15-minute read

Dermot Feenan

LLB MA LLM Barrister-at-Law (non-practising) FRSA

.

Introduction

The process of appointments to public bodies has received increasing attention over the last three decades in the United Kingdom. Concern about who gets appointed led to the creation in 1995 of the Office of Commissioner for Public Appointments (with similar but separate offices subsequently created for regulation of certain public appointments in Scotland and in Northern Ireland). The process of appointment to public bodies raises broad constitutional issues concerning the appropriate balance of power between the elected government through its ministers and those interests which lie above and beyond the agendas of the party or coalition partners in government at a particular point in time. The composition of these non-departmental public bodies, which carry out extensive executive or regulatory functions and cumulatively handle a total budget of hundreds of billions of pounds annually, raises issues of representation, equality and, in the language of recent times, diversity and inclusion. One such issue concerns the socio-economic background of those who get appointed, those who appoint, and those who oversee the process of appointment to these bodies. Increasing attention is being paid, including in the Civil Service, to the need to ensure equality of opportunity in public life for people across socio-economic backgrounds. This is especially important in Britain, where social class distinctions and resulting inequalities continue to damage opportunities for millions of people, impairing, amongst other things, the economy, the arts, and governance.

In this short article, I set out and discuss the response of Peter Riddell CBE, Commissioner for Public Appointments, to my question – following his speech to the Constitution Unit, UCL, 29 April 2021 – as to whether his office monitors socio-economic background in public appointments, if so how, and if not whether it should do so.

In posing the question, I stated that it was made with reference to section 1 of the Equality Act 2010, which has not been implemented in England but has been extended by the parliaments of Scotland and Wales to their respective jurisdictions.

Section 1(1) of the Act provides that an authority to which the section applies must, when making decisions of a strategic nature about how to exercise its functions, have due regard to the desirability of exercising them in a way that is designed to reduce the inequalities of outcome which result from socio-economic disadvantage.

This is sometimes called the ‘socio-economic duty’. The duty has implications for public appointments.

In this article, I also add some detail to the references by Mr Riddell to Scotland and Northern Ireland. I discuss related developments in those jurisdictions, and in Wales.

In posing my question to Mr Riddell, I also stated it was made with reference to concern about what seemed to be disproportionality in recent appointments of those from a public-school background. I also discuss in the article Mr Riddell’s response in relation to this matter.

Finally, I emphasise the need to address socio-economic background, including public school background, in public appointments.

Mr Riddell’s response

Mr Riddell said that he is “absolutely committed to broadening the social background”. This resonates with the statement in his Annual Report 2019-2020 that it would be ‘desirable to have a wider social range of appointees’ (p. 10).

Mr Riddell explained that his office relies on diversity monitoring forms but monitoring “is not as detailed as you’re implying, it certainly doesn’t cover education”. He added, “we do try to cover occupation”.

It is unclear from this reply whether socio-economic background is in fact included routinely in monitoring of public appointments for which his office is responsible (which includes a number of UK-wide public bodies and specified public bodies in Wales but not appointments to public bodies in Northern Ireland and Scotland which are regulated by Commissioner for Public Appointments for Northern Ireland and the Ethical Standards Commissioner in Scotland, respectively). Mr Riddell’s reference to trying to cover occupation suggests that it is not.

Mr Riddell added, “we don’t have as much data as I would like on that”. He noted that completion of the diversity monitoring forms is currently voluntary, but that his office would like to see this become compulsory (subject to allowing for non-response to specific questions).

Mr Riddell had earlier noted in his prepared speech that the Cabinet Office is “committed to updating its Diversity Action Plan with a broader definition of diversity looking also at a range of views and social and geographical diversity.” HM Government’s current Public Appointments Diversity Action Plan 2019 does not mention social background.

