the BUF planned ‘four columns’ to march through the East End culminating in speeches. The Home Office rejected a petition from over 100,000 people in the East End to prevent the march.

The BUF gathered along Royal Mint Street, escorted by 3,000 police. However, tens of thousands turned out to block the march.

Less than 3 months earlier General Franco invaded mainland Spain from Morocco to overthrow Spain’s elected Republican government, leading to the Civil War. Dolores Ibárruri, the Communist leader, opposing the invasion said: “The fascists shall not pass! They shall not pass!”. It became a rallying cry for anti-fascists at Cable Street.

Barricades were built.

The police tried unsuccessfully to disperse the crowds, though many were arrested and injured, some in repeated police baton charges.

When it became clear that the march could not be forced through except with serious disorder, it was banned by the Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police.

Continuing significance

Eighty years on, the Battle of Cable Street has passed into political folklore on the left. Its commemorations have served as a gathering point for anti-fascists.

The battle showed solidarity with a vulnerable minority population, then migrant Jews. It confronted those who use or would seek to use their power to intimidate and cow others. It underlined the value and power of labour solidarity.

Max Levitas, one of the speakers at the 80-year commemoration was then a Young Communist. Now 102, and still living in the East End, he recalls: “Mosley and his fascists wanted to take over the East End […] To run out the Jews and communists. We had to stop them. It was the people, united, fighting together.”

The Battle also showed the importance of internationalism. It just happened that the then vulnerable population of the East End was Jewish. But the Irish, too, had then experienced discrimination. The docks had been settled in turn by those brought back by Britain’s imperial trade, including South Asian lascar seamen, and Chinese and Greek sailors – who married into the settled community.

The Battle remains significant, especially in the wake of Brexit.

Casual derogatory comments by politicians about foreigners, migrants, and refugees before, during and after the Brexit vote on 23 June 2016 was interpreted by some to legitimise overt racism and xenophobia.

At its peak following the referendum, reporting of hate crime in England, Wales and Northern Ireland increased by 58% over the previous year according to the National Police Chief’s Council.

The United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination expressed deep concern that the referendum campaign was marked by divisive, anti-immigrant and xenophobic rhetoric, and that many politicians and prominent political figures not only failed to condemn it, but also created and entrenched prejudices, thereby emboldening individuals to carry out acts of intimidation and hate towards ethnic or ethno-religious minority communities and people who are visibly and audibly different.

On 16 June 2016, Labour MP Jo Cox was shot dead outside her constituency surgery by a man whom witnesses said shouted ‘Britain first’ or ‘Put Britain first’.

In September 2016, the Equality and Human Rights Commission in Scotland welcomed a report from the Independent Advisory Group on Hate Crime, Prejudice and Community Cohesion which found that too many hate crime offenders feel they have a license to offend because no one challenges them.

Less well known are the alarming statistics on hate crime against other sections of the population. In the year preceding the 80-year anniversary of the Battle of Cable Street the sharpest increase in hate crime was against those with disability: a 117.1% leap (from 228 to 495). In the same period disability hate crime incidents rose 137.7% (from 228 to 542). This period coincided with a concerted attack by the government to reduce welfare benefits for the disabled.

In addition, in the three month period after the referendum hate crimes against lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people increased 147% according to a report by Galop.

The East End today

Cable Street runs through the borough of Tower Hamlets. According to the 2011 census, the largest ethnic group in Tower Hamlets is Bangladeshi (32%), with a sizeable Black population (7%). The Jewish community has dispersed, absorbed into the fabric of society as successive waves of migrants have done in this land in the past: Vikings, Danes, Saxons, Normans, Arabs, Muslims, manual labourers, eastern Europeans, Irish, Germans, Protestants, skilled labourers, Portuguese, Scots, refugees, French, those with disabilities, financiers, Americans, composers, Africans, Chinese, athletes, Indians, Pakistanis, Ugandans, Koreans, researchers, Japanese, Greeks, philosophers, Welsh, surgeons, Italians, porters, Russians, tailors, Israelis, Australians, sailors…the list goes on.

The 80-year commemorative Battle of Cable Street march started from Altab Ali Park, named after the Bangladeshi-born resident of the East End murdered by three teenagers on 4 May 1978 in a racist attack as he walked home after work. The murder occurred during a period of heightened racial tensions in Britain stoked largely by the far right, especially the National Front – a whites-only political party committed to whites-only immigration, and forced repatriation. The killing was the catalyst for political mobilisation among the Bangladeshi community.

Now, the MP for the local East End districts of Bethnal Green and Bow is Rushanara Ali, born in Bangladesh, and a graduate of Oxford University. The Mayor of the City is Sadiq Khan, son of Pakistani immigrants.

Solidarity

So, it was through long personal commitment to challenging abuses of power that I joined hundreds to march on 9 October 2016 in commemoration of the 80-year anniversary of the Battle of Cable Street and to show solidarity with those vulnerable within our midst to threats and intimidation.

The march and rally included over a dozen unions, community organizations, activist groups, and politicians, together with hundreds of individuals. Frances O’Grady (General Secretary, TUC), Mick Cash (RMT), Sarah Sackman (Jewish Labour Movement), Nasir Uddin (East End Together), and Liz Payne (Communist Party) were among the speakers.

John Biggs, Mayor of Tower Hamlets, said, “The Battle of Cable Street was a major, major event in the history of East London, but I think it’s a major event in the history of our country as well.”

He added: “When, in 1936, people came and they threatened us with violence and division, ordinary people […] came out of their homes and said ‘we’re not going to put up with this: we’re not going to have our community torn apart by people who don’t care for us, just want to tear us to pieces, just want to cause violence, just want to label people’.”

Jeremy Corbyn, leader of the Labour Party, addressed the rally and spoke of its personal significance: “A mile away from where we stand today stood a young woman alongside thousands of local people, trade unionists, socialists, communists, Christians, Jews, Muslims, people of all and no faith. They stood here, and, it was told to me in great detail, with one simple aim: to stop Mosley and his fascists marching through the East End”. He added, “That woman was my mother”.

Many of the speakers referred to increasing racism post-Brexit. Roger Mackenzie of UNISON said that “people feel confidence about their racism right now”.

Matt Wrack, General Secretary of the Fire Brigades Union added that the battle against fascism that Cable Street represented was also won “by undermining any support they had by campaigning on issues that affected all sorts of people from whatever background, particularly on housing”.

Conclusion

Standing up to power may come with some cost but standing by never stops abuse. Those who bully and intimidate exploit fear and cowardice.

After 1932, fascism took hold across continental Europe. It did not prosper in Britain. The stand against Mosley’s Blackshirts put an end to that. The Battle of Cable Street helped keep their hate, intolerance and intimidation at bay; in time solidifying as a collective story of successful anti-fascist resistance. But such hatred, intolerance and intimidation can too easily recur, so – as another Irish lawyer once said – the condition of liberty is eternal vigilance.

.

Further resources

News reel footage of the Battle of Cable Street, 1936: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-AQDOjQGZuA

Online account of the Battle of Cable Street, with illustrative archival videos and documentary materials: http://www.cablestreet.uk/

.

References to a selection of my previous equality and anti-discrimination work

Feenan et al. (2016) ‘Life, Work and Capital’, International Journal of the Legal Profession 32(1):1-12.

Feenan (2016) ‘Measures of Diversity’, SLSA Blog, 15 June.

Feenan (2009) ‘Editorial Introduction – Women and Judging’, Special issue of 5 papers on ‘Women and Judging’ commissioned by the journal Feminist Legal Studies 17(1): 1-9.

Feenan (2008) ‘Women Judges: Gendering Justice, Justifying Diversity’, Journal of Law & Society 35(4): 490-519.

Feenan (2007) ‘Understanding Disadvantage Partly through an Epistemology of Ignorance’, Social & Legal Studies 16(4): 509-531.

Feenan (2006) ‘Religious Vilification Laws: Quelling Fires of Hatred?’ Alternative Law Journal 31(3): 153-158.

Feenan (2005) Applications by Women for Silk and Judicial Office, A Report Commissioned by the Commissioner for Judicial Appointments for Northern Ireland.

Feenan (2002) ‘Defining Sexual Orientation’, Irish Law Times 20: 278.

Feenan (2002) ‘Out-Right Reform’, Frontline: Social Welfare Law Quarterly 44: 12-13.

Feenan et al. (2001) Enhancing the Rights of Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual People in Northern Ireland. Belfast, Northern Ireland Human Rights Commission.

Feenan (1998) ‘Featuring Gender in a Northern Ireland Newspaper’, Irish Journal of Feminist Studies 3(1): 16-25.

.

Acknowledgement

Thanks, as always, to Karen Bensusan for her love, support, and assistance.

.

© Dermot Feenan 2016