The Candidate Information Pack for the vacant position of Chair of the Social Mobility Commission states that applications are welcome from candidates regardless of, amongst other grounds, ‘socio-economic background’ (p. 4). Within the early section on ‘Diversity and Equality of opportunity’ (pp. 4-5), the Pack adds: ‘The Social Mobility Commission champions social mobility in all of its policies and is committed to opening up opportunities on its Board for people from all backgrounds, all socio-economic classes and all regions of the UK’ (emphasis added) (p. 4). This competition is regulated by the Commissioner, so it is surprising that this was not mentioned in the reply.

Mr Riddell did add in response to my question that “in Scotland, they do have more extensive data than we have’.

Having mentioned the position in Scotland, Mr Riddell said: “It’s a battle between comprehensiveness and depth”. It is not clear what this means vis-à-vis the issue of monitoring socio-economic background.

In 2008, the Office of the Commissioner for Public Appointments in Scotland noted in the report Diversity Delivers that data was not collected on employment status (and sector) and income band. These are measures sometimes used for recording socio-economic status.

In his Annual Report 2019-2020, Mr Riddell notes the use of those measures – following his observation that ‘it will be important to have clear-cut and widely accepted metrics so everyone can see what progress is being made’ (p. 10).

It is perhaps instructive here to set out in more detail how socio-economic background has been addressed in relation to public appointments in Scotland.

Scotland

The Diversity Delivers report recommended that monitoring of employment status (and sector) and income band take place within 3 years and that within 4-5 years there should be statistical analysis of information from monitoring forms to identify applicant trends.

That report also recommended: ‘If there are sections of the population where application numbers and progress through the system are not improving, investigate and consider positive action’ (p. 17).

The report set out an ambition in such monitoring ‘to provide baseline statistics against which to set aspirational targets’ (p. 47).

Since publication of the report (in 2008), section 1 of the Equality Act 2010 has – as I mentioned in my question to Mr Riddell – been extended to Scotland.

Section 1 of the Act was extended, in relevant part, to Scotland by The Equality Act 2010 (Commencement No. 13) (Scotland) Order 2017 and The Equality Act 2010 (Authorities subject to the Socio-economic Inequality Duty) (Scotland) Regulations 2018.

Ministers must comply with section 1(1) of the Equality Act 2010 in relation to public appointments.

The Ethical Standards Commissioner (which replaced the Commissioner for Public Appointments in Scotland) regulates and monitors many public appointments in Scotland.

The Ethical Standards Commissioner’s Annual Report 2019-2020 includes for the first time in one of the Commissioner’s annual reports data on applicants’ household income and the sector in which they work.

The Commissioner also records in that report meeting in 2019 with the Cabinet Secretary for Finance, Economy and Fair Work (with overall responsibility for public appointments), who expressed a commitment to broader diversity, including socio-economic diversity on boards.

The Annual Report 2019-2020 notes that ‘those whose household income is in the top 5% of the population apply in disproportionately greater numbers than others and are invariably more successful when they do so.’ (p. 4)

Those in the top two (of nine) income bands make up the majority of applicants for public bodies. Those in the highest band are almost three times more likely to apply than those in the median band for income in Scotland, and are ten times more likely to be appointed.

The Commissioner also noted intersectional connections between characteristics such as disability and household income.

The Ethical Standards Commissioner reported on analysis of the views of applicants in 2019, the first time such research had been conducted. The report stated: ‘Respondents have consistently found the application pack to be clear and helpful over the past four years’ (p. 12).

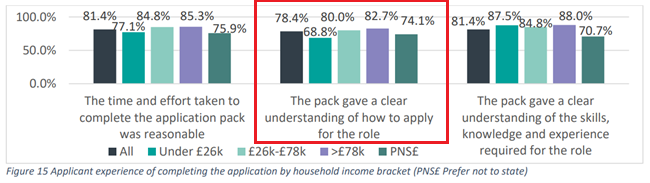

Yet, an unremarked upon fact is that applicants from lower income bands were less likely to find that the applicant pack gave a clear understanding of how to apply for the role. Those in the lowest income band were 14% less likely to find the pack clear than those in the highest band (see bar chart, below, bordered in red).

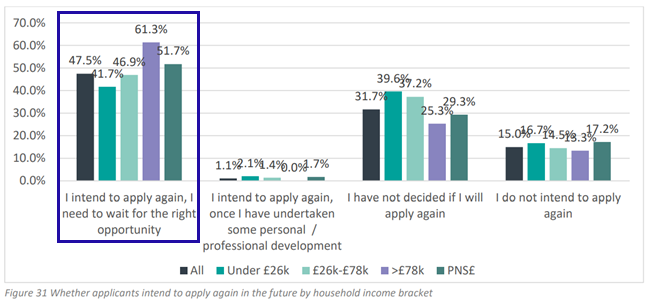

Similar, but more pronounced, data pertained to levels of confidence among applicants in wishing to apply again in future. Applicants in the highest income band were 32% more likely than those from the lowest income band to intend to apply again (see bar chart, below, bordered in blue).

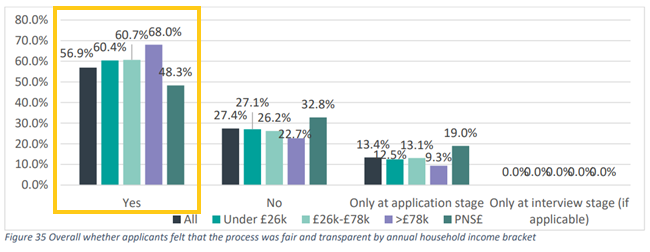

Again, those in the highest income band are more likely (by 10%) than those in the lower income bands to believe that the application process was fair and transparent (see bar chart, below, bordered in gold).

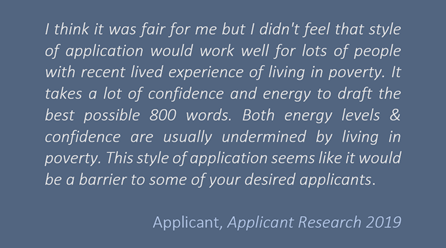

One of the applicants was quoted in the report, explaining that the style of application would be a barrier to those with recent experience of living in poverty.

The foregoing data show that a range of socio-economic factors, such as annual household income, can affect a public appointments process – and sometimes this can be a significant effect.

The Scottish Government responded to the research by stating in May 2021 that it ‘will investigate how to increase applications from people from lower income households. This will start with improving the way that socio-economic background and status is monitored within a new applicant tracking system.’ (p. 2)

The Ethical Standards Commissioner had, in the interim, conducted a survey on time commitment, remuneration and other aspects of the role of public appointees. The survey in 2020 included the following question: “The Commissioner is concerned that the current levels of time commitment and remuneration may be precluding applications from and appointments to currently under-reflected groups such as disabled people, people under 50, people from a BME background and people with lower than average household incomes. Do you have any views on this and/or ideas about what should be done to increase board diversity?” (p. 24).

In addition, in August 2020, the Ethical Standards Commissioner conducted a consultation on potential revisions to the Code of Practice for Ministerial Appointments to Public Bodies in Scotland. The first question in the consultation questionnaire was: ‘Should the Code have clear and specific provisions about the measures that the Scottish Ministers should adopt when planning to appoint new members in respect of diversity and should diversity be expanded to include other factors such as household income, sector worked in and skills, knowledge and experience?’ (p. 5).

The foregoing detail adds flesh to Mr Riddell’s reference to Scotland, underscoring the noteworthy developments in public appointments with reference to socio-economic background in that jurisdiction.

Northern Ireland

Mr Riddell also referred in his reply to a scheme in Northern Ireland: ‘Boardroom Apprentice’, which, he said, “does try to broaden the social range of people and has mentoring schemes and has resulted in people having public appointments in Northern Ireland.” “I’m very keen to do that”, he added.

The Commissioner’s website refers to the Boardroom Apprentice scheme, linking to the document ‘BOARDROOM APPRENTICE’. The document does not refer specifically to socio-economic background. Instead, it refers to ‘all ages, backgrounds and abilities’ and mentions applications with reference to gender, sexual orientation, disability, and ethnic minority status (below).

It would be helpful to obtain from the Boardroom Apprentice scheme further information on what is meant by ‘background’, particularly with reference to socio-economic status.

I served as an Independent Assessor to the Office of the Commissioner for Public Appointments for Northern Ireland for almost three years, spring 2013 through early 2016, and have monitored the Office’s work since then. I am not aware of any policy that addresses socio-economic background in public appointments in Northern Ireland.

A former Commissioner for Public Appointments for Northern Ireland, John Keanie, referred to social background in relation to public appointments in one of his reports – though in an oblique way.

In Under-representation and lack of diversity in Public Appointments in Northern Ireland, 2014, he noted that gender, age, disability and minority ethnic status were being monitored for public appointments, and added:

There is much anecdotal evidence, from business organisations and individuals, and from third sector organisations and individuals, that people from these backgrounds, particularly younger people with modern skills and perspectives, and people who have gained a deep knowledge of social and economic challenges from their work in communities, are under-represented and are reluctant to submit themselves to a recruitment process that they see as ‘not for them’. (p. 7)

He also reported on research by the Government Equalities Office which found that one of the reasons why there were so few women and other under-represented groups on public and private sector boards was that ‘diverse candidates lack social capital and are often excluded from influential social networks, affecting access to boards. In addition, boardroom cultures can be inhospitable to individuals from under-represented groups.’ (p. 9)

I sought to ensure in those appointments in which I was involved as an Independent Assessor that consideration was given, when appropriate, to the need for diversity with reference to socio-economic background.

The last five reports from the Commissioner, now Judena Leslie, for the years 2015/2016 through 2019/2020 make no mention of socio-economic background. The Commissioner’s Business Plan for 2020-2021 does not refer to socio-economic background. The commitment to diversity is largely focused on gender. The report sets as an objective, to ‘promote diversity in public appointments in particular to promote the Executive targets for gender equality at Board member and Board chair levels’ (p. 15).

This lack of commitment to socio-economic background is unfortunate, not least as the Cabinet Office’s Governance Code on Public Appointments (December 2016) states: ‘Diversity should be considered in its broadest sense and go beyond gender, disability or race, to include wider characteristics such as sexual orientation, gender identity and social background’ (fn. 6, emphasis added).

Initiatives in Wales towards addressing socio-economic background are more promising.

Wales

The Senedd recently extended s. 1 of the Equality Act 2010 to Wales.

The legislation which implemented s. 1 in Wales is the Equality Act 2010 (Commencement No. 15) (Wales) Order 2021, with the public authorities to which the duty applies set out in the Equality Act 2010 (Authorities subject to a duty regarding Socio-economic Inequalities) (Wales) Regulations 2021. The Regulations extend the duty to the Welsh Ministers. Those ministers have responsibility for appointments to a range of public bodies in Wales. The ministers must therefore comply with section 1(1) of the Equality Act 2010 in relation to these appointments.

A flavour of the approach of the Welsh Government to socio-economic background and public appointments is provided in its Action Plan: Year 1: 2020-2021, Diversity and Inclusion Strategy for Public Appointments in Wales, which includes the following data-gathering goal: ‘Set up a robust system for collecting data on different protected groups on Boards; include socio-economic grouping, language ability, and geographical location’ (p. 2). This goal includes agreeing ‘proxy indicators for socio-economic groups, and use for data collection in the future’ (p. 3).

The Action Plan commits the government, ‘[a]s data are improved […] to consult and if desired set overall targets across all Boards in Wales for BAME, disabled, LGBT+ and young people and socioeconomic groups, recognising that individual Boards have varying specific requirements’ (p. 4).

In a report of a roundtable on providing better support for ‘near miss’ and potential candidates in underrepresented groups to apply successfully for public appointments in Wales, the authors refer to one model of support: Beyond Suffrage – which supports women of colour aged 18-30 to become trustees in the voluntary sector.

The authors of the report refer to ‘[a] challenge the organisation has faced is to ensure that the programme does not enable or exacerbate inequality. In the first cohort, the majority of women were from a middle-income background, highlighting the importance of reaching out to women from working-class backgrounds who may be in greater need of support’ (p. 14). It is a rare reference to social class among the numerous reports on public appointments in the UK.

The Action Plan adds that the Public Appointments Team should ‘identify robust data for Ministers to make decisions and go out to consult, for targets for all protected groups, and for under-represented socio-economic groups’ (p. 19).

The extension of s. 1(1) of the Equality Act 2010 to Wales and the approach of the Welsh government in its Action Plan to socio-economic data sets up a challenge for the Commissioner. He is required to regulate 55 public bodies in Wales. The Commissioner must consider how his functions address the requirements being made by the Welsh government in relation to socio-economic status and public appointments in Wales.

It is obvious from the official approaches to socio-economic background and public appointments in Scotland and Wales that there is a focus on very specific socio-economic measures such as income band, with a fleeting reference in Wales also to social class. Little or no attention has been given, however, to public school (i.e. independent/ fee-paying school) background.

The Irish Human Rights and Equality Commission has recently established that the definition of socio-economic status is best developed by listing key practical and identifiable features of difference across social classes, suggesting five indicators including educational background:

- Family background such as inter-generational history of occupation

- Geographical location such as living in areas of relatively high concentrations of socio-economic disadvantage

- House tenure or home ownership

- Educational background

- Economic situation.

The Minister for Children, Equality, Disability, Integration, and Youth in Ireland, Roderic O’Gorman, has committed to an examination of Ireland’s Equality legislation within the next year, with a public consultation on the introduction of a ‘disadvantaged socio-economic status’ ground before 2022.

As a northern Irish person not from a public-school background who has lived in southern England continuously for almost seven years and worked for part of this time as a researcher and lecturer within higher education, it is impossible not to be struck by the significance of public-school background in perpetuating inequality in the country and, in particular, how this is associated with the closing off of opportunities to the majority of the population, including extremely talented individuals. That significance is also well-documented by others, including:

- scholars (such as David Kynaston and Francis Green, Aaron Reeves and colleagues and Sam Friedman and Daniel Laurison),

- charities (such as The Sutton Trust),

- groups (such as the Private Education Policy Forum),

- political organisations (such as Labour Against Private Schools), and

- the advisory non-departmental public body The Social Mobility Commission.

Such has been my concern with the current government’s position on equality that when a colleague recently suggested that I apply for one of the two lay vacancies on the Committee on Standards in Public Life, I concluded that it was unlikely that someone from my background would be considered appointable and decided not to apply. It is partly against this context that I asked my question to the Commissioner, and decided to do so publicly.

Public school background

I noted in my question to Mr Riddell that it was made also with reference to the apparent disproportionality in the numbers of those from a public-school background in recent public appointment competitions.

Mr Riddell replied, “I don’t know about this public school point…and all that…at all”. This is concerning, even setting aside what might be perceived as a casual, dismissive remark ‘and all that…at all’. Cursory examination of appointments recently to high profile public bodies shows significant prevalence of appointees from public school backgrounds.

The four recent appointments to the Equality and Human Rights Commission, for example, are all public school educated (with half going on to Oxbridge).

- Jessica Butcher: King Edward School (then Oxford)

- David Goodhart: Eton

- Su-Mei Thompson: Cheltenham Ladies College (then Cambridge)

- Lord Ribeiro: Dean Close School.

These particular appointments attracted considerable concern in the media. Shortly afterwards, on 1 April 2021, Lord Wharton was appointed Chair of the Office for Students Board. He, too, was privately educated. In the same month it was announced that Shelagh Legrave OBE DL had been appointed as a Lay Further Education Commissioner. She, too, had been privately educated. At the start of the year, the Home Secretary announced the appointment of Lord Herbert of South Downs as the new Chair of the College of Policing. He was also educated at public school, Haileybury (where the fees for senior boarding are currently £36,144 per annum – £6,154 above the median household disposable income of £29,990 in the UK in 2020). At least two of the four appointments to the Board of the Victoria and Albert Museum in 2020 went to public school (Amanda Levete and Amanda Spielman, both educated at the independent fee-paying school St Paul’s School for Girls, where the fees for a year for a new entrant to Senior Year are currently £27,831). Comprehensive monitoring of candidates’ (and panel members’) educational background will help better assess the prevalence of public-school background in public appointments.

In addition to these appointments, it is known that 45% of the chairs of public bodies are independently educated.

Concerns about the disproportionality of public school background in positions of influence in Britain is well-documented, including most recently in the report Elitist Britain 2019: The educational backgrounds of Britain’s leading people by the Sutton Trust and Social Mobility Commission. Concerns range across appointments, including to Cabinet, the judiciary, and journalism.

In 2018, the Civil Service published Measuring Socio-economic Background in your Workforce: recommended measures for use by employers. The report recommended that the type of school attended should be a measure alongside other measures to be commonly used by employers in monitoring diversity in the workforce, including the Civil Service. In 2020, the Social Mobility Commission produced Socio-economic diversity and inclusion, a toolkit in order to help attract and develop employees from all socio-economic backgrounds.

The reasons for concern about the disproportionality of those from public school backgrounds in public appointments are similar across those other sectors: under-representation; inequality, including inequality of opportunity; and, given that most public school pupils come from affluent, middle-/upper-class backgrounds, the narrowing of the range of life experiences needed in decision making in public affairs.

While it is not the role of the Commissioner to comment on the merit of individual appointees, the Commissioner must, by law, exercise his functions with the object of ensuring that appointing authorities act in accordance with the Governance Code on Public Appointments, including the principles of public appointments.

The Governance Code on Public Appointments sets out a list of ‘Principles of Public Appointments’. One of the ‘Principles of Public Appointments’ is ‘Diversity’. It states: ‘Public appointments should reflect the diversity of the society in which we live and appointments should be made taking account of the need to appoint boards which include a balance of skills and backgrounds.’ As has already been noted, the Code adds: ‘Diversity should be considered in its broadest sense and go beyond gender, disability or race, to include wider characteristics such as sexual orientation, gender identity and social background.’

In addition, one of the Seven Principles of Public Life (sometimes called the ‘Nolan’ principles after Lord Nolan, who produced the principles) is objectivity. This states: ‘Holders of public office must act and take decisions impartially, fairly and on merit, using the best evidence and without discrimination or bias.’ This must entail at a minimum that discrimination or bias does not affect the public appointments process. The principles are silent on the grounds of discrimination or bias. They should include the nine protected characteristics set out in the Equality Act 2010. While socio-economic background is not one of those characteristics, this does not mean that this ground should thereby be dismissed for the purpose of non-discrimination.

There are persuasive reasons why discrimination or bias should not be permitted on the basis of socio-economic background. These include the fact that Parliament intended in passing s. 1 of the Equality Act 2010 that inequality of outcome with reference to socio-economic background should be addressed (even if the UK government has not yet implemented the section in England).

There is increasing recognition in other jurisdictions of the need to protect against such discrimination. More broadly, ‘social origin’ is a ground for non-discrimination in Article 14 of the European Convention of Human Rights.

The inclusion of social status as a basis for protection against discrimination has been achieved elsewhere. A number of jurisdictions in Canada, including New Brunswick and the North West Territories, protect against discrimination on the basis of ‘social condition’ including ‘level of education’. In the North West Territories, the Human Rights Act provides: ‘”social condition”, in respect of an individual, means the condition of inclusion of the individual, other than on a temporary basis, in a socially identifiable group that suffers from social or economic disadvantage resulting from poverty, source of income, illiteracy, level of education or any other similar circumstance’.

The Commissioner also has the power, conferred by law, to conduct an investigation into any aspect of public appointments ‘with the object of improving their quality’ and may conduct an inquiry into the procedures and practices followed by an appointing authority in relation to any such appointment whether in response to a complaint or otherwise.

The apparent disproportionality in the number of appointees from public school backgrounds in some recent appointments could plausibly be consistent with similar recent appointments in Cabinet. Of the 27 ministers attending Cabinet, 19 (70%) received a private education compared with just 7% of the general population. This is ten times the proportion of the general public who go to fee-paying schools.

Boris Johnson is perhaps an example par excellence of someone from a public-school background: educated at Ashdown House, a preparatory boarding school, and Eton.

The proportion of those from public school backgrounds in Johnson’s current Cabinet is more than double the proportion in Theresa May’s Cabinet in 2016 (at 30%).

This trend in public-school appointments is plausibly consistent with the concerns expressed by Mr Riddell in his speech about ‘the breadth of the campaign’ by the present government to ‘appoint allies to the boards of public bodies’. Mr Riddell noted that some ministers ‘are now seeking to tilt the process even further to their advantage’. He referred to ‘leaks that Number 10 favours certain candidates even before a competition starts’. In addition, he noted that ‘ministers have tried to undermine the independence of interview panels’. This has included, he said, ‘cases of ministers trying to appoint SIPMs [Senior Independent Panel Members] such as Conservative peers who clearly breach this rule.’ He added that ‘there have been cases of ministers seeking to pack interview panels’.

It might seem remarkable to some that the issue of socio-economic background has not received as much attention in England as it has in Scotland and Wales. Over 25 years ago, John Viney and Judith Osborne noted in Modernising Public Appointments concerns about ‘a new magistracy, croneyism [sic] and endemic political bias’ in public appointments. They stated that ‘the current – broadly unrepresentative – composition of public appointees is the product of a system reliant upon networking’ (p. 15). ‘In Britain’, they wrote, ‘the most obvious form of networking has been the ‘old boy’ network encompassing largely public school alumni’ (p. 14).

Arguably, it is precisely the preservation of social class privilege in political power in England which continues to explain the unwillingness of certain individuals and institutions to challenge inequality with reference to socio-economic background.

Sir John Major, former Prime Minister, stated in 2013 that the dominance of a private-school educated elite and affluent middle classes in the “upper echelons” of public life in Britain was “truly shocking”. Theresa May said at the Conservative Party conference in 2016: “Too often the people who are supposed to hold big business accountable are drawn from the same, narrow social and professional circles as the executive team.”

Such dominance has been documented for a considerable period.

In the 2002-2003 parliamentary session, the Public Administration Select Committee noted in its report Government By Appointment: Opening Up The Patronage State that in ‘the debate about diversity the Government has been judged largely by its success in raising the proportions of women, people from ethnic minorities and people with a disability on public bodies to the proportions of these groups in the population at large’. The Committee added: ‘Our concerns range even wider, especially in relation to the representation of social class on public bodies’ (para. 113).

Michael Pinto-Duschinsky and Lynne Middleton recommended in their report Reforming Public Appointments for Policy Exchange in 2013 that diversity must include socio-economic diversity. The authors also recommended that the Government’s Equalities Office should widen its remit to include special initiatives to promote access to public appointments for socio-economically disadvantaged groups.

On 20 May 2021, the Civil Service announced an action plan to increase socio-economic diversity in the Civil Service. There have also been significant developments in seeking to redress socio-economic disadvantage outside the public sector. The Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy and HM Treasury have, with the assistance of the City of London Corporation, set up a taskforce to boost socio-economic diversity in UK financial and professional services.

It is worth recalling that the Office of Commissioner for Public Appointments was created in 1995 following the recommendation in Standards in Public Life: First Report of the Committee on Standards in Public Life, under the chairmanship of Lord Nolan, for an independent public appointments commissioner. This recommendation was based largely on what the report referred to as ‘public concern’ about appointments to public bodies, and a ‘widespread belief that these are not always made on merit’ (p. 6). The report also recommended that selection on merit should take account of the need to appoint boards which include a balance of skills and backgrounds.

Lord Nolan (educated at Ampleforth College, where currently advertised boarding and tuition fees are £36,486 per annum – £6,496 greater than the median household disposable income of £29,990 in the UK in 2020), did not address the matter of public school background in his examination of public appointments.

The Commissioner regulates appointments to over 300 public bodies, responsible for – as Mr Riddell noted in his speech – ‘running, regulating or advising on large swathes of British life – from national museums and galleries via prisons, charities, social mobility and human rights to scientific research and the NHS’. Latest data (for 2019) indicate that gross resource expenditure on these public bodies was £206 billion.

It will be interesting to see how Mr Riddell (educated at Dulwich College, London, where the currently advertised annual fee for full boarders is £45,234 per annum – £15,244 greater than the median household disposable income of £29,990 in the UK in 2020) will take forward his commitment to broadening social background in relation to public appointments. In order to help, I have written to Mr Riddell to encourage him to do so and to suggest that it would be helpful if he could state publicly how his office will take forward this commitment. (Copy of letter, redacted to protect personal data, below.)

Conclusion

Monitoring of socio-economic background in public appointments is weak in England, though the Commissioner for Public Appointments has stated in relation to public appointments his commitment to broadening social background. Recognition of the need for such monitoring finds strongest acknowledgement in Scotland, with monitoring of, and reporting on, income and sector background of applicants. There has been a commitment in Wales to gathering socio-economic data in relation to appointments to boards, with some research on appointments referring to social class.

It is encouraging to hear the Commissioner for Public Appointments state that he is “absolutely committed to broadening social background”. While it may be unfair to draw definitive conclusions from extemporaneous responses to broad questions during an online Q&A after a prepared speech, especially where such format does not easily provide an opportunity for the person posing the question to seek clarification to a response, a number of the Commissioner’s responses were unclear, such as the statement about ‘the battle between comprehensiveness and depth’ and whether socio-economic background is in fact included routinely in monitoring. No mention was made of significant positions taken by the Civil Service and Social Mobility Commission on socio-economic background. Nor was it noted that the Governance Code on Public Appointments specifically refers to ‘social background’.

There is a momentum in other jurisdictions towards protecting against discrimination on the basis of socio-economic background, some of which protections refer to education. There is some concern in England about the proportion of appointees from an independent, fee-paying school background in some recent appointments to public bodies given the number of the population who attend such schools. This concern about disproportionality arguably resonates with broader concerns by the Commissioner about some recent public appointments. I support comprehensive monitoring of socio-economic background, including with reference to type of school attended, in public appointments to help address these concerns.

It is to be hoped that the Commissioner will, in meeting his commitment to broadening social background, reflect further on these matters and state publicly how he will take forward the commitment.

This article is intended to record both a number of developments in seeking to eliminate socio-economic disadvantage and the commitment by the Commissioner for Public Appointments to broadening social background in relation to public appointments, and, thus, to provide a reference point by which progress may be monitored and assessed.

.

Amended, 28 May 2021, to correct typos and to remove an unclear reference to ‘action’ (in the first sentence of para. 2 in the Conclusion) and to substitute ‘take forward’ in the final paragraph of the section ‘Public school background’ to clarify the sense of forward-looking commitment.

.

© Dermot Feenan 2021

________________________________________

The full speech by Peter Riddell (with the Q&A) is available via podcast and by video. The text of the speech is also available on the website of the Commissioner for Public Appointments, here.

The Commissioner responded in full to the article, and accompanying letter, by letter dated 28 May 2021, published here on the Commissioner’s website